2018

"Microhabitat", "Burning", "Drug King", "Little Forest"

The year 2018 was not a good year for blockbusters. With only a couple exceptions -- particularly Along with the Gods: The Last 49 Days, the sequel to the hugely successful Along with the Gods: The Two Worlds from the end of 2017 -- the films with the biggest budgets and most lavish marketing campaigns were forcefully rejected by audiences. Some of the most painful examples include Kim Jee-woon's dystopian Illang: The Wolf Brigade, Kang Hyeong-cheol's musical Swing Kids set in a POW camp, Kim Byung-woo's military thriller Take Point, Choo Chang-min's murder mystery Seven Years of Night, Yeon Sang-ho's Psychokinesis, Woo Min-ho's The Drug King, and Lee Jeong-beom's corrupt cop drama Jo Pil-ho: The Burning Rage. Every one of these were from directors who had enjoyed at least one major hit in the past.

The Korean film from 2018 that may be remembered the longest was also a commercial disappointment, but Lee Chang-dong's Burning received such a rapturous reception during its Cannes premiere and later international release that it no doubt ranks as the film of the year. A loose adaptation of a short story by Murakami Haruki, the film was by most measures a triumph.

In a commercial sense, the success stories from 2018 were the mid-budgeted films that enjoyed positive word of mouth among the audience. Some of the best-received films include Intimate Strangers, Believer (both remakes, incidentally), The Spy Gone North, Default, coming of age story On Your Wedding Day and the rural drama Little Forest. Independent cinema enjoyed a strong year as well, with numerous standouts including Microhabitat, Last Child and After My Death.

Reviewed below: Psychokinesis (Jan 13) - Little Forest (Feb 28) - The Vanished (Mar 7) - Be With You (Mar 14) - Microhabitat (Mar 22) - Seven Years of Night (Mar 28) - Gonjiam: Haunted Asylum (Mar 28) - True Fiction (Apr 25) - Believer (May 22) - Illang: The Wolf Brigade (Jul 25) - The Spy Gone North (Aug 8) - Last Child (Aug 30) - Monstrum (Sep 12) - The Great Battle (Sep 19) - Intimate Strangers (Oct 31) - Unstoppable (Nov 22) - Default (Nov 28) - Door Lock (Dec 5) - Swing Kids (Dec 19).

| Korean Films | Nationwide | Release | Revenue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Along with the Gods: The Last 49 Days | 12,275,843 | Aug 1 | 102.7bn |

| 2 | The Great Battle | 5,441,020 | Sep 19 | 46.3bn | 3 | Intimate Strangers | 5,294,119 | Oct 31 | 44.4bn | 4 | Believer | 5,063,684 | May 22 | 43.5bn |

| 4 | The Spy Gone North | 4,974,520 | Aug 8 | 42.8bn |

| 5 | Dark Figure of Crime | 3,789,321 | Oct 3 | 33.0bn |

| 6 | Default | 3,754,732 | Nov 28 | 30.9bn |

| 7 | Keys to the Heart | 3,419,753 | Jan 17 | 27.5bn |

| 8 | The Witch: Part 1. The Subversion | 3,189,091 | Jun 27 | 27.2bn |

| 9 | The Accidental Detective 2: In Action | 3,152,872 | Jun 13 | 26.9bn |

| 10 | On Your Wedding Day | 2,820,969 | Aug 22 | 23.7bn |

| All Films | Nationwide | Release | Revenue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Along with the Gods: The Last 49 Days (Korea) | 12,275,843 | Aug 1 | 102.7bn |

| 2 | Avengers: Infinity War (US) | 11,212,710 | Apr 25 | 99.9bn |

| 3 | Bohemian Rhapsody (US) | 9,923,791* | Oct 31 | 86.1bn |

| 4 | Mission: Impossible - Fallout (US) | 6,584,915 | Jul 25 | 55.9bn |

| 5 | Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (US) | 5,661,128 | Jun 6 | 49.8bn |

| 6 | Ant-Man and the Wasp (US) | 5,448,134 | Jul 4 | 47.5bn |

| 7 | The Great Battle (Korea) | 5,441,020 | Sep 19 | 46.3bn |

| 8 | Black Panther (US) | 5,399,227 | Feb 14 | 45.9bn |

| 9 | Intimate Strangers (Korea) | 5,294,119 | Oct 31 | 44.0bn | 10 | Believer (Korea) | 5,063,684 | May 22 | 43.5bn |

* Includes admissions from 2019. Revenue is in Korean currency (US$1=~1200 won).

Source: Korean Film Council (www.kobis.or.kr).

Seoul population: 9.8 million

Nationwide population: 51.8 million

Seok-heon (Ryu Seung-ryong, Seven Years of Night) works as a security officer at a small bank branch office. Not exactly the most reliable person in the neighborhood, he one day drinks stream water at a mountain park, and imbibes the fluorescent-blue substance that had just landed in a meteor from outer space. Pronto, Seok-heon becomes imbued with psychokinetic powers, able to first lift a lighter and a box of matches without touching them, then to fly through the air and crush an automobile like a gigantic vise. Crass and inconsiderate, he instantly hatches a scheme to haul bucket-loads of dough as Korea's new David Copperfield, until he learns that his divorced wife died in a suspicious circumstance. She suffered a fractured skull fighting off corporate-employed thugs trying to evict his daughter Rumi's (Shim Eun-gyeong, Miss Granny) successful fried chicken restaurant from a building purchased for redevelopment. Seok-heon reluctantly becomes a human weapon against the company thugs to help his straight-laced daughter, but neither the law nor the media is willing to buy his story that he is some kind of a homespun superhero.

Yeon Sang-ho, after dominating the 2016 summer box office with the zombie blockbusters Train to Busan and Seoul Station, has returned to a SF fantasy subject matter. He also switched the tone to emphasize comedy and slapstick, even though a certain level of anti-social impulse from his previous films is retained. The motion picture, distributed outside of Korea by Netflix, was panned by critics and internet wags but managed to collect approximately 980 thousand tickets, a middling score for a domestic genre film.

Yeon Sang-ho, after dominating the 2016 summer box office with the zombie blockbusters Train to Busan and Seoul Station, has returned to a SF fantasy subject matter. He also switched the tone to emphasize comedy and slapstick, even though a certain level of anti-social impulse from his previous films is retained. The motion picture, distributed outside of Korea by Netflix, was panned by critics and internet wags but managed to collect approximately 980 thousand tickets, a middling score for a domestic genre film.

Taking into account the fact that South Korean film industry is not particularly adept at any kind of science fiction-inflected narrative, Psychokinesis is not badly made. Of course, those expecting something on the order of Spider-man: Homecoming or Thor: Ragnarok should scale down their expectations. Yeon is not particularly good with Hollywood-style CGI effects (the flying sequences are embarrassingly cut-rate), but there are scenes in which the physical effects combined with elaborate stunt action (supervised by Heo Myung-haeng and Jeong Jin-geun of the Seoul Action School) generate the desired emotional reaction from the viewers. Ryu Seung-ryong has been accused of being too goofy in his scenes of exerting himself to dredge up his psychokinetic powers (he looks ready to poo in his pants), but I did not find them particularly annoying: those things in many ways come with the territory. And there are plenty of dumb stuff going on in multi-hundred-million-dollar Hollywood projects like Guardians of the Galaxy or Green Lantern, too. Think of it as a contemporary, faster-paced, East Asian take on The Greatest American Hero TV series (they share the scenes of the protagonist pawing the air trying to fly expertly like, you know, Superman) then you got the right groove.

