2019

"Extreme Job", "Parasite", "Forbidden Dream", "The Gangster, the Cop and the Devil"

Despite opening the year with the massive hit comedy Extreme Job, which racked up the second highest number of admissions in Korean cinema history, things were not looking good for the film industry as a whole at the start of 2019. An unprecedented string of big-budget box office failures in 2018 had rattled the nerves of investors, and suggested that the big studios were beginning to lose touch with audience tastes. Although viewers had not turned their backs on Korean film entirely (the success of Extreme Job was proof of that), an overall sense of frustration was palpable among audience members in online forums and review sites.

As for the big-name auteurs, only one was scheduled to release a new film in 2019: Bong Joon Ho with his dark social drama Parasite. Selected for the competition section at Cannes, the film features an ensemble cast headed by Song Kang-ho and looked poised to leave a big impression both domestically and internationally. Also stirring up anticipation was the period drama Forbidden Dream by director Hur Jin-ho, featuring the veteran stars Choi Min-sik and Han Suk-kyu. A release is expected in the second half of the year.

Korean independent film, meanwhile, continues to struggle, with a promised boost in government support yet to materialize. Although large numbers of independent films continue to be made, often at great personal sacrifice, the challenge of finding an audience for these works grows more and more difficult by the year. (Written on May 8)

Reviewed below: Innocent Witness (Feb 13) - Svaha: The Sixth Finger (Feb 20) - Birthday (Apr 3) - 0.0MHz (May 29) - Exit (Jul 31) - The Divine Fury (Jul 31) - Warning: Do Not Play (Aug 15) - The House of Us (Aug 22) - House of Hummingbird (Aug 29) - Crazy Romance (Oct 2) - Vertigo (Oct 16) - Kim Ji-young, Born 1982 (Oct 23).

| Korean Films | Admissions | Release | Revenue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Extreme Job | 16,265,618 | Jan 23 | 139.7bn |

| 2 | Parasite | 10,313,086* | May 30 | 87.5bn |

| 3 | Exit | 9,426,011 | Jul 31 | 79.2bn | 4 | Ashfall | 8,252,669* | Dec 19 | 70.0bn |

| 5 | The Battle: Roar to Victory | 4,787,538 | Aug 7 | 40.6bn |

| 6 | The Bad Guys: Reign of Chaos | 4,573,371 | Sep 11 | 39.6bn |

| 7 | Kim Ji-young, Born 1982 | 3,678,156 | Oct 23 | 30.3bn |

| 8 | Money | 3,389,125 | Mar 20 | 28.9bn |

| 9 | The Gangster, The Cop, The Devil | 3,364,712 | May 15 | 29.1bn |

| 10 | Start-Up | 3,317,038* | Dec 18 | 28.1bn |

| All Films | Nationwide | Release | Revenue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Extreme Job (Korea) | 16,265,618 | Jan 23 | 139.7bn |

| 2 | Avengers: Endgame (US) | 13,934,592 | Apr 24 | 122.2bn |

| 3 | Frozen 2 (US) | 13,747,792* | Nov 21 | 114.8bn |

| 4 | Aladdin (US) | 12,552,213 | May 23 | 107.0bn |

| 5 | Parasite (Korea) | 10,313,086* | May 30 | 87.5bn |

| 6 | Exit (Korea) | 9,426,011 | Jul 31 | 79.2bn |

| 7 | Ashfall (Korea) | 8,252,669* | Dec 19 | 70.0bn |

| 8 | Spider-Man: Far From Home (US) | 8,021,145 | Jul 2 | 69.0bn |

| 9 | Captain Marvel (US) | 5,802,811 | Mar 6 | 51.5bn |

| 10 | Joker (US) | 5,247,363 | Oct 2 | 45.4bn |

* Includes admissions from 2020. Revenue is in Korean currency (US$1=~1200 won).

Source: Korean Film Council (www.kobis.or.kr).

Seoul population: 9.8 million

Nationwide population: 51.8 million

Soon-ho (Jung Woo-sung, Steel Rain) is a lawyer who, in the early part of his career, established his reputation working for a progressive legal association. After years of defending ordinary citizens against large corporations, he has decided to accept a well-paid job at a leading firm. His new boss admires his talent and skill, but is concerned that Soon-ho's squeaky-clean image will make his rich corporate clients uncomfortable. "You need to get some dirt on you," the boss suggests. Meanwhile outside of work, Soon-ho leads a quiet life with his elderly father, who has Parkinson's disease. The one close friend he has is a former colleague at the legal association who is raising a school-aged daughter. But now that Soon-ho has, in effect, gone over to "the other side," she no longer feels as comfortable with him, either.

Soon-ho's first major case at his new job is one that the firm takes on for the sake of its image, rather than a big payoff. A housekeeper has been accused of murdering her employer, but she insists that she was simply unsuccessful in preventing a suicide. It seems like a straightforward case, but with one complication: the incident was witnessed by a school-aged autistic girl (Kim Hyang-gi, Along With the Gods) who lives in the same neighborhood. The girl, obviously traumatized by what she has seen, has given a statement to the police that supports the murder charge. But she refuses to meet with Soon-ho. Hoping to find some way to discredit her testimony, he starts coming to her school each day at the time she gets off, and walking home with her.

Soon-ho's first major case at his new job is one that the firm takes on for the sake of its image, rather than a big payoff. A housekeeper has been accused of murdering her employer, but she insists that she was simply unsuccessful in preventing a suicide. It seems like a straightforward case, but with one complication: the incident was witnessed by a school-aged autistic girl (Kim Hyang-gi, Along With the Gods) who lives in the same neighborhood. The girl, obviously traumatized by what she has seen, has given a statement to the police that supports the murder charge. But she refuses to meet with Soon-ho. Hoping to find some way to discredit her testimony, he starts coming to her school each day at the time she gets off, and walking home with her.

Innocent Witness could easily have been a forgettable, or even a very bad film. In recent years a number of Korean movies have depicted autistic characters, but not all of them have handled these depictions with sensitivity. In addition, the setup and overall plot structure of this film looks suspiciously predictable. In the hands of another director, it might have been a chore to sit through.

But one thing that director Lee Han has clearly demonstrated over the course of his career is that he is a gifted storyteller. Beginning with his breakout hit Punch (2011), he has specialized in works that are centered around well-drawn, three-dimensional characters while also gently introducing a contemporary social issue, like multiculturalism or (in the case of his well-reviewed low-budget drama Thread of Lies) teen suicide. His most recent work before Innocent Witness was the ambitious A Melody to Remember (winner of the Audience Award at the 18th Udine Far East Film Festival), which is based on a true story about a children's choir formed during the Korean War.

More than anything, Innocent Witness succeeds because of its memorable, well-drawn characters. Jung Woo-sung's Soon-ho comes across as much more than simply a lawyer torn between idealism and material success. He has a natural generosity of spirit that, in a very human way, can sometimes cross into overconfidence, leading him to overreach or say the wrong thing. His rival attorney in the case, played by Lee Kyu-hyung, is marked by a charismatic blend of determination, awkwardness and inexperience. And Kim Hyang-gi is convincing as the autistic Jiwoo, whose idiosyncratic means of expressing emotion masks a determined intelligence within. The end result is a film that is effortlessly comfortable to watch, respectful of the autistic character at its center, and steadily more emotional as it reaches its final act. The film's warmth, in this case, feels earned. (Darcy Paquet)

The film begins with what appears like the birth of the Anti-Christ in a rural Korean setting: in 1999, a disfigured, fur-covered creature is born as an elder twin to a pair of girls, nourishing itself on the flesh of her sister's leg while floating in her mother's womb. Their parents perish, but both children survive and grow up to become teenagers. Geum-hwa (Lee Jae-in, Horror Stories III, Our Body) and her religious-nut grandmother reluctantly have cared for her beastly sister confined in a warehouse for sixteen years (the film is set in 2015). Meanwhile, Pastor Park (Lee Jung-jae, Assassination, Along with the Gods series), a somewhat sleazy investigator of dubious religious organizations and practices, is recruited by a group of Buddhist abbots to look into a pseudo-Buddhist cult calling itself "Deer Hill." Park, partnered with his earnest assistant Joseph (David Lee, The Fortress, Swing Kids), starts investigation expecting an open-and-shut case, but he soon learns to his increasing alarm that some grandiloquently horrifying scheme has been set into motion by the cult, with the circumstantial evidence pointing to genuine supernatural presences among its members. Will the fast-talking Pastor and his naive assistant be able to unlock the mystery surrounding Deer Hill in time and save Geum-hwa, targeted by a tormented serial killer Na-han (Park Jung-min, Tinker Ticker, Psychokinesis), already responsible for murdering several young girls?