Actually, the biggest problem I had with Psychokinesis was neither the movie's openly playful tone, Yeon's direction (which is reassuringly competent, if not always creative as in his better works) nor the level of technical expertise, but his insistence that this film should be yet another (groanˇ¦) "redemption narrative" for a bum dad. For me, the movie would have worked many times better (and probably reached out to a larger share of domestic viewers) if Shim Eun-gyeong's Rumi (or at the very least, her fussy-nice lawyer friend Jeong-hyun [Park Jeong-min, Dongju: The Portrait of a Poet]) was the one endowed with superpowers. Why does her father, who had not displayed a shred of concern for her life before the movie begins, have to be the one with these abilities? So that the viewers could tear up seeing him learning the hardship his child had to put up with, and ultimately transforming himself into a politically conscious anti-chaebol activist? Even though this "paternal redemption" story is essentially the same narrative engine that propelled Train to Busan, that film had a bunch of truly interesting supporting characters and layers of story elements brilliantly orchestrated by the director. Psychokinesis, much simpler and linear in plot, is deprived of this support structure.

Casting Ryu Seung-ryong in the role of the father only compounds the problem. Again, I have little problem with the actor, who is certainly one of the more earnest character actor-stars working in Korea today (and superb in such subtler roles as the minister in Masquerade [2011] and the conflicted detective in Possessed [2009]). But the character of Seok-heon is frankly a callous scoundrel, and Ryu, looking like a bull-hound with a bad stomach problem, cannot project any charm or sociable qualities. He merely acts very hard, (his comic acting, I reiterate, is not as terrible as internet critics are blasting about) but is ultimately defeated by the shallow characterization.

Indeed, it is a sign of a talented filmmaker stuck with a stale conception of the "good guys" in a story of good-triumphs-over-evil, when the villains of the piece-- "president" Min (Kim Min-jae, The Truth Beneath), the boss of the service company (read: thugs) hired by the big business executive Deputy Hong (Jeong Yoo-mi, Our Sunhi)-- come across as more attractive, even more charming, than the protagonists. Ms. Hong, the head villain, is actually the most interesting, if not the most complex, character in the whole movie. Quite pretty and mad as a hatter, she is an intriguing combination of a Gangnam-style, chi-chi superficiality and a deeply sociopathic ego, a sort of merrily chatty female version of Ernst Stavro Blofeld. It was an inspiring move on Yeon's part to cast the beautiful but off-kilter Jeong as Deputy Hong. Her reaction to Seok-heon smashing her BMW and flying out of the police station is priceless: it would have been great if the movie contained more character-driven funny scenes like that.

Psychokinesis is not a terrible film: I can think a number of ways in which it could have gone much worse (insisting on being dourly "serious" would certainly have been one of them). On the other hand, it is demonstrably less powerful or creative than Yeon's previous works. I have enjoyed the movie for what it is, a middling SF fantasy with a light tone (most clearly exemplified by a silly TV-commercial-style denouement). I strongly suggest to Yeon that, however, he should write his next movie around the non-victimized characters playable by Shim Eun-gyeong or, for that matter, Jeong Yoo-mi (I certainly wouldn't mind seeing Deputy Hong come back as a supervillain!). No more redemption narratives for bum fathers, please. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

When Hye-won decides to abandon the city, it may seem at first like she's running away. She's certainly going to a remote place - her childhood home is in a tiny farming village, completely cut off from the fast-paced, urban lifestyle that epitomizes South Korea. The house itself is empty. And for a woman in her twenties, there doesn't seem to be much to do there, except grow food on the land surrounding the house, and cook with whatever ingredients can be harvested. It's subsistence living, dictated by nothing more than the changing of the seasons.

She's not completely alone there. There's her elderly aunt, who lives in another part of the village. There's a dog named Ogu, adopted by Hae-won (or vice versa). And there are two childhood friends - Jae-ha who grows fruits and vegetables, and Eun-sook who commutes to a nearby town to work as a bank teller. The three rekindle their old camaraderie, filled with intimacy and tension, made stronger by the fact that in this remote place, they only have each other.

She's not completely alone there. There's her elderly aunt, who lives in another part of the village. There's a dog named Ogu, adopted by Hae-won (or vice versa). And there are two childhood friends - Jae-ha who grows fruits and vegetables, and Eun-sook who commutes to a nearby town to work as a bank teller. The three rekindle their old camaraderie, filled with intimacy and tension, made stronger by the fact that in this remote place, they only have each other.

Hye-won often invites them to her home to share in the meals she prepares. She is an imaginative and proficient cook, having learned from her mother. Indeed, cooking became more of a necessity for her when, during her last year in high school, her mother abruptly left home. Years later, Hae-won is still recovering from this abandonment, even after growing up and becoming independent. And the cooking she does, suffused with old memories, is in part a way to work through her complicated feelings about her mother.

Little Forest is not a typical film. Honestly, it's just a wisp of a story, with much of its running time devoted to cooking and conversation. Nonetheless, it leaves its audience feeling full. Partly this is due to it being so well made: director Yim Soon-rye (Waikiki Brothers, Forever the Moment) has over two decades of filmmaking experience, and she's more than capable of instilling ordinary moments with life and meaning. As for the acting, Kim Tae-ri (who became an instant star in Park Chan-wook's The Handmaiden) perfectly embodies the blend of independence and unpredictability that defines Hye-won's character. She's joined by Ryu Jun-yeol (A Taxi Driver), one of Korea's most exciting up-and-coming male actors; the acclaimed Moon So-ri (The Running Actress), who brings an enigmatic quality to the flashback scenes with Hye-won's mother; and talented newcomer Jin Ki-joo as the temperamental, flirtatious Eun-sook.

Little Forest is based on a Japanese manga by Igarashi Daisuke, and some viewers may know a four-hour Japanese adaptation of this book, which begins in the summer, and has an hour devoted to each season. That 2014 work is in some ways even more minimal, with its story structure determined not by plot twists, but by the seasonal ripening of fruits and vegetables. I myself am a committed, rabid fan of that Japanese movie, and so as much as I was looking forward to this Korean adaptation, I was also bracing myself for disappointment. But ultimately it was a pleasure to discover that Yim Soon-rye's version has its own particular strengths and concerns, and there's no real need to compare the two films.

Released in February, Little Forest had a surprisingly strong run at the box office, and captured the imagination of younger viewers in particular. Nonetheless, I think if it had been released a decade earlier, it might have struggled to find an audience. One senses a shift of attitude among young Koreans these days. Faced with an ever more competitive and stress-filled lifestyle, in crowded cities with polluted air, and with career goals that often lead to frustrating dead ends, the emergence of a film with values so fundamentally opposed to the norm brought a breath of fresh air. In a word, this is the kind of film to make you consider quitting your job, and leaving the city behind. (Darcy Paquet)

Dr. Park Jin-han (Kim Kang-woo, Tabloid Truth), a research scientist working for a big pharma company, has recently lost his older wife Seor-hee (the veteran TV actress Kim Hee-ae) to a heart failure. However, the latter's body disappears from the morgue in the National Forensic Service building, under a strange, possibly supernatural circumstance. Dr. Park, summoned to the morgue, is detained, to his consternation, by the disheveled detective Joong-sik (Kim Sang-gyung, The World of Silence) and his team, despite lack of any physical evidence that the former was involved in stealing or hiding the body. It turns out that our good doctor had been carrying on an affair with a college student Hye-jin (Han Ji-an) and used his newly developed medication that suppresses activities of the central nervous system, mixed into a glass of wine, to murder his wife. As the night progresses, Dr. Park begins to suspect that Seor-hee has somehow survived the assassination attempt, and is now seeking revenge by framing him for her own murder, or worse.