An RnK (Weyu Naegang) Production (Director Ryoo Seung-wan and his wife Producer Gang Hye-jung's company), Svaha is the sophomore film written and directed by Jang Jae-hyun, whose The Priests (2015) was one of the most enjoyable Korean horror films of recent years, a thoroughly authentic (although garnished by very welcome sprinkles of droll, knowing humor) yarn of Catholic exorcism, that took its genre conventions seriously yet cleverly localized them to generate its own distinctive flavor. The Priests was a big sleeper hit of 2015, collecting 5.4 million tickets and making horror fans (such as yours truly) sit up and take notice of its director. If anything, his follow-up film is even more ambitious and almost defiant in its willingness to immerse itself in all manners of occult arcana, including quite a handful of Buddhist mythology (the Four Deva Kings, the prophesized advent of the Maitreya Buddha, and so on). Despite lacking the surefire commercial ingredient of Jang's previous film, namely Gang Dong-won smartly decked in Catholic priest's frock, Svaha still managed to be a moderate hit during the 2019 winter season, selling approximately 2.4 million tickets, just enough to break even commercially.

An RnK (Weyu Naegang) Production (Director Ryoo Seung-wan and his wife Producer Gang Hye-jung's company), Svaha is the sophomore film written and directed by Jang Jae-hyun, whose The Priests (2015) was one of the most enjoyable Korean horror films of recent years, a thoroughly authentic (although garnished by very welcome sprinkles of droll, knowing humor) yarn of Catholic exorcism, that took its genre conventions seriously yet cleverly localized them to generate its own distinctive flavor. The Priests was a big sleeper hit of 2015, collecting 5.4 million tickets and making horror fans (such as yours truly) sit up and take notice of its director. If anything, his follow-up film is even more ambitious and almost defiant in its willingness to immerse itself in all manners of occult arcana, including quite a handful of Buddhist mythology (the Four Deva Kings, the prophesized advent of the Maitreya Buddha, and so on). Despite lacking the surefire commercial ingredient of Jang's previous film, namely Gang Dong-won smartly decked in Catholic priest's frock, Svaha still managed to be a moderate hit during the 2019 winter season, selling approximately 2.4 million tickets, just enough to break even commercially.

Svaha faithfully follows many conventions of supernatural horror-thrillers, instantly recognizable to the filmgoers of practically any nation, yet, like The Wailing, serves as an example of uniquely South Korean genre cinema. Its central conceit of an investigator of the supernatural running into a case that severely tests his rational skepticism is altogether familiar from countless films and even TV series, such as Kolchak: The Night Stalker. Yet, Svaha feels entirely fresh in its theological or metaphysical eclecticism. Throughout the film, Pastor Park accepts at face value the supernatural phenomena of the quasi-Buddhist type he confronts, but more importantly, his attitude turns out to be resolutely humanistic. Park fights against not so much against the situations that chafe against his Christian beliefs as against those characters arrogant and callous enough to engineer sacrifices of "little people" for what they believe to be a grand divine purpose. What is interesting is that the heterogeneity of cosmological schemata (karmic destiny versus God's will, for instance) accepted by Pastor Park in the course of his search for the truth ends up reaffirming his (Christian) faith in God, instead of subverting it. The memorable and surprisingly somber final scene of the film has him uttering a heartfelt entreaty to God, asking the latter to save us mortals from our own hubris and blind will to power.

Fascinating theological-religious questions raised by the present film aside, director Jang expertly wrangles horror set pieces, although the droll humor is a bit subdued this time around, and at two hours and two minutes, the motion picture is somewhat, though not fatally, overlong. The cast is dependably good: Lee Jae-in proves her gumption in a tricky dual role (although perhaps not quite as endearing as The Priests' Park So-dam), and Yu Ji-tae (Oldboy, The Swindlers) is excellently cast as an enigmatic custodian of the Deer Hill properties, charismatic and creepy in equal measure. DP Kim Tae-soo (Collective Invention, Microhabitat), Lighting Director Jeon Young-seok, Production Designer Seo Sung-kyung all do credible jobs, believably assembling together such realistic yet fantastic settings as the Deer Hill prayer rooms with striking murals of wrathful Deva Kings.

Svaha is perhaps a tad more difficult to approach than The Priests, especially for Euro-American viewers unfamiliar with its (non-Zen) Buddhist mythology, and some may also feel that the film throws in one too many surprise revelations and expository dialogues to tie up all the loose ends in the latter half (which it does satisfactorily, no mean feat in my opinion). Nonetheless, it ultimately shapes up to be an extravagantly entertaining red-meat horror flick that refuses to condescend to its genre thrills, and to treat them as baits for allegorical ruminations about the dark side of human existence, as some "artistic" horror films are wont to do. Jang Jae-hyun scores a solid hit again, and I for one would be looking forward to his next project, all but certain to be another intriguing, sui generis genre opus. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

The Sewol Ferry sinking on April 16, 2014 stands as the biggest collective trauma leveled on South Korean society in the past decade. Of the 304 people killed in the accident, 250 were students and teachers from Danwon High School in Ansan City, who were traveling on a school trip. Not only did the tragedy devastate a community (and the rest of the nation, who watched helplessly on TV as the ship went down in real time), it produced a flood of unanswered questions: Why did the ship sink? Why wasn't a fast and effective rescue operation carried out? Why did the government try to cover up key details about the accident? What should be done to ensure that such an incident will never happen again?

In the years since, quite a few films and documentaries have been made to grapple with these and other lingering questions. The politics surrounding the incident have grown only more bitter and divided with time. Now, exactly five years after the sinking, the film Birthday has emerged with a very focused objective. Avoiding overt references to politics or to the cause of the sinking, Birthday simply aims to give voice to the grief of the bereaved families.

In the years since, quite a few films and documentaries have been made to grapple with these and other lingering questions. The politics surrounding the incident have grown only more bitter and divided with time. Now, exactly five years after the sinking, the film Birthday has emerged with a very focused objective. Avoiding overt references to politics or to the cause of the sinking, Birthday simply aims to give voice to the grief of the bereaved families.

The plot centers around Jung-il (Sul Kyung-gu), the father of one of the victims, who returns to Korea after years spent running a factory in Vietnam. His return causes a bit of a stir. He needs to be introduced to his young daughter Ye-sul, who doesn't recognize him. It also soon becomes clear that his wife Soon-nam (Jeon Do-yeon) does not want anything to do with him. One only needs to look at Jung-il's face to understand that he is suffering, and haunted by the death of his son. But the process of reconnecting with his family is complicated, and takes time.

Soon-nam, meanwhile, is only barely hanging on. Her son's room remains exactly as it was when he left to go on that school trip. In her community, she sometimes runs into other parents or classmates of the children who died, but for the most part, she tries to avoid them. At this point, a member of a volunteer group arrives and makes a suggestion. Her son's birthday is approaching, and the volunteer offers to organize an event in his memory. It will be a birthday celebration, of a kind, where people who knew him gather to share their stories.