The Vanished is a remake of the Spanish mystery thriller The Body (2012), directed by Oriol Paulo, the hand behind the superb, classically-inflected whodunit The Invisible Guest (2017). The newcomer co-writer-director Lee Chang-hee (the other screenwriter is Lee Hee-chan, Run-off) is obviously a fan of the genre. He follows the original's plot rather closely, keeping the clues add up without ladling the Korean-style melodramatic conventions (until the climax, that is, to which I will come back shortly) on them. The movie initially does not inspire much confidence when it starts out like an antiseptic variant of Ju-On, but once latched onto the groove of the central mystery, it makes for a reasonably compelling viewing. Director Lee deploys the production team, spearheaded by the DP Lee Jong-yeol and Lighting Supervisor Jang Tae-hyun, to keep the visuals clean-cut, devoid of meaningless clutter, and emphasizing metallic anxiety creeping up on the main characters as well as their cold calculation. The dialogue is peppered with technical terms (forensic, pharmaceutical and otherwise) not always explained. Overall, the aura of a technically authentic mystery is carefully maintained, although some surrealistic visuals indicating subjective experiences and emotions of the characters are furtively inserted in a few sections.

The Vanished is a remake of the Spanish mystery thriller The Body (2012), directed by Oriol Paulo, the hand behind the superb, classically-inflected whodunit The Invisible Guest (2017). The newcomer co-writer-director Lee Chang-hee (the other screenwriter is Lee Hee-chan, Run-off) is obviously a fan of the genre. He follows the original's plot rather closely, keeping the clues add up without ladling the Korean-style melodramatic conventions (until the climax, that is, to which I will come back shortly) on them. The movie initially does not inspire much confidence when it starts out like an antiseptic variant of Ju-On, but once latched onto the groove of the central mystery, it makes for a reasonably compelling viewing. Director Lee deploys the production team, spearheaded by the DP Lee Jong-yeol and Lighting Supervisor Jang Tae-hyun, to keep the visuals clean-cut, devoid of meaningless clutter, and emphasizing metallic anxiety creeping up on the main characters as well as their cold calculation. The dialogue is peppered with technical terms (forensic, pharmaceutical and otherwise) not always explained. Overall, the aura of a technically authentic mystery is carefully maintained, although some surrealistic visuals indicating subjective experiences and emotions of the characters are furtively inserted in a few sections.

The performances are okay to good. Kim Kang-woo is pretty well cast as an elite intellectual who, despite the practiced air of arrogance and nonchalance, soon finds himself out of his depth. Kim Sang-gyung, on the other hand, presented as an Akechi Kogoro-Lieutenant Columbo type, is closer to a typical Korean detective character in the sense that there is little hint that his uncouth countenance and vulgar behavior are masking a sharp intelligence or a superior power of observation. At least his sob-story background, a terrible cliché of its own, is organically tied to the film's central mystery of the missing body. It is too bad Lee could not have reconceived the whole story with Seor-hee and Hye-jin at the forefront rather than these two male leads: Kim Hee-ae in particular has a few decent set pieces in which she gets to show off the icy authority of a woman who cannot imagine having her opinions questioned.

I enjoyed watching The Vanished, its hackneyed characterization and other problems notwithstanding, up to the big climax. At that point, the movie unfortunately goes into an automatic drive and 1) begins to show a tiresome montage of "this is really what happened," with that "poignant" um-cha-cha um-cha-cha waltz music copied from the Oldboy score (the variants of which should be permanently banned from all Korean crime-mystery-horror-thrillers henceforth) in the background, 2) that involves yet another hit-and-run car accident as the crucial plot point (which also should be banned from all Korean crime-mystery-horror-thrillers. Do the Korean drivers in movies ever put on brakes when people walk into their paths? On the second thought, considering the I'd-rather-die-in-a-horrible-crash-than-be-five-minutes-late way they drive in real life, perhaps this is realism), and 3) ends with another "poignant" shot of a necklace (or a pendant, or a ring, or a fountain pen, or a handkerchiefˇ¦ so on and on) shakily held by a character. The plot of The Vanished cries out for the kind of dry, thoughtful resolution that tests our acknowledgement of the limits of the rational justice system: knowing that this is a South Korean film, you could be rest assured that such an ending does not materialize. I am not even going to talk about the loose threads left hanging at the end, which, as I recollect, The Body, the original, was not exactly free from either.

The Vanished is one of those recent South Korean mystery thrillers, competently made and attractively lensed, that nonetheless never really push the envelope, much less break through it. In the early part of the movie, a psychiatrist tells Joong-shik, "You are just working out your resentment of the 'haves.'" Turns out it is all that the movie has to say, too, that the 'haves' will get away with anything (and we are supposed to be hopping mad about it). Like horror, a good mystery thriller ought to be able to speak about the things- including the truths that challenge social conventions and political designs masquerading as self-evident morality- that a hectoring conspiracy thriller or a cop-busts-psycho-killer kind of exploitation nonsense cannot. Every once in a blue moon we get a film, like, say, The Truth Beneath, that actually does that or at least aspires to do so. It is hoped that director Lee's next film would jump the hurdle and sprint toward that direction. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Woo-jin is a single father living with his elementary school-aged son in a small town, working as a janitor at the town swimming pool. Each morning as they leave their home, they plant a kiss on a photo that hangs by the door, showing the two of them with the boy's deceased mother, Soo-ah. Both Woo-jin and his son desperately miss Soo-ah, who passed away the previous year. But just as the rainy season starts, a miracle happens.

From an abandoned train tunnel, Soo-ah re-appears, looking just as she did before her untimely death. She seems to recognize Woo-jin, but she has no memory of her life spent with the two of them. Confused but overjoyed, they take her home and the three of them start to live together once more. For Soo-ah, it is as if getting to know them for the first time. For the boy and his father, it is a deep, healing joy that washes away their grief, but they both suspect that her time with them may be temporary.

Be With You is based on a Japanese novel by Ichikawa Takuji, which in turn was made into a 2004 film by Doi Nobuhiro. Both the novel and the film won over many fans in Korea, so it was a smart move to re-adapt this story for a new generation of Korean viewers. Debut director Lee Jang-hoon proved fortunate in his casting as well, landing not only the popular film and TV star So Ji-sub (showing a very different side of himself than he did in Ryoo Seung-wan's The Battleship Island), but also the queen of melodrama herself, Son Ye-jin.

Be With You is based on a Japanese novel by Ichikawa Takuji, which in turn was made into a 2004 film by Doi Nobuhiro. Both the novel and the film won over many fans in Korea, so it was a smart move to re-adapt this story for a new generation of Korean viewers. Debut director Lee Jang-hoon proved fortunate in his casting as well, landing not only the popular film and TV star So Ji-sub (showing a very different side of himself than he did in Ryoo Seung-wan's The Battleship Island), but also the queen of melodrama herself, Son Ye-jin.

Son Ye-jin is an absolute pro, and it's no criticism of the other actors to say that Soo-ah outshines everyone else in the film. Despite being curiously passive for much of the running time (for reasons that become clear in the surprising reveals that emerge in the second half), Son carries the role with her presence, never expressing more than she needs to. The other actors tune their performances to hers, making the scenes with her feel natural and genuine.

The genre of melodrama used to be a pillar of Korean cinema, so much so that it was a key part of the industry's identity. But over the years, as investors and studios switched their allegiance to thrillers and social dramas, melodramas have fallen by the wayside. Simultaneously, the explosive growth of the Korean TV drama sector, where melodrama is king, has left film melodrama looking displaced. One might fault filmmakers for not developing their own, distinct style to distinguish film from TV melodrama. But clearly, there is still interest in such works among the theatergoing audience. Sure enough, Be With You opened at #1 at the box office and showed unusual staying power, resulting in a profitable run.