The Korean film industry is known for turning out a lot of tear-jerkers, but that term feels wrong as a description of this film. Debut director Lee Jong-un, who worked on the production team of Secret Sunshine and Poetry by Lee Chang-dong (who serves as a producer on this film), takes a nuanced approach to extremely emotional material. The hugely accomplished leads Sul Kyung-gu and Jeon Do-yeon take care not to exaggerate or embellish the parents' grief. But it's because of this measured approach that the film becomes so devastatingly sad by the end. Watching it is an intense, exhaustive and cathartic experience. Stories abound of strangers bonding in movie theaters over shared packs of Kleenex.

It may be that some viewers, particularly outside of Korea, feel alienated by the raw, communal expressions of grief in the film's final half hour, which depicts the birthday event of the film's title. But they do seem true to life. Director Lee based the script on her own observations while volunteering with bereaved families in the aftermath of the tragedy. In the coming years she became close to many of the families, and also attended events such as the one depicted in Birthday. Such gatherings, it seems, have been effective in helping families cope with their grief, and perhaps this film might serve a similar role, too. (Darcy Paquet)

So-hee (Jung Eun-ji of the k-pop girl group A-pink) is a sullen-looking member of a college extracurricular club called "0.0MHz," allegedly referring to the moment when the human brain-wave signals zero activity and thus could invite the supernatural presence to declare itself. Led by the suave Han-seok (Shin Ju-hwan, Hit-and-Run Squad), the gang, consisting of the irritable and sleazy Tae-soo (Jung Won-chang, The Battleship Island), the foxy Yoon-jeong (Choi Yoon-young, Horror Stories) and the rookie Sang-yeop (Lee Sung-yul of the k-pop boy group Infinite), decides to investigate an isolated haunted house in which a young woman had hanged herself (and already caused the death of a shaman in the prologue), clearly not taking its notoriety too seriously. So-hee reluctantly joins them, hiding from them her maternally-inherited ability to actually see the spirits of the dead. Sure enough, the vengeful ghost of the suicide victim appears for real and takes possession of Yoon-jeong, forcing So-hee to revisit her dormant skills as a medium-exorcist in order to save the lives of her college friends.

Yet another thriller based on a webtoon series, a popular debut comic by Jangjak, whose Gwishin (Ghost) is a rare item, a straightforward horror story set during the colonial period (hopefully a cinematic adaptation is in the works?), 0.0MHz quickly does away with the gimmick of using medical technology to spot the moment of supernatural advent, and focuses on the confrontation between So-hee and the ghost, who eventually manifests herself as a decapitated head using her locks like tentacles to grab hold of her victims and infiltrate their brains. Adapted for screen and directed by Yoo Seon-dong (Death Bell 2: Bloody Camp, The Quiz King, although he seems to be doing better these days as a mystery writer. His novel The Purloined Book won accolades and was adapted into a play and, yup, a webtoon), the film covers familiar territories for a mid-range budget summer horror. It evokes both classics of the genre such as Evil Dead as well as a few well-known tropes of J-horror such as Ito Junji's Tomie series and Sono Sion's Exte: Hair Extensions (2007), generating an almost comfortable sense of déjà vu.

Yet another thriller based on a webtoon series, a popular debut comic by Jangjak, whose Gwishin (Ghost) is a rare item, a straightforward horror story set during the colonial period (hopefully a cinematic adaptation is in the works?), 0.0MHz quickly does away with the gimmick of using medical technology to spot the moment of supernatural advent, and focuses on the confrontation between So-hee and the ghost, who eventually manifests herself as a decapitated head using her locks like tentacles to grab hold of her victims and infiltrate their brains. Adapted for screen and directed by Yoo Seon-dong (Death Bell 2: Bloody Camp, The Quiz King, although he seems to be doing better these days as a mystery writer. His novel The Purloined Book won accolades and was adapted into a play and, yup, a webtoon), the film covers familiar territories for a mid-range budget summer horror. It evokes both classics of the genre such as Evil Dead as well as a few well-known tropes of J-horror such as Ito Junji's Tomie series and Sono Sion's Exte: Hair Extensions (2007), generating an almost comfortable sense of déjà vu.

The production design team headed by Lee Si-hoon has done a fine job of creating an atmospherically decrepit country house, while the SFX staff including Lee Sang-min (Jeil M.S.), MOMOTO and Robofix Digital, along with the special makeup effects crew headlined by Lee Joo-hwan (FXLab), provide adequate, if not exceptional, visuals, perhaps reined in by the limited budget. To be a bit hair-splitting (pun unintended), the coarse, wiry texture of the ghost's tresses is rendered very nicely, while its actual visage looks disappointingly goofy. To be fair, the source webtoon itself, like many of its kind, relies on good characterization and complex narrative rather than innovative imagery, so the filmmakers could not exactly rely on it for rendering the ghost convincingly cinematic. I would also like to give high points to composer Kim Woo-geun (House of the Disappeared), whose pulsating score makes knowing references to a few genre staples, such as Michael Oldfield's tubular bells for The Exorcist. The young cast proves game to the demands of a horror thriller, Shin, Jung and Choi doing thespian heavy-lifting while Sung-yul appears appropriately shy and cute. I feel that So-hee's morose characterization is a mismatch to Jung's natural charms, but she proves a trouper nonetheless, and has a good chemistry going with the fellow k-pop idol Sung-yul.

0.0MHz did receive some positive reviews but overall box office performance was lukewarm at best, collecting approximately 137 thousand tickets in its two months of theatrical runs. It is in the end a rather conventional horror film, not advancing the Korean horror much beyond the template established in early '00s. For what is its worth, I found the film's twist ending moderately interesting, in the sense that it seems to betray its premise and question the efficacy of shamanistic rituals at the center of the film. In other words, the movie appears to acknowledge in an underhanded way that the (anti-misogynistic) rage of a contemporary Korean (female) ghost is way too powerful (too real?) to be contained or exorcised by the shamans who berate and scold the dead spirits as if they are drill sergeants bullying rookie recruits, as the cultural convention dictates. Perhaps the Korean exorcists should have attempted to sympathetically listen to the ghost and even help the latter go after those who had driven her to death? That might have struck the female viewers as at least refreshing, and could not have hurt its box-office fortunes either. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

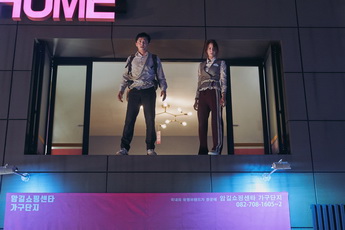

Yong-nam (musical star Jo Jeong-seok, The Face Reader) is considered an embarrassment by his three elder sisters and even his grade-school nephew, partly due to his inability to find gainful employment. Put to a series of menial jobs for a family party celebrating his mother's (veteran Go Doo-shim) seventieth birthday at a schlocky local banquet hall, he is reunited with the object of his college-day infatuation, Eui-joo (Im Yoon-ah, better known as Yoona of the world-famous K-pop group Girl's Generation), presently Vice-Chief of the banquet hall service team. It turns out that despite their awkward memories of misfired romance, they still retain a love for mountain climbing to which they had seriously committed as college athletes. Meanwhile, a man wearing a gas mask (Park Chae-ik, The Exclusive: Beat the Devil's Tattoo) drives a tanker into a nearby chemical corporation and unleashes clouds of poison gas. The lethal mist begins to spread all over the city, gradually filling up the streets, killing pedestrians and gawkers alike and slowly ascending toward the upper levels of taller buildings. Yong-nam and Eui-joo manage to herd the former's family members and other survivors to temporary safety inside the banquet hall building, but time is running out: they must reach the building's rooftop before the government can enact a rescue.