Be With You is not without its weak points (I'm not sure I will ever find it in my heart to forgive Woo-jin's pink jacket... those who see the film will know what I'm talking about). But in its intricate web of flashbacks, reunions, tears and revelations, it builds towards an emotional and satisfying conclusion. It will certainly not appeal to viewers who actively dislike melodrama, or to cynics. But for those more open to the genre's charms, it is a safe recommendation. (Darcy Paquet)

Moving to Japan for family reasons in 2017 has resulted in a major change in my film-watching habits. Basically, I don't have any such habits anymore. I've drastically dwindled down from around 150 movies in theaters to maybe, if I'm lucky, 10. There are many reasons for this drastic drop—my significantly reduced income, vacation, and free time since the average worker in Japan works inhumane hours and is paid poorly (but thankfully has fairly affordable national healthcare and, in the large cities, transportation); my lack of linguistic access to films since learning to read Japanese has been painstakingly slow and my Korean has always been poor; and my self-limiting preference to experience film in a theater rather than on a TV or computer screen. All of this contributes to the hilarious irony that I have been writing here at Koreanfilm.org since 2000 documenting many lesser seen gems of South Korean cinema in hopes of influencing wider notice in the US and elsewhere, yet once the US finally acknowledges the South Korean film industry through the multiple awarding of Bong Joon Ho's Parasite, I still have yet to see that very film that culminates all the work I and many others have done. I've "watched" Parasite in that I watched the film on New Year's day 2020 here in a Toho Cinema in the Hibiya neighborhood of Tokyo, but with Japanese subtitles. The problem is I haven't had the benefit of truly "seeing" it since most of the dialogue was lost to me without the accessibility of Darcy's English subtitles in the version released in places like my home country. (I knew enough to catch the dialect shift to North Korean in the film, at least.)

In March 2022, I finally came around to getting one of those contraptions that turns your TV into the internet. My wife had convinced me that we should subscribe to Netflix rather than continuing to participate in the less cost effective ritual of maintaining a relationship with our neighborhood corporate DVD rental store. (This was originally a Tsutaya, but after that closed down, we shifted to Geo, pronounced 'Gay-oh', not 'Jee-oh'.). Sadly, the Korean films on Netflix geo-curated here are either the type I'm not really that interested in or they are only subtitled in Japanese. As a result of the latter, I still can't see Parasite.

In March 2022, I finally came around to getting one of those contraptions that turns your TV into the internet. My wife had convinced me that we should subscribe to Netflix rather than continuing to participate in the less cost effective ritual of maintaining a relationship with our neighborhood corporate DVD rental store. (This was originally a Tsutaya, but after that closed down, we shifted to Geo, pronounced 'Gay-oh', not 'Jee-oh'.). Sadly, the Korean films on Netflix geo-curated here are either the type I'm not really that interested in or they are only subtitled in Japanese. As a result of the latter, I still can't see Parasite.

But in addition to Netflix, we downloaded the free service TUBI owned by the democracy-destroying Fox corporation. And in spite of how they are bringing my country closer and closer to fascism, turns out TUBI has a few fairly good South Korean film selections, particularly one I've been wanting to see for some time—Jeon Go-woon's Microhabitat. Yet that access was temporary. When attempting to see Microhabitat a second time to refine my recall of the plot for this film essay, I discovered a message telling me now that TUBI is not available in my region. Down, down, down like a Bong film goes the irony upon irony upon irony.

My inability to watch the film a second time leaves me unsure of the narrative trajectory. I am at the mercy of Wikipedia, a website that still refuses to spell Hong Sangsoo's and Bong Joon Ho's names correctly. (Wikipedia's arrogant editors are quite resistant to such a change, offering up excuses that expose their ignorance about Korean cinema.) Unfortunately, plot points important to my discussion of the film are missing from Wikipedia's summary. (As of January 17th, 2023, there is no mention of the sex worker who plays a significant role in the movie.) So if I mess-up on some of the chronology of events, my apologies, but this also becomes an example of how we remember films in ways that are "incorrect". Sometimes how we mis-remember films results in a need to change our arguments. Sometimes chronology matters. Other times it doesn't. I think this is one of those latter times where time has no impact on meaning.

Microhabitat follows Mi-so (Esom, The Last Blossom, Samjin Company English Class). Mi-so is a housekeeper and a cleaning lady for a salon. Because her valuable labor is devalued through its feminization and failure to extract wealth from other laborers, she is not paid a living wage. When her rent is increased along with the tax that impacts one of her primary joys and sources of anxiety-reduction, cigarettes, she has to make a decision. (Whiskey is important to her as well, but not in a need to get drunk, more like the aesthetic joys of drinking good whiskey in a bar, similar to the joy I find when drinking coffee in coffeehouses or Japanese kissatens.)

American Republicans like Mitt Romney would tell Mi-so to ask her uncle for a $20,000 interest-free loan. But Mi-so has no family to buffer her for even $20. She did have a network of friends from college, free-spirited bandmates. (Something I can't verify is whether Mi-so may have not been able to finish college due to financial problems, but I think that was the case.) As for her boyfriend, he can't house her because he lives in an all-male dormitory that his factory employer subsidizes. Since the employer controls the key chains, she cannot live there. All told, Miso is a member of the enlarging precariat class where certain life happenings result in one falling quickly into insurmountable poverty. Considering her financial limitations, Mi-so makes a decision to tap into her friendship network to see who can temporarily house her until her life becomes less precarious.

Although almost all of her crew are delighted to see Miso—the only male band member is too depressed to express delight about anything—they have each ventured onto life paths that have distanced themselves from the plight Mi-so has found herself in. We meet a friend who has to hook herself up to an IV drip to survive the inhumane demands of corporate life. We meet a friend who lives a suffocating life with her in-laws. We meet a man whose wife committed him to an expensive lease of a condo only to leave him soon after. We meet a woman who married 'right', now living in opulent splendor.

Mi-so is able to empathize with all of her friends' various situations, yet they don't appear to possess the capacity to empathize with her. This is perhaps because she is what they fear for themselves, a loss of financial capital that results in the loss of social capital that prohibits one from climbing back into ones previously held social standing. This is most prominently displayed in her final friend visit where they eat at either end of a long royal table, disallowing the physical closeness that enables emotional connection. It's as if in some ways Mi-so's friend doesn't want to get too close to Mi-so, or else the social filth of Mi-so's predicament will rub-off on her.

Mi-so is able to empathize with all of her friends' various situations, yet they don't appear to possess the capacity to empathize with her. This is perhaps because she is what they fear for themselves, a loss of financial capital that results in the loss of social capital that prohibits one from climbing back into ones previously held social standing. This is most prominently displayed in her final friend visit where they eat at either end of a long royal table, disallowing the physical closeness that enables emotional connection. It's as if in some ways Mi-so's friend doesn't want to get too close to Mi-so, or else the social filth of Mi-so's predicament will rub-off on her.

This is why it's interesting that the Wikipedia plot summary excises the sex worker character because Mi-so's relationship with the sex-worker is so important to laying out the kind of person Mi-so is. Somewhere in the chronology Mi-so meets a customer at the salon where she worked who is presented to be an escort or hostess club worker. Mi-so begins cleaning that woman's fancy apartment, making more money as a result. Eventually Mi-so's benefactor loses her own benefactor at some point, making her financially incapable of continuing to employ Mi-so. Yet unlike her bandmates, Mi-so refuses to socially distance herself from the sex-worker. She isn't worried about the social 'taint' that might rub off on her because she doesn't perceive the sex workers work as 'tainted'. Mi-so works in dust and dirt and grime and grease and piss and shit. She understands all is part of life and ones proximity to it should not define ones value.