Exit, an RnK co-production (Director Ryoo Seung-wan and his wife Kang Hye-jung's company) written and directed by Lee Sang-geun, a former assistant director to Ryoo, is a surprisingly adroit crowd-pleaser expertly cooking up a contemporary Korean variant of a '70s-style Hollywood disaster film utilizing familiar, even stale, ingredients. Laced with coarse but efficient humor, Exit is tightly constructed as a thrilling obstacle course, with little melodramatic dilly-dallying and, most refreshingly, minus the eruption of self-righteous political anger that mar similar-themed blockbusters such as The Terror Live or Tunnel. Even though the 1995-Tokyo-sarin-gas-attack-like chemical terror that plunges the local Korean city into a living nightmare is not exactly rendered entirely believable (and the gas's ultimate "self-cleaning" just a bit irresponsible plot-wise), it is never used by the filmmakers to vent frustrations against the government or news media. If anything, they openly advocate common-sense preparedness and rational thinking, such as reading manuals when dealing with the equipment to be used in the times of extreme emergency. Imagine that, a disaster movie in which the hero actually saves lives by consulting a manual!

Exit, an RnK co-production (Director Ryoo Seung-wan and his wife Kang Hye-jung's company) written and directed by Lee Sang-geun, a former assistant director to Ryoo, is a surprisingly adroit crowd-pleaser expertly cooking up a contemporary Korean variant of a '70s-style Hollywood disaster film utilizing familiar, even stale, ingredients. Laced with coarse but efficient humor, Exit is tightly constructed as a thrilling obstacle course, with little melodramatic dilly-dallying and, most refreshingly, minus the eruption of self-righteous political anger that mar similar-themed blockbusters such as The Terror Live or Tunnel. Even though the 1995-Tokyo-sarin-gas-attack-like chemical terror that plunges the local Korean city into a living nightmare is not exactly rendered entirely believable (and the gas's ultimate "self-cleaning" just a bit irresponsible plot-wise), it is never used by the filmmakers to vent frustrations against the government or news media. If anything, they openly advocate common-sense preparedness and rational thinking, such as reading manuals when dealing with the equipment to be used in the times of extreme emergency. Imagine that, a disaster movie in which the hero actually saves lives by consulting a manual!

One of the film's highlights involves Yong-nam's crazy stunt of bare-handedly scaling the walls of the banquet hall to reach the rooftop, a sequence that makes exceedingly clever use out of the super-kitschy décor of the building to generate sweat-in-the-palm suspense and unexpected humor in the equal measure. DP Kim Il-yon (The Silenced), lighting supervisor Kim Min-jae (The Front Line), editor Lee Gang-hee (Steel Rain) and production designer Chae Kyung-seon (The Fortress) all help out in keeping the action slick and motivated, the gaseous threat suitably menacing and the obstacles faced by the hapless protagonists both ludicrous in scale and gorgeous in its night-sky resplendence. Exit in fact presents an interesting showcase in its incorporation of drone videography into its visual storytelling, as Yong-nam and Eui-joo end up being aided by YouTuber gadflies sending off their camera-eyed drones to capture the "money shots." As for characterizations, I wish both Yong-nam and Eui-joo were conceived as a bit "cooler:" their boisterous and face-crunching responses to every situation that go south are admittedly funny, but become rather tiresome by the two-thirds point. The young actors nonetheless acquit themselves without a problem: Yoona is certainly very attractive as a lanky beauty whose jaw-dropping physical exertions throughout the movie come off as realistic and in character (all that K-pop dance training apparently did not go anywhere else, after all).

Exit, opening July 31 against the highly anticipated Song Kang-ho star vehicle The King's Letters and an industry-predicted heavy hitter for the summer horror market The Divine Fury, trounced both and raked in 9.4 million tickets, just short of the coveted 10 million mark, yet still ahead of Spider-Man: Far From Home and The Lion King in terms of domestic box office performance. It is pretty obvious that good word of mouth significantly contributed to its success, at least as much as CJ's strong PR push. You could attempt to decipher the younger generation's frustration from the movie, but its very commercial success suggests that domestic viewers favored it precisely because it was a committed escapist piece. Personally, I wish its rather belabored comedic depiction of the family relations had been toned down (Bong Joon Ho's The Host or Parasite might have served as a good model), but this minor gripe does not take much away from the fact that Exit is a superbly entertaining concoction, clever and nimble, as well as a promising debut for the writer-director Lee Sang-geun. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Yong-hoo, a young mixed martial artist (Park Seo-joon, who plays the protagonist Ki-woo's rich high school buddy in Parasite) is subject to incomprehensible nightmares and also showing symptoms of stigmata, even though he disavows any faith in God or anything else. Meanwhile, Father An (the super-veteran Ahn Sung-ki) is busy exorcising a group of demons trying to possess Seoulites. He deduces that a young nightclub owner and businessman Ji-sin (Woo Do-hwan, Master) might be the head of a devil-worshipping cult seeking to unleash the Satanic pandemonium in the Gangnam district, and presumably in the rest of Seoul (Wait, hasn't he done that already in 2016? Um¡¦ my apologies, that was pretty lame). And wouldn't you know it, Yong-hoo has been designated by the higher forces to serve as a Divine Warrior in Father An's battle against Ji-sin and his minions. It is up to Father An to convince the scowling young punk to save the souls of millions of Seoulites against the machinations of the serpentine Ji-sin.

This latest feature from Kim Joo-hwan, a former Showbox PR-expert-turned-screenwriter-and-director, who scored a hit with Midnight Runners in 2017, is yet another vaguely Catholic, exorcism-themed supernatural thriller, following in the trail cropped by Jang Jae-hyun's The Priests (2015) and closely followed in release schedule by Metamorphosis, also featuring an exorcist-priest. In terms of box office performance, The Divine Fury did not do too badly for a summer horror film (with approximately 1.29 million tickets sold), but was trounced by its direct box office competition Exit, and eventually outperformed by not only Jang Jae-hyun's new film Svaha: The Sixth Finger but also Metamorphosis. Apparently, the movie is based on Kim's original screenplay, but the movie reeks of the kind of hypermasculine, Marvel Comics-blockbuster-wannabe sensibility plus an obsession with the jerry-rigged construction of an elaborate fictional universe, a hallmark of South Korean webtoon adaptations of recent years.

This latest feature from Kim Joo-hwan, a former Showbox PR-expert-turned-screenwriter-and-director, who scored a hit with Midnight Runners in 2017, is yet another vaguely Catholic, exorcism-themed supernatural thriller, following in the trail cropped by Jang Jae-hyun's The Priests (2015) and closely followed in release schedule by Metamorphosis, also featuring an exorcist-priest. In terms of box office performance, The Divine Fury did not do too badly for a summer horror film (with approximately 1.29 million tickets sold), but was trounced by its direct box office competition Exit, and eventually outperformed by not only Jang Jae-hyun's new film Svaha: The Sixth Finger but also Metamorphosis. Apparently, the movie is based on Kim's original screenplay, but the movie reeks of the kind of hypermasculine, Marvel Comics-blockbuster-wannabe sensibility plus an obsession with the jerry-rigged construction of an elaborate fictional universe, a hallmark of South Korean webtoon adaptations of recent years.

The characterizations are relentlessly shallow. Yong-hoo is utterly lacking in charm or intelligence, and as conceived and directed by Kim, not believable at all as a tragic hero struggling with his own failing faith in the greater meanings of life. At least we are spared of the kinds of brain-melting one-liners that untalented American screenwriters would have poured over a character like this. Mr. Ahn, now in late 60s, has been rendering support for indie and arthouse projects in recent years (such as Zhang Lu's Love and¡¦ [2015]). I cannot help but wonder what made him choose this project over other potential choices available to him, especially since this role is uncomfortably similar to the demon-fighting Catholic priest he had played more than twenty years ago in The Soul Guardians (1998). In any case, he projects an appropriate level of authority and sincerity, even while delivering the irredeemably hackneyed "We must fight the evil nonetheless" platitudes. Woo Do-hwan as the vaguely hermaphroditic bad guy Ji-sin comes off as more interesting, even though ultimately hampered by the layers of reptilian latex makeup he has to wear for the climax. Frankly the whole project would have been serviced better, if its weight had shifted toward Ji-sin as an aggressively allegorical anti-hero, a personification of all that is superficially decadent, pettily hypocritical and power-worshipping in a sub-Nietschean way about Seoul's Gangnam district: say, something in the line of the TV series Lucifer, but less comedic and self-referential.