As a result, Mi-so empathizes with her now former benefactor's plight. Mi-so does not get angry at her. Mi-so understands the choices that societies like South Korea pressure folks to make in order to survive financially, especially for women. Mi-so's final richly married friend is particularly upset with Mi-so mentioning the friend's 'wild' past, which implied consensual sexual pleasure. Mi-so's friend is worried her husband will jettison her because of the 'stain' of being associated with a woman who actually chose to engage in freely-chosen pleasure prior to meeting him. If he does dismiss her due to his misogynistic mannerism about manners, Mi-so's friend might lose all the financial and social capital she's built up via beliefs and contracts that have left someone like Mi-so in such a precarious predicament. It is this secret revealed that causes Mi-so's friend to lash out at Miso. It's as if she is saying, 'Why don't you lie for me?! Why don't you at least lie through omission so I can stay in my social position?!' Mi-so's friend kicks her out of her house just as Mi-so's friend has kicked out her past to maintain her present and bring about her future. Mi-so's friend's treatment of Mi-so is in stark contrast to Mi-so's treatment of the sex worker. Unlike her social distancing dining table friend, Mi-so identifies with the sex worker. The sex worker's plight is Mi-so's plight. The sex worker's precarity is Mi-so's precarity.

In spite of what I might be mistaken about the plot thanks to not having access to a second viewing, and in spite of my only having access to watching the film Parasite but not having accessing to seeing it, Jeon's micropiece is an interesting film to parallel with Bong's masterpiece. Bong has always placed certain characters down into deeper dwellings. The wide reception of Parasite led many news outlets to elaborate on the significance of banjiha, what such cheap basement housing is called in South Korea and which were frightening deathtraps for so many during the floods in the summer of 2022 resulting in federal legislation to outlaw them. As Julie Yoon reported for BBC Korean in an article on February 10th, 2020, banjiha get "so little light that even [a] little succulent plant couldn't survive." That quote resonates metaphorically to the poor economic state of those who reside in banjiha, as does the downward direction into the unknown of precariat lives that was the Parasite secret cellar dwelling.

But director Jeon goes upward, causing confusion with the standard up-down metaphor. While looking for a cheaper apartment, Mi-so has to walk up more and more flights of steps to reach fewer and fewer affordable housing units. This physical upward trajectory is counter to our usual downward trajectory that Parasite easily situates. And not only that, there is a great deal of counter-metaphor regarding the idea of growth. In Microhabitat, it's not a life-giving plant, but life-threatening black mold. The final dissonance is provided by the fact that these apartments reaching for the sky are as dark as the dwellings digging into the ground. The only typically congruent metaphor director Jeon provides is the fact that these upper dwellings lack reliable power—literally electrical, but also metaphorically financial and social.

But director Jeon goes upward, causing confusion with the standard up-down metaphor. While looking for a cheaper apartment, Mi-so has to walk up more and more flights of steps to reach fewer and fewer affordable housing units. This physical upward trajectory is counter to our usual downward trajectory that Parasite easily situates. And not only that, there is a great deal of counter-metaphor regarding the idea of growth. In Microhabitat, it's not a life-giving plant, but life-threatening black mold. The final dissonance is provided by the fact that these apartments reaching for the sky are as dark as the dwellings digging into the ground. The only typically congruent metaphor director Jeon provides is the fact that these upper dwellings lack reliable power—literally electrical, but also metaphorically financial and social.

Jeon's film also lacks physical violence. The violence of Korean films and the TV show Squid Game has delighted Western viewers so much that violence is how many Westerners primarily imagine Korean films. As the borderline sociopathic fund manager Bobby Axelrod (Damian Lewis, Romeo & Juliet, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood) says in one episode of season two during a discussion about destroying a small town by imposing the financial violence of austerity measures, "We'll be gutting them for their organs, like in a Korean horror movie." The violence Mi-so experiences in Microhabitat is a similar financial violence to the one Axelrod wields, the everyday microaggressions of poverty, a poverty clearly feminized. This is one of the many points where Microhabit resonates with the greatest South Korean film ever made—not Parasite, but Jeong Jae-eun's Take Care of My Cat.

Interestingly, whereas Microhabitat differs distinctly in metaphor from the globally popular Parasite, Microhabitat also differs slightly from its fore-mother Take Care of My Cat in its elliptical non-resolution. (That's a spoiler alert if you need one.) Mi-so doesn't have a financially privileged Tae-hee to help her leave her predicament by leaving South Korea as Ji-young did in Take Care of My Cat. Mi-so is left with her own drastically limited devices to camp out and survive and see what might happen should her boyfriend return from his transfer to the Middle East and should either be able to find each other in a place where a new life might be possible. Take Care of My Cat and many films at the time it was made had Korean women leaving South Korea to evade sexist barriers. Microhabitat follows a woman who has no means to leave the political island she is trapped within.

Please understand that my contrasting Microhabitat here is not meant as a passive-aggressive way to slam Parasite. I love Bong Joon Ho! Unlike Wikipedia, I respect the guy. I spell his name right. As far as I can tell, not being able to "see" it, Parasite is a great film, a film worthy of all the awards it received. I mean, come on, Song Kang-ho is in it, making it great by default.

But the clear difference in the distribution and reception of Microhabitat versus Parasite in Western worlds reminds me of the hope I had as an earlier observer of South Korean film. I was struck by South Korean films for many reasons. If you know one of the directors I focus on, Hong Sangsoo is a major influence. But there was another big influence. Although I appreciated the operatic violence of films like Nowhere to Hide, I didn't stay with South Korean cinema for the spectacle of splatter in films like Shiri or Oldboy. A big part of why I stayed for the eventual ride to global popularity were the feminist struggles of the great triumvirate of women directors, Byun Young-joo, Yim Sun-rye, and the aforementioned Jeong. They were touching on aspects of Korean societies that resonated with aspects of my American societies along with making sure I understood the differences from the macro in the micro-worlds of various Korean women.

But the clear difference in the distribution and reception of Microhabitat versus Parasite in Western worlds reminds me of the hope I had as an earlier observer of South Korean film. I was struck by South Korean films for many reasons. If you know one of the directors I focus on, Hong Sangsoo is a major influence. But there was another big influence. Although I appreciated the operatic violence of films like Nowhere to Hide, I didn't stay with South Korean cinema for the spectacle of splatter in films like Shiri or Oldboy. A big part of why I stayed for the eventual ride to global popularity were the feminist struggles of the great triumvirate of women directors, Byun Young-joo, Yim Sun-rye, and the aforementioned Jeong. They were touching on aspects of Korean societies that resonated with aspects of my American societies along with making sure I understood the differences from the macro in the micro-worlds of various Korean women.

It was the feminist takes that I very much tried to highlight as a reason that South Korean films were worthy of greater consideration before Tarantino and Harry Knowles got their intersecting fan boys to drool over the blood dripping in other South Korean films. So it is with great irony that I return to Koreanfilm.org after a long absence caused by life changes limiting my access to the South Korean films I want to see. Microhabitat is the film I wanted to take care of when writing about Korean cinema. But now I have less of an ability to do that.