In fairness, The Divine Fury does not do too badly in the technical departments. Production designs and art direction by Lee Bong-hwan (Confession) with contributions by Park Jun-yong and Kim Hak-hyeon are pretty impressive, especially the organically creepy sets and slimy props constructed for Ji-sin's black magic rituals. The film's numerous action and special effects sequences are not conceptually special but are serviceable, supported by good works from the SFX make-up specialist Pi Dae-sung (Veteran, New World) and the VFX maven Dexter Studio (Along with the Gods).

Given the Key East-Lotte Entertainment's aggressive PR push for the project and considering its not-too-bad box office figures, it is possible that a sequel may be in the works, but my heart is not exactly beating faster in anticipation of one. The Divine Fury is, given the considerable talents involved, way too formulaic and quotidian. Overall, it is geared more toward those who want their Hollywoodized supernatural action-thriller sizzling on the outside but not too meaty inside, neither genuinely perverse nor disturbing, than toward the committed fans of horror genre. As it stands, it's loud and fast-moving, full of muscular fistfights and light shows seasoned with the PG-13 level icky gore, but empty: many of you will forget about it an hour after you had watched it. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Mi-jeong (Seo Ye-ji, The Throne), a nerdy film school graduate, is preparing to complete a horror film screenplay that will launch her directorial career. Unfortunately, she is stuck with a writer's block. When her assistant Joon-seo (Ji Yoon-ho, In Between Seasons) brings up an urban myth about a debut horror film that was supposedly so scary that it ignited a pandemonium at its first unveiling, even bringing a massive coronary attack on one luckless viewer, she is intrigued despite herself. Mi-jeong does some digging, and to her surprise, discovers that the film was not a myth (it was even screened at Bucheon Fantastic Film Festival!) and its director Jae-hyun (Jin Seon-gyu, Extreme Job), who had claimed that "a ghost directed that movie!" to the derision and confusion of those around him, is still very much alive, albeit hiding from the public. Not surprisingly, an interview with the latter ends in a disaster, yet she manages to download a surviving video file of the so-called cursed film. What she sees is the crude footage of Jae-hyun's rookie film crew being killed off by an unseen assailant in a creepy, decrepit old movie theater. Then, Mi-jeong locates that very movie theater in which the now-deceased crew was trying to film the seemingly insane director's screenplay¡¦

Warning: Do Not Play marks a return by director Kim Jin-won, whose debut feature The Butcher (2007) is definitely one of the goriest and most extreme horror films ever made in South Korea. It was banned from domestic theaters after playing to an enthusiastic audience at the 11th Bucheon Film Festival in the Forbidden Zone section, but eventually managed to attain a minor cult status among gorehounds and horror fans, not surprisingly receiving a stateside DVD release from then-notorious Palisade Tartan's "Extreme Asia" label (with really terrible English subtitles, I must add). I remember finding The Butcher, having initially approached it with the lowest level of expectations, surprisingly intelligent, something of a very sick joke on the pain, nay, torment of filmmaking process rather than a mindless gorefest that it was purported to be.

Warning: Do Not Play marks a return by director Kim Jin-won, whose debut feature The Butcher (2007) is definitely one of the goriest and most extreme horror films ever made in South Korea. It was banned from domestic theaters after playing to an enthusiastic audience at the 11th Bucheon Film Festival in the Forbidden Zone section, but eventually managed to attain a minor cult status among gorehounds and horror fans, not surprisingly receiving a stateside DVD release from then-notorious Palisade Tartan's "Extreme Asia" label (with really terrible English subtitles, I must add). I remember finding The Butcher, having initially approached it with the lowest level of expectations, surprisingly intelligent, something of a very sick joke on the pain, nay, torment of filmmaking process rather than a mindless gorefest that it was purported to be.

Even though some clips from The Butcher are shown in the opening section, I was not aware that Warning: Do Not Play was a sophomore feature from the same director, until I had finished the film. On surface, there is little resemblance between the two works. Kim steers clear of the uncomfortably mock-snuff, torture porn ambience of his debut feature and instead unspools his narrative in a fairly straightforward manner, closely following Mi-jeong's journey into the abyssal depths of both supernatural terror and her own obsession to create a truly frightening motion picture. Indeed, Warning shares Kim's self-reflexive stance with the earlier work, in the sense that he appears to be exploring the deeply paradoxical allure of the horror cinema here as well.

At one point, Mi-jeong watches an EPK video of Jae-hyun being inquired about his motivation for becoming a filmmaker. The latter delivers a passionate confessional about how he once watched The Exorcist (1973) as a teen and found it mind-shatteringly frightening, and then transcendentally cathartic: Mi-jeong, while listening to Jae-hyun, recalls (or, more likely, fabricates in her memory) an identical experience, of watching The Exorcist in a hospital ward after attempting to kill herself (there are intimations of the episodes of sexual abuse by a family member), and being endowed with the renewed purpose of life. (One of this film's semi-autobiographical detail, although, according to a Cine 21 interview, it was apparently Sam Raimi's The Evil Dead [1981] that "saved" Kim's life from drowning in meaninglessness, rather than the William Friedkin film)

For my part, I found this sequence strangely poignant, a genuinely earnest probing of the kind of question that might haunt a committed fan of horror in his or her unguarded moments: if all those cinematic gore and terror are not merely consumed for my sadistic pleasure, then what purpose do they actually serve? One could interpret Warning as an allegory for the real-life exploitation and harm that could result from an unbridled obsession over creating art, or at least over generating real affective response from the others: Mi-jeong, no matter how frightened or endangered she is, pointedly never forgets to take a snapshot- of a bloody, dying man, of a dreadful apparition in conflagration, of any cinematic object- with her trusted smartphone camera.

I concede that some viewers might be irritated or nonplussed by all these meta-diegetic reflections on the part of director Kim. Thankfully, Warning works quite well as a "regular" horror film, especially when the protagonist has to contend with the supernatural in the impressively squalid movie theater setting (apparently this was a real old Gunsan city theater fallen into disuse, not a freshly constructed movie set). I should add, too, that, although the film is clearly low budget, the technical level is pretty high. Cinematographer Yoon Young-soo (Steel Rain) and Lighting Director Ryoo Si-moon (The Spy Gone North) anchor the widescreen vistas in hues of inky black and coruscated red, maintaining a steady tone of crisp dread throughout the film. Production design supervised by Kim Hyo-shin (Good Morning Mr. President, The Quiz Show Scandal) is likewise unobtrusively effective, emphasizing the angular and cold features of Mi-jeong's apartment and other "normal" spaces, in contrast to the more organically putrid texture of the old movie theater.

I concede that some viewers might be irritated or nonplussed by all these meta-diegetic reflections on the part of director Kim. Thankfully, Warning works quite well as a "regular" horror film, especially when the protagonist has to contend with the supernatural in the impressively squalid movie theater setting (apparently this was a real old Gunsan city theater fallen into disuse, not a freshly constructed movie set). I should add, too, that, although the film is clearly low budget, the technical level is pretty high. Cinematographer Yoon Young-soo (Steel Rain) and Lighting Director Ryoo Si-moon (The Spy Gone North) anchor the widescreen vistas in hues of inky black and coruscated red, maintaining a steady tone of crisp dread throughout the film. Production design supervised by Kim Hyo-shin (Good Morning Mr. President, The Quiz Show Scandal) is likewise unobtrusively effective, emphasizing the angular and cold features of Mi-jeong's apartment and other "normal" spaces, in contrast to the more organically putrid texture of the old movie theater.