Thankfully, South Korean cinema doesn't seem to need me any more. (I recognize that is an arrogant, Columbus-ing statement. South Korean cinema never needed me. It did fine on its own terms.) Microhabitat is part of a new South Korean weave of women-directed films that I've been hearing about, films like the houses of us and hummingbirds, the Chan-sil's and Kim Ji-young's, all films expertly chronicled by other writers, such as on our website here by Rachel Min Park or in a wonderful film essay on South Korean women directors by Hieu Chau and Natalie Ng on the Australian film website Film In Ether. I just wish I could do more than just hear about them, than just watch them pass me by. I do hope I can see them, read them in a language I know, feel the bright pulse of the light from the screen of a darkened movie theater, a haptic tactic I've found affords greater empathy and brings me towards a more profound understanding than the emotional distance I feel with my TV.

The irony digs deeper knowing I am very much at a place in my life when these #DirectedByWomen Korean films are a sustenance I greatly need, yet I am less able to access these films that nourish me more than films by men that hammer and pummel and bruise. Don't worry, I still have other mediums that provide that sustenance. I still have access in Japan to books and so many delightful coffee houses in which I can read those books like Mi-so savors her whiskey and cigarettes at bars. It's just that I no longer have the rituals of my church of cinema where I prefer to practice my praxis. I miss cinema. But I will move on to other smaller spaces that provide similar solace, knowing solace is savored in sips, not given in gulps. (Adam Hartzell)

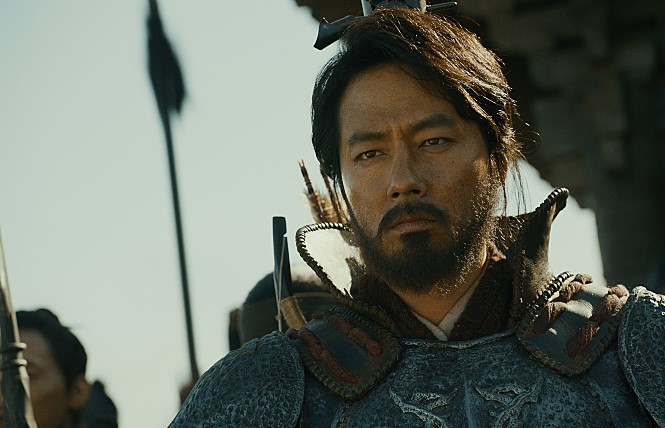

Hydraulic technician Choi Hyun-soo (Ryu Seung-ryong, The Piper), saddled with a gambling habit and estranged from his hard-working wife Eun-joo (Moon Jeong-hee, Cart), drives to a remote village called Seryeong. Having been appointed as the chief of the reservoir control station overlooking the village, he reluctantly takes up an offer to look into a new apartment in the middle of the night, but thick mist blowing out from the eerie lake hinders his view. Adding insult to injury, he is confronted by a road hog, an expensive SUV driven by the local landlord and dentist Oh Young-je (Jang Dong-gun, No Tears for the Dead). Young-je turns out to be a psychopathic sadist, routinely torturing his wife and young daughter Se-ryeong (Lee Re, How to Steal a Dog). On that night, he happened to be looking for the latter, who daringly escaped from her father's clutches during a whipping session. Tragically, Hyun-soo runs over Se-ryeong with his car. Distraught and frightened, he then makes the worst decision of his life, dumping her body into the lake and pretending nothing had happened. Seven years later, Hyun-soo is a death-row inmate, and his son Seo-won, now a young adult (Go Kyung-pyo, Horror Stories 2), is a professional diver, taken under the wing of a family friend and an ace underwater salvage man Seung-hwan (Song Sae-byuk, A Girl at My Door). Finally visiting his father soon to be executed, Seo-won gradually puts together the horrifying story of denial, vengeance and cruelty involving his father and Young-je.

Seven Years of Night is based on a best-selling mystery novel (2011) by Jeong Yoo-jeong, a former hospital nurse-turned-genre scribe, well-known for a series of hard-boiled thrillers vividly portraying psychopathic villains (most notably Origins of Species [2016], also soon to be adapted into a motion picture). The film adaptation, completed in 2016 but unable to secure a release date until 2018, is written and directed by Choo Chang-min, who had previously scored a critical and commercial hit with the Lee Byung-heon vehicle Masquerade (2012). He is clearly a competent director, expertly thrashing into shape the film's complicated flashback structure, and consistently sustaining the tone of moist dread and coiled anger. Some of his mises-en-scenes are very impressive, abetted by suitably creepy underwater photography of a submerged human habitat and fog-enshrouded green lighting of DP Ha Kyung-ho and LD Shin Tae-seob.

Seven Years of Night is based on a best-selling mystery novel (2011) by Jeong Yoo-jeong, a former hospital nurse-turned-genre scribe, well-known for a series of hard-boiled thrillers vividly portraying psychopathic villains (most notably Origins of Species [2016], also soon to be adapted into a motion picture). The film adaptation, completed in 2016 but unable to secure a release date until 2018, is written and directed by Choo Chang-min, who had previously scored a critical and commercial hit with the Lee Byung-heon vehicle Masquerade (2012). He is clearly a competent director, expertly thrashing into shape the film's complicated flashback structure, and consistently sustaining the tone of moist dread and coiled anger. Some of his mises-en-scenes are very impressive, abetted by suitably creepy underwater photography of a submerged human habitat and fog-enshrouded green lighting of DP Ha Kyung-ho and LD Shin Tae-seob.

As was the case with Masquerade, Choo works well with the actors, too, keeping Song Sae-byuk, an actor prone to scene-stealing show-off moments, subdued and in control, and letting the reliable Ryu Seung-ryong run the gamut of extreme emotions, from impotent rage to utter despair, but never allowing him to wade into the territory of self-indulgence or camp. One of the themes of Jeong's original novel is inheritance of (male) violence through intergenerational relationships (also dealt with in a much drier, more ironic manner in the short story "Anagura [An Eel-catcher]" by Suzuki Koji of the Ring fame), and as far as Choo remains focused on Hyun-soo's guilt-ridden consciousness, the film manages to convey this with reasonable clarity.

Unfortunately, Jang Dong-gun in the role of Young-je seriously undercuts this thematic thread. I feel bad about having to say this, since I am pretty sure Jang had only good intentions in landing this role, and objectively speaking, not much of what he does here is technically wrong or ruinously excessive. The problem is that once Jang is cast as the main villain, the screenplay begins to add all kinds of completely unnecessary excuses for his behavior. Jeong in her novel coolly examined the gears and pulleys of its villain's behavioral machinery, outwardly gentlemanly yet hideously manipulative. Jang conveys none of these truly evil qualities. Good-looking as ever in mid-forties (born in 1972), he seems stubbornly incapable of discarding his star persona, that of un bel homme who in the end must be coddled and understood by the (female) viewers. I think if he really took the idea of playing a sadistic bad guy seriously, Jang should have volunteered to get rid of all those scenes patently calculated to draw sympathy (including his big, slo-mo wailing upon the discovery of his daughter's body, one of the unintentionally embarrassing moments in otherwise an admirably taut thriller), or at least played them in such a way to highlight Young-je's socially manipulative, devious features. Again, I am sorry to have to make this unkind comparison, but Jeong Woo-sung's performance in Cold Eyes (2013), or even the crackpot Asura: City of Madness (2016), demonstrates what Jang is failing to do in this and his other recent films.

In fact, the overpowering presence of Jang Dong-gun as Young-je veers the entire movie away from critique of the patriarchy's poison (explored in the original novel) toward an acknowledgement, if not celebration, of patriarchal values. In the course of this turn-around, Seo-won loses his quasi-protagonist status, and Young-je's battered wife simply disappears from the movie version. In the end, Young-je degenerates into the kind of self-pitying macho bastard so familiar from countless Korean movies, the director's attempt to give him some kind of self-reflective interior life, perhaps a capacity for regret, entirely backfiring.

Seven Years of Night has all the right ingredients of a handsome-looking, effective Gothic melodrama, but it never gels into something genuinely moving or provocative. Although Jeong Yoo-jeong allegedly expressed approval over the way the movie had changed her characterizations, Choo's misguided attempt to bring a form of ethical "balance" to the relationship between Hyun-soo and Young-je has undermined some of the source novel's obvious strengths and muddled its emotional power.

Domestic box office records echoed the lukewarm reviews the film received, stalling at approximately 440 thousand tickets sold through the months of March and April 2018, not enough to earn back its rather high production cost. It will probably play somewhat better for the non-Korean viewers unfamiliar with the source novel, and, of course, for loyal international fans of Jang Dong-gun. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

A crude smartphone video shows two giggling high school students trespassing into what appears to be a rundown hospital corridor. They try to open the door numbered 402, and then the video abruptly terminates. The scene shifts, and Ha-joon (Wi Ha-joon, Coin Locker Girl), a YouTuber running a popular program entitled Horror Times who has just played smartphone video, vows to get to the bottom of the mystery surrounding Korea's most famous haunted mental asylum, Namyang Mental Hospital at Gonjiam. A team of eager volunteers is assembled: the Brave Girl Ji-hyun (Park Ji-hyun, The Chase), the camera expert Seong-hoon (Park Seong-hoon, A Frozen Flower), Seung-wook (Lee Seung-wook) the outwardly calm commentator for Horror Times, the Nice Girl Ah-yeon (Oh Ah-yeon), the scaredy-cat Je-yoon (Yoo Je-yoon), and the Glamour Girl Charlotte (Moon Ye-won). Equipped with state-of-the-art video gadgets that allow them to simultaneously film their own faces and the objects in front of them, they set up the camp near the decrepit, long-deserted Namyang Hospital building and wait until the clock hits midnight. Everything goes fine, as the members divvy themselves up to explore different floors, each with creepy facilities such as a shower room and a storage room inexplicably lined with coffin-like wooden boxes. The team, following the script written by Ha-joon with an ulterior motive to boost YouTube clicks and therefore his ad-based income, performs a séance calling for the ghosts, and it seems to work. However, some members begin to sense that something genuinely weird is going on, that has little to do with Ha-joon's script.

Gonjiam (I know, the title sounds as dorky in Korean as it does in English) is a modestly-budgeted found footage horror film. The primary PR hook for it has been that its setting, Namyang Mental Hospital, is a real place in Gonjiam County, Gwangju City, Gyeonggi Province, previously profiled by CNN as one of the seven creepiest deserted places in the world, along with Japan's Hashima the Battleship Island, Russia's Chernobyl and Mexico's Isla de las Muñecas. The ensuing publicity has clearly helped the film's box office performance (and reportedly stoked irritation of the owners of the estate, long suffering from thrill-seeking hooligans: the hospital site in real life is apparently ensconced right in the middle of a peaceful residential area and disappointingly mundane), as it sold robust 1.73 million tickets since its theatrical release in the second week of March, 2018, one of the best domestic performances for an out-and-out horror film in recent years.

Gonjiam (I know, the title sounds as dorky in Korean as it does in English) is a modestly-budgeted found footage horror film. The primary PR hook for it has been that its setting, Namyang Mental Hospital, is a real place in Gonjiam County, Gwangju City, Gyeonggi Province, previously profiled by CNN as one of the seven creepiest deserted places in the world, along with Japan's Hashima the Battleship Island, Russia's Chernobyl and Mexico's Isla de las Muñecas. The ensuing publicity has clearly helped the film's box office performance (and reportedly stoked irritation of the owners of the estate, long suffering from thrill-seeking hooligans: the hospital site in real life is apparently ensconced right in the middle of a peaceful residential area and disappointingly mundane), as it sold robust 1.73 million tickets since its theatrical release in the second week of March, 2018, one of the best domestic performances for an out-and-out horror film in recent years.

For a jaundiced fan of horror cinema like myself, it is difficult not to suppress a yawn as soon as "found footage" is mentioned, especially considering that Gonjiam's premise seems to be directly working off on The Blair Witch Project, the movie that started all the FF craze way back when. Yes, it is a low-budget horror film neither with anything profound to say about the universal human condition, nor particularly interested in developing nuanced characterizations or an involving narrative, but once you take this built-in limitation into account, the film declares itself a surprisingly decent nail-biter. It helps enormously that the writer and director behind the project is Jeong Beom-sik, who has proven his mojo with the now-classic Epitaph and the "The Escape" segment of Horror Stories 2, still one of the wackiest and weirdest pieces of Korean genre cinema I have seen in a long time. Jeong certainly knows how to juggle and keep afloat disparate and potentially confusing visual elements of the film, to keep the flow of sequences logical and legible and his young cast believable and sympathetic. Admittedly some ideas, such as an old graffiti spontaneously switching meaning from "Let's live" (salja) to "Suicide" (Jasal), likely a reference to the "Redrum" scene in The Shining, are borderline silly, but many of the scare effects, especially those focused on the spatial displacement suffered by the cast members, a la Mario Bava's Kill... Baby, Kill!, are genuinely effective. The sound design and almost imperceptible ambient music are also first-rate.

Intriguingly, Gonjiam, despite its streamlined structure and youth-oriented premise, shares a few thematic concerns with the more historically-minded Epitaph. There is a nod, in the form of an actual government newsreel footage, to the anti-Communist paranoia under the Park Chung Hee regime as one of the underlying causes of the hospital's "curse," and one of the movie's jolting set pieces duplicates the deservedly notorious, hideously scary "lullaby" scene from the 2007 film. The overarching theme of ghosts as the individuals temporally and spatially trapped in modern Korea's traumatic and unsavory past, trying to ensnare the innocent younger generation into their (zombie-fied) world-view, might be shared by the two films, and perhaps supplies an additional, subtle undercurrent of unease for the Korean viewers.

In the end not an earth-shaking work of art, Gonjiam nonetheless more than fulfills the modest expectations generated by its minimalist outlook, successfully showcasing Jeong's considerable prowess as a horror specialist. Based on the evidence displayed here, Netflix or Amazon should endow him with a five million-dollar-plus budget, so that his devious imagination could be fully indulged, without having to be constrained by the commercial calculations of the Korean theater-chain owners. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Gyeong-seok (O Man-seok, Our Town) is an up-and-coming aid-de-camp to a big-shot politician Yeom Jeong-gil (the TV drama veteran Kim Hak-cheol), but his real job is a safe-keeper for the latter's illegal stash of funds. Married to Yeom's harpy-like daughter and mystery writer (Come again? This is only one of the many weird and murky set-ups in the film) Ji-eun (Cho Eun-ji, A Bizarre Love Triangle), Gyeong-seok hightails to his wife's villa, where the money is hidden, with his lover Ji-young (Lee Eun-woo, a.k.a. Lee Na-ra, Moebius) and a bag of cash in tow. On the way to the tryst, the adulterous couple runs over a dog. When the dead mutt's self-proclaimed owner, Sun-tae (the singer-DJ Ji Hyun-woo, popular for the TV drama Awl), shows up, they feel guilty, annoyed, and suspicious in turn. It soon becomes clear that the perpetually grinning Sun-tae, who claims to be house-sitting for a neighboring unit, might be not only privy to Gyeong-seok's secret job, but also planning to bring some serious harm to him and his lover.