Warning is lean at one hour and 26 minutes, but make no mistake, it is a bona fide red meat horror film, with the nods to the Expressionist manipulation of time and space to disorient, but not confuse, the viewers. Kim deserves high marks for his skills in wrangling the expected horror effects, but the film, for me at least, would not have worked, had it been cast with a conventional male actor in the part of Mi-jeong. Seo Ye-ji, best known for essaying a victimized teen beauty in the TV drama Save Me, does an excellent job with what amounts to be a rather restrained role that eschews obvious histrionics. As a chance to showcase her acting range, Mi-jeong is not a bad choice at all for Seo, and she ultimately manages to capture the sincerity that underlies the former character's dangerous obsession.

When Joon-seo professes his admiration for her ambition and readiness to face adversity, Mi-jeong softly dismisses the praise, saying, "I am not good, I am just crazy." Well, whatever it takes to make a good, scary yet thoughtful horror film. Count me as one more horror film fan now signed up for Kim Jin-won's next project. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

It's perhaps a natural human instinct to try to shield children from knowledge of life's cruelties and injustices. Parents may try to filter the information that reaches children's ears, or even lie to them to avoid delivering painful truths. But it's also true that children usually figure out the reality of a situation pretty quickly on their own. If parents are reluctant to discuss things out loud, that may just mean that the kids are on their own when it comes to processing and dealing with the issue.

Films about children often follow a similar pattern. It's rare to find a movie that acknowledges that even so-called normal childhoods are often punctuated with moments of deep anxiety or uncertainty. In this sense, the works of director Yoon Ga-eun are a welcome departure. The House of Us is a film about three girls. Hana, 12 years old, watches her parents' constant fighting and senses that their marriage might not last much longer. Desperate to avoid a separation, she hits upon an idea of a family trip with the hope that it might bring all of them closer together. But her older brother scoffs at the idea, and given everyone's busy schedule, her plan won't be easy to carry off.

Films about children often follow a similar pattern. It's rare to find a movie that acknowledges that even so-called normal childhoods are often punctuated with moments of deep anxiety or uncertainty. In this sense, the works of director Yoon Ga-eun are a welcome departure. The House of Us is a film about three girls. Hana, 12 years old, watches her parents' constant fighting and senses that their marriage might not last much longer. Desperate to avoid a separation, she hits upon an idea of a family trip with the hope that it might bring all of them closer together. But her older brother scoffs at the idea, and given everyone's busy schedule, her plan won't be easy to carry off.

One day by chance she gets to know two younger girls, Yoo-mi and Yoo-jin, who live in the same neighborhood. Clearly from a lower economic class, the two girls are alone on most days, with their parents working in another city. Having relocated so often that no place they've lived in ever really feels like home, they find out from their landlord that this time too, another move is imminent. Seeing how upset the girls are, Hana convinces them to try out a plan that will let them stay in their current home.

The title of the film (in Korean, it is simply "Our House") reflects how both stories are about children trying to keep their homes together. At the same time, it's about the newly formed relationship between the three girls, and how Hana comes to play the role of an older sister to them. The House of Us is not all gloom and hardship -- a big part of it is about kids having fun together -- but at the same time, director Yoon Ga-eun never romanticizes the girls' situation or offers false solutions.

Director Yoon's debut feature The World of Us was also told from the perspective of child protagonists, and it received widespread praise for its subtle performances and honest portrayal of what growing up is like. Fans of that work will enjoy spotting parallels in this film, including the way it opens and closes with long closeups on the face of the protagonist listening to those around her. Each of the main characters in The World of Us also appear briefly in the new film in cameo roles.

Actress Kim Na-yeon appears in her first major film role as Hana, whereas Kim Si-ah who portrays Yoo-mi has appeared in numerous films including Miss Baek (2018), Ashfall (2019) and The Closet (2020). It's a bit ironic that Kim Si-ah's performance gives the impression of being less "polished" than her co-star's, but it is also tremendously effective, suggesting a strong natural talent that should make her worth watching in the years to come.

The natural question to ask after watching this film is whether Yoon Ga-eun will direct a third feature in order to complete a trilogy. One certainly hopes so -- in these two films she has refined a style and approach all her own, and there's no question she brings something new and distinctive to contemporary Korean cinema. (Darcy Paquet)

Tracing the story of Eun-hee, a 14-year-old girl and the youngest daughter in a family of five, House of Hummingbird, Kim Bora's full-length directorial debut, is extraordinary for the way it traverses both violence and beauty—the invisible scars that form behind closed doors, but also the small sustaining graces that can be found in the most unexpected places. Indeed, the soul of the film is exquisitely captured by one of the film's final lines, a voice-over by Young-ji, Eun-hee's (Park Ji-hoo) beloved classical Chinese teacher (played by Kim Sae-byeok, A Resistance): "Even as there are ugly moments, they come together with beautiful ones... Life is so wondrous and beautiful." The film takes place in Seoul, 1994, a setting that that adds a deeper layer of meaning to the film's diegetic plot. Throughout the film, Kim Bora continues to masterfully weave in the historical context of 1994 Korea with Eun-hee's personal life, primarily through shots of television news programs that announce momentous events such as the abrupt death of Kim Il-sung and the shocking collapse of the Seongsu Bridge that killed thirty-two people. Though these pivotal historical events undoubtedly serve as a reminder of how turbulent and precarious South Korea in the 1990s was, they are never relegated to the abstract realm of History and politics. And even as the government changed to a more democratic one, with the election in 1992 of Kim Young-sam, the first civilian President after thirty years of military dictatorship, the ethos of developmentalism, modernization, and capitalism remained constant, spurring numerous building projects (such as the plethora of monotonous apartment complexes like the one Eun-hee lives in, and the Seongsu Bridge) that were shoddily and quickly made for the sake of profit. What Kim Bora does exceptionally well is emphasize how these larger historical events inevitably bleed into the lives of ordinary citizens, and it is precisely these everyday people that suffer under the larger abstractions of history. In other words, that interpersonal and systemic cruelties are not mutually exclusive, but inextricably intertwined.

Eun-hee and her family are a part of this broad swathe of society broken by the burdens of rapid development and capitalism. Barely eking out a living by running a rice cake shop, the entire family, including all three children, are forced to participate in this backbreaking and thankless work. The film depicts all three children at the shop, slicing, stirring, packing and at the end of the day, sitting in the living room of their tiny apartment and counting out the money they made—money that never seems to be quite enough. The stark contrast between the sheer amount of labor required to survive and the toll it takes on their physical bodies only serves to underscore the cruelty of what a working-class family's life would have been like then (and of course, continues to be like today). It is a life that slowly robs children of an innocent childhood, that renders their home into an empty place of exhaustion and deadened silence. In a reversal of roles, we see moments where Eun-hee takes care of her mother—shots from Eun-hee's perspective of her mother's callused and worn-out feet from standing all day, her exhausted form as she lays napping on the couch, asking Eun-hee to apply pain relief medicine on her shoulder.

Eun-hee and her family are a part of this broad swathe of society broken by the burdens of rapid development and capitalism. Barely eking out a living by running a rice cake shop, the entire family, including all three children, are forced to participate in this backbreaking and thankless work. The film depicts all three children at the shop, slicing, stirring, packing and at the end of the day, sitting in the living room of their tiny apartment and counting out the money they made—money that never seems to be quite enough. The stark contrast between the sheer amount of labor required to survive and the toll it takes on their physical bodies only serves to underscore the cruelty of what a working-class family's life would have been like then (and of course, continues to be like today). It is a life that slowly robs children of an innocent childhood, that renders their home into an empty place of exhaustion and deadened silence. In a reversal of roles, we see moments where Eun-hee takes care of her mother—shots from Eun-hee's perspective of her mother's callused and worn-out feet from standing all day, her exhausted form as she lays napping on the couch, asking Eun-hee to apply pain relief medicine on her shoulder.

Indeed, some of the most memorable moments in the film are its scenes of domesticity—or more precisely, of broken domesticity. The home is not a site of warmth and love, but a place of violence and silence, often shot in muted and darker tones in comparison to the lush light and greenery that mark the majority of the outdoor shots. And this violence is unquestionably gendered—Eun-hee's father (Jung In-ki, Unstoppable) hits Eon-hee's older sister, Soo-hee (Park Su-yeon, Second Life) and her mother (Lee Seung-yeon, The Running Actress), while their brother Dae-hoon (Son Sang-yeon) is for the most part doted upon and praised. In one scene, after Eon-hee is brutally beaten by her brother for talking back, the family is seated around a small dinner table, cramped close together, but for all their physical proximity, they are worlds apart. While the rest of the family is submerged in silence, the father goes on a monologue complaining about their rice cake business and how hard he works while the children are lazy and ungrateful. Eun-hee then abruptly speaks up, announcing that Dae-hoon hit her earlier that day, but her words are quickly passed over. It is these tense scenes at the dinner table in which everything feels like it will explode in an instant that best exemplify the way the exhaustion of working-class life ignites a boiling rage that lies underneath a seeming placid surface.

But instead of falling into the easy trap of unilaterally blaming all men for this violence or essentializing gender, Director Kim Bora takes special care to show how, under these enforced systems of patriarchy and capitalism, men suffer as well—that no one can escape without their own scars. Like many families, Eun-hee's parents fervently believe that education will be their children's (and by extension, their own) escape from the pains of working class life and poverty. Eun-hee's mother muses on about her dreams of seeing Eun-hee as a college student, vicariously imagining the latter carrying her books across the college campus. Her father constantly drills into them the need to study and work hard, though he of course pays special attention to "the male heir" Dae-hoon, constantly pushing him to get into Seoul National University, the emblem of ultimate success. Without excusing the violence these men inflict, House of Hummingbird also shows the deep pain that men feel under the pressures of conforming to certain types of masculinity, of being a stoic provider for the entire family.

Her parents too busy at work, Eun-hee is forced, like many children of working-class families, to grow up far too quickly. She takes herself to the hospital to get her ear examined, makes herself meals, spends time primarily alone at home. In other words, she seems capable and independent because she is forced, by circumstance, to become so even as she yearns (quite naturally) for affection and care—which she receives from her classical Chinese hagwon teacher, Youngji. And it is with Youngji that Eun-hee finds the love she so longs for, the encouragement to chase her dreams, and the permission to gently unfold and fully inhabit the world. There is something so right about how Kim Bora captures the pain and intensity of emotions during adolescence—the sadness but also exuberance of feeling everything anew. Though the dissonant juxtaposition of silence and angry screams comprises the soundscape of home, the outside world is threaded with the sounds of nature—the perpetual thrum of the wind blowing through the trees and the summer cicadas, bathed in the warm and luminous sunlight. In this sense, House of Hummingbird is not only about pain, but the mysterious beauty in our lives.

Her parents too busy at work, Eun-hee is forced, like many children of working-class families, to grow up far too quickly. She takes herself to the hospital to get her ear examined, makes herself meals, spends time primarily alone at home. In other words, she seems capable and independent because she is forced, by circumstance, to become so even as she yearns (quite naturally) for affection and care—which she receives from her classical Chinese hagwon teacher, Youngji. And it is with Youngji that Eun-hee finds the love she so longs for, the encouragement to chase her dreams, and the permission to gently unfold and fully inhabit the world. There is something so right about how Kim Bora captures the pain and intensity of emotions during adolescence—the sadness but also exuberance of feeling everything anew. Though the dissonant juxtaposition of silence and angry screams comprises the soundscape of home, the outside world is threaded with the sounds of nature—the perpetual thrum of the wind blowing through the trees and the summer cicadas, bathed in the warm and luminous sunlight. In this sense, House of Hummingbird is not only about pain, but the mysterious beauty in our lives.

Upon my third viewing of the film, a passage from Vietnamese poet Nhã Thuyên's Moon Fevers (trans. by Kaitlin Rees) flashed in my mind:

to [me],

you grow up wanting to be identity-less neither woman or man, you still are a species of soft body-fate wishing to warm up. you have labored so much. you have multiplied to become EVERYTHING in ONE, though you do not need to be so, to you, keep being a child, you play and play and deserve peaceful love. please let the innocent ignorance stay in the heart, and let the ugly ignorance stay with those narrow ones who do not erase their narrowness.

There is an aching loneliness that I immediately recognized. Watching House of Hummingbird compelled me to remember my own childhood, the violence we tried to hide, the façade we put up, the hidden bruises and sleepless nights from listening to my parents scream. I think of all the girls in the world that were forced to grow up too quickly, who learned how to hide their scars and project an image of self-sufficiency and capability to hide the immense yearning for tenderness and care that rested somewhere inside, lodged deep inside like a stone. And though I am not religious, I think of them and I send a prayer out into the world — that you, too, may someday fly away, into the arms of the tenderness you so deserve. (Rachel Min Park)

There's no question that there is a generational element to romance and dating, particularly in a fast-evolving society like South Korea. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, romantic comedies like Art Museum by the Zoo and My Sassy Girl captured young people's hopes of finding love in the midst of a chaotic and confusing world. But two decades later, romance and relationships are being described in starker terms. The younger generation doesn't have the time or money to engage in dating, we are often told. People claim this has resulted in a more transactional, transient nature to relationships in the current era. There is also a striking gender split among twentysomethings when it comes to politics, with women representing the most progressive sector of society, highly supportive of feminism, in contrast to a strong conservative turn among men of the same age. So how is a director to make a romantic comedy in times like these?

"This is not a simple romance movie" reads the remark that was voted to the top of Crazy Romance's viewer comments section on Naver.com. This is certainly true; I'm not even sure whether to classify the film as a romantic comedy or not. But its departure from the norms of the romance genre didn't do anything to limit its appeal. With close to 3 million tickets sold, it was one of the biggest hits of the fall season, and was widely praised by viewers for its sharp dialogue, and for nailing contemporary attitudes about relationships, work and sex.

"This is not a simple romance movie" reads the remark that was voted to the top of Crazy Romance's viewer comments section on Naver.com. This is certainly true; I'm not even sure whether to classify the film as a romantic comedy or not. But its departure from the norms of the romance genre didn't do anything to limit its appeal. With close to 3 million tickets sold, it was one of the biggest hits of the fall season, and was widely praised by viewers for its sharp dialogue, and for nailing contemporary attitudes about relationships, work and sex.

The protagonists of this film are in their 30s, and thus located between the My Sassy Girl generation and those currently in their twenties. Jae-hoon, who works in an advertising firm, is dealing with his ex-girlfriend's departure by drinking prodigious amounts of alcohol. This goes beyond the cute, drunken heartbreak we sometimes see in other romantic comedies -- Jae-hoon has a drinking problem, and often wakes up with no memory of what he did the night before. One morning he looks at his phone and realizes that late the previous night he spent two hours talking to Sun-young, who joined his company just the day before. It's an awkward situation, since he barely knows her, but seems to have confessed entirely too much to her on the phone. Then on his way to work, he happens to come across Sun-young in the midst of breaking up with her boyfriend. In this way, they start working together, already knowing a lot about each other's private lives.

Workplace culture, and the way personal life and work life often clash in awkward ways, is one of the themes of this film. Debut director Kim Han-kyul populates the office with a volatile mix of personalities, and the situations she presents accurately capture the range of stresses and frustrations that many young Koreans feel at work. After work hours, things only get more complicated, with Sun-young too showing a fondness for alcohol and a provocative streak.

Viewers should not expect the usual romantic trajectories in this film. Despite each of them being sensitive in different ways, Jae-hoon and Sun-young take what they need from each other, and don't seem too bothered by the fact that their relationship isn't clearly defined. Actors Kim Rae-won and Gong Hyo-jin are perfectly cast, particularly the latter, in that Gong's cool independence has always been one of her most appealing qualities as an actress. In a similar way, this film shows little interest in defining itself in terms of genre. In the end, this disregard for convention is one of Crazy Romance's strongest qualities. (Darcy Paquet)

This is a review of Jeon Gye-su's (Love Fiction) Vertigo, starring the currently hot, super-busy actress Chun Woo-hee (The Wailing, Idol, A Little Princess). First let me state my irritation for the film's title. To begin with, it is thoughtlessly lifted from one of the most famous movies ever made. For those who do not know Korean, "beotigo" roughly means "holding out," as in "I am holding out against all the awful things happening around me." So the title is a pun, but neither Korean nor English title in my view fits well with the film. Moreover, it renders searching for the movie in the internet rather cumbersome.

Seo-young, played by Chun, is a thirtysomething professional woman working in a corporation located in one of those high-rises in Seoul. Unlike the outwardly glamorous appearance, her life is constantly beset by crises and difficulties. Her job is only temporary and entirely dependent on the company's whim. Her clandestine romance with her superior Jin-su (Teo Yoo, Seoul Searching) is far from something stable either. Her relationship with her mother, who lives apart in Busan, is, charitably put, a mess, and one with her father, who had severed contact long time ago, is practically nonexistent. To add insult to injury, she has a chronic health issue.

Seo-young, played by Chun, is a thirtysomething professional woman working in a corporation located in one of those high-rises in Seoul. Unlike the outwardly glamorous appearance, her life is constantly beset by crises and difficulties. Her job is only temporary and entirely dependent on the company's whim. Her clandestine romance with her superior Jin-su (Teo Yoo, Seoul Searching) is far from something stable either. Her relationship with her mother, who lives apart in Busan, is, charitably put, a mess, and one with her father, who had severed contact long time ago, is practically nonexistent. To add insult to injury, she has a chronic health issue.

In short, she is an archetype of a Korean urbanite working woman in her thirties, into whose body and soul all the anxieties and pains of her cohorts are compressed. The film does not pull punches in illustrating the openly misogynistic corporate culture of Korea, almost to the point that it sometimes plays like a whistleblowing documentary. Physical forms of violence including sexual harassment are only a part of it. Perhaps even more frightening is the subtle structure of inequality underlying such brazen behaviors.

In a setup like this, the actor who plays Seo-young must carry the whole film like Atlas burdened with Earth on its shoulders, and Chun paints her portrait fervently, at times nearly majestically, as if she is a protagonist of a passion play. And she is extremely beautiful throughout the film. Someone quipped that this film is in effect a two-hour pictorial video showcasing Chun Woo-hee, but I think a pictorial that causes this much distress in the viewer would surely run into a problem.

Actually, the real problem with this film lies in its gazes toward Seo-young. It often appears to treat her pain and anxiety as objects of aesthetic appreciation. Like a heroine of a 19th century opera, Seo-young is beautiful precisely because she suffers. Indeed, is not the film giving greater weight to the pity the heroine's pain invokes, rather than her pain itself?

I believe Gwan-woo (Jeong Jae-gwang, Extreme Job), the film's "male protagonist," is the character that embodies this particular problem. For starters, he is a window-cleaner for the high-rise in which she works. Thanks to his job, Gwan-woo continues to observe Seo-young through the windows he is cleaning, and eventually she becomes aware of his eyes as well. If this set up had merely been a device to initiate a romantic relationship between the two, it might not have mattered much. However, in this film Gwan-woo's character literally consists of a collection of persistent voyeuristic gazes toward Seo-young. And I cannot help but recognize much overlapping grounds between Gwan-woo's actions and the film's objectification of Seo-young. To be blunt, this "man who pities a beautiful, suffering woman" takes up too much proportion of this film otherwise centered on the heroine.

This is one of the reasons why we flinch a bit when they manage to get together and start communicating with one another near the end. I do understand that the story was leading up to that moment, which is indeed dramatic and even beautiful, but if fails to convince as a real solution to Seo-young's problems. She is in fact deprived of the chances to reclaim her own life and actively wade out of the quicksand that it has become. Regarding this matter, I could not help but comparing Vertigo to Our Body, another film about a desperate thirtysomething Korean woman on the precipice. Yes, Ja-young in Our Body corners herself into a horrendous situation due to her ridiculous, uncontrollable desires, but her actions, self-destructive or not, are the outcomes of her own decisions. Seo-young, in contrast, has never had a real chance to properly exercise her free will.

I can only hope that Seo-young, after the movie has ended, will have found a proper legal solution to her troubles depicted in it. After all, she could subpoena a very persistent observer as her eyewitness. (Djuna, translated by Kyu Hyun Kim)

Over the past decade, few books published in Korea have made a bigger impact than the 2016 novel Kim Ji-young, Born 1982. The story does not seem at first glance to be out of the ordinary, centering around a woman who gets married and pursues a career before eventually becoming a stay-at-home mother and suffering from depression. But this ordinary quality is ultimately the point of the novel. Author Cho Nam-joo chose the name Kim Ji-young because it is the most common name among women of her generation, and the events of the book serve to illustrate the everyday discrimination and inequality faced by women as they go about their lives. Although novelists are often taught to bring their stories alive through specific details, Cho's decision to do the opposite ultimately manifests itself as a strong political statement.

Cho's novel is often described as controversial, but that statement needs a bit of clarification. The book was a huge bestseller, the only novel since Shin Kyung-sook's Please Look After Mom (2009) to top a million sales in Korea. Not only that, its subsequent publication in Japan and China was tremendously successful, signaling how much the story resonated in neighboring countries as well. Among most of the population, the book provoked discussion but not necessarily controversy. Nonetheless, South Korea does have highly reactionary, misogynist groups who revel in stoking mayhem online, and who found in Kim Ji-young, Born 1982 a easy target for their hate. So celebrities who admitted to having read the book, for example, found their social media accounts flooded by vicious comments.

Cho's novel is often described as controversial, but that statement needs a bit of clarification. The book was a huge bestseller, the only novel since Shin Kyung-sook's Please Look After Mom (2009) to top a million sales in Korea. Not only that, its subsequent publication in Japan and China was tremendously successful, signaling how much the story resonated in neighboring countries as well. Among most of the population, the book provoked discussion but not necessarily controversy. Nonetheless, South Korea does have highly reactionary, misogynist groups who revel in stoking mayhem online, and who found in Kim Ji-young, Born 1982 a easy target for their hate. So celebrities who admitted to having read the book, for example, found their social media accounts flooded by vicious comments.

Adapting the novel into a film resulted in a few predictable challenges. One was to deal with the expected backlash from anti-feminists, which may for example have affected the casting process. Fortunately, the very popular and talented Jung Yu-mi stepped forward to take the role, and she was joined by top star Gong Yoo (the two previously appeared together in Train to Busan and also the FEFF Audience Award-winning Silenced). But another predictable challenge involved the screenplay. How would the non-specific, slightly abstract nature of the novel translate into the highly specific medium of the cinema? In many ways it was a challenging novel to adapt for the big screen.

The film version of Kim Ji-young, Born 1982, helmed by actress-turned-director Kim Do-young, opened in October 2019. Both the online hate and the mainstream interest from female viewers turned out as predicted, with a very strong 3.7 million tickets sold. It ranks as the 7th-highest grossing Korean film of the year, and it also earned several acting honors for Jung Yu-mi from local film awards ceremonies.

To judge the film simply as a film, apart from the publicity surrounding its release, one can find in it both notable strengths and weaknesses. The lead performance is, in my opinion, the key strong point. Jung Yu-mi has a long history of bringing her characters to life in a way that few actresses can. Particularly because the main character is presented as having few unique qualities, it must have been a challenge to inhabit the role. Cinematically, it must be said, the film is somewhat plain in its presentation. The more complex structure of the novel, with flashbacks through various points of the main character's life, was also simplified in the adaptation. The end result, if a bit disappointing for some critics, nonetheless succeeded in creating both positive word of mouth and many new discussions around feminist issues. In that sense it's an important work of our time that will be remembered, even if it will never overshadow the novel. (Darcy Paquet)