For the long stretches of its runtime, True Fiction plays like a soporific, overlong version of Won Shin-yeon's A Bloody Aria (2006), with grimy, foul-mouthed local yokels under the "leadership" of Sun-tae ganging up on Gyeong-seok. Writer-director Kim Jin-muk falls headfirst into one of the common traps for a debutant feature director, putting all his eggs in the one basket of keeping the narrative as convoluted and full of "surprises" as he possibly could, at the expense of other considerations such as building sympathetic and credible characters, proper management of tonalities, and legibility of action and motives. The result is a stuttering mixture of crushingly boring, utterly un-suspenseful, yet supposedly "tense" exchanges among the characters, on the one hand, and a series of increasingly frantic but emotionally uninvolving confrontations and back-stabbings on the other. All characters are so abjectly unsympathetic and hateful, to the point that, somewhere along the way, I began to root for Gyeong-seok, obviously meant to be the soulless villain of the piece, to just take out a golf club and beat the brain-springs out of Sun-tae and his "helpers" (something like this eventually does happen, alas, too late in my opinion).

For the long stretches of its runtime, True Fiction plays like a soporific, overlong version of Won Shin-yeon's A Bloody Aria (2006), with grimy, foul-mouthed local yokels under the "leadership" of Sun-tae ganging up on Gyeong-seok. Writer-director Kim Jin-muk falls headfirst into one of the common traps for a debutant feature director, putting all his eggs in the one basket of keeping the narrative as convoluted and full of "surprises" as he possibly could, at the expense of other considerations such as building sympathetic and credible characters, proper management of tonalities, and legibility of action and motives. The result is a stuttering mixture of crushingly boring, utterly un-suspenseful, yet supposedly "tense" exchanges among the characters, on the one hand, and a series of increasingly frantic but emotionally uninvolving confrontations and back-stabbings on the other. All characters are so abjectly unsympathetic and hateful, to the point that, somewhere along the way, I began to root for Gyeong-seok, obviously meant to be the soulless villain of the piece, to just take out a golf club and beat the brain-springs out of Sun-tae and his "helpers" (something like this eventually does happen, alas, too late in my opinion).

O Man-seok and Ji Hyun-woo are neither charismatic nor entertaining, but it is unlikely that they could have done much with their half-baked roles. Sun-tae is an especially confusing character: is he some kind of an avenging angel getting back at the Yeom family (What is his real connection to Ji-young anyway?), or just an unhinged psycho who cannot tell his imaginary "novel" apart from his real-life con game? This aspect is never clarified to the viewer's satisfaction, because Sun-tae is a total cipher: he might as well be a Smile icon plastered atop a bulky mountaineer's get-up.

Moreover, Kim seems to believe that he is bringing into the mix a genuine sense of irony (not a chance) as well as deeply felt political critique (his argument being that all politicians are evil and rotten to the core: right, what a jolting message for the South Koreans, so naïvely trusting of the pot-bellied hacks they regularly vote into power! Seriously, how could they live with something as corrupt as an electoral democracy?). It's all very macho-angry, predictable and dreary. The female characters in the film are divided into a cheesecake-flashing "love interest" subject to exploitation and dismissal, and a poodle-carrying hysterical b*tch. Neither Cho Eun-ji nor Lee Eun-woo deserves such clichéd (and frankly misogynistic) parts, after their rich and variegated careers.

Finally, to cap all this off, True Fiction features some of the most offensive dog-related vignettes I have seen in Korean cinema in recent years, one involving a sick joke about a pooch stew, and the other, even in worse taste, about a "man-bites-dog" situation (this assessment from me, a Korean guy who usually can't stand the Euro-American brouhaha about canine welfare in Asian societies). I venture to guess that these "jokes" will likely prevent the present motion picture from being added to the roster of Netflix New Releases anytime soon.

True Fiction is probably not the worst Korean film of 2018: for all I know, some local viewers might have found its hackneyed, twist-laden plot at least amusing, if not actually nail-biting (although its box office figures stand at the tepid 49 thousand tickets sold, outdistanced by even Pororo's Dinosaur Island Adventure). As for me, one or two more of these "politically relevant" pretzel-plot mystery thrillers from Korea, and I think I would need some type of vaccination. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Detective Jo Won-ho (Cho Jin-woong, Bluebeard) is an overworked narcotics detective obsessed with capturing the mysterious master criminal known only as Mr. Lee. The movie opens as Detective Jo's snitch, a teenage drug mule, is brutally murdered by Mr. Lee, and O Yeon-ok (Kim Sung-ryung, The Fatal Encounter), one of the latter's underlings, throws herself at the feet of Jo, when her colleagues are blown up sky high by a bomb. Miss O is convinced that Mr. Lee is getting rid of his management team to reboot his organization. Jo manages to find in the rubbles of the building a wounded young man, Seo Young-rak (Ryu Jun-yeol, Socialphobia), a low-ranking but important liaison officer for the syndicate. Persuading him that Mr. Lee needs to be punished for killing his surrogate mother, also an unintended victim of the blast, the detective enlists Young-rak's cooperation in interjecting himself into the deal between Jin Ha-rim (the late Kim Joo-hyuk, The Tooth and the Nail), the unstable Korean-Chinese supplier of raw materials for the merchandise, and Park Seon-chang (Park Hae-joon, Heart Blackened), the thuggish middle-rank boss. The Mission: Impossible-like ploy seems to work well, especially when an elusive faux-Christian minister Brian Lee (Cha Seung-won, Man on High Heels) comes out of the woodwork as the potential candidate for Mr. Lee's true identity. But Jo is yet not aware of the frightening extent to which the master criminal's spider-web of schemes has ensnared everyone around him.

Lee Hae-young, a high-profile screenwriter with many distinctive film projects under the belt, including Conduct Zero, Like a Virgin (which he also directed, one of Korea's first commercial films to feature a transgender protagonist) and 26 Years, had just helmed The Silenced, an interesting but not entirely convincing genre hybrid thriller set in the colonial period. He seemed like an odd choice for adapting Johnny To's lacerating Drug War (2013) into the Korean context. Indeed, given the latter's jaw-droppingly withering view of the Chinese law enforcement and social order, Asian masculinity, and the very notion of justice (all no doubt immaculately designed to stay legitimate within the boundaries set by the Chinese censorship), as well as its cuttingly precise filmmaking style that little resembles the contemporary Asian cinema and instead recalls a '70s William Friedkin or Paul Schrader, one might question if there was really any reason to remake it. It must have been obvious to everyone concerned, from the very beginning, that a literal, faithful replication would not have worked. As it turns out, Believer, while neither as powerful nor as ruthless as Drug War, has its own gaudy, genre-driven strengths. Sure, it is not an EBS documentary exposé of drug trade in South Korea, but, hey, it's no fault of your charcoal grill if you melt your rubber tire on it.

Lee Hae-young, a high-profile screenwriter with many distinctive film projects under the belt, including Conduct Zero, Like a Virgin (which he also directed, one of Korea's first commercial films to feature a transgender protagonist) and 26 Years, had just helmed The Silenced, an interesting but not entirely convincing genre hybrid thriller set in the colonial period. He seemed like an odd choice for adapting Johnny To's lacerating Drug War (2013) into the Korean context. Indeed, given the latter's jaw-droppingly withering view of the Chinese law enforcement and social order, Asian masculinity, and the very notion of justice (all no doubt immaculately designed to stay legitimate within the boundaries set by the Chinese censorship), as well as its cuttingly precise filmmaking style that little resembles the contemporary Asian cinema and instead recalls a '70s William Friedkin or Paul Schrader, one might question if there was really any reason to remake it. It must have been obvious to everyone concerned, from the very beginning, that a literal, faithful replication would not have worked. As it turns out, Believer, while neither as powerful nor as ruthless as Drug War, has its own gaudy, genre-driven strengths. Sure, it is not an EBS documentary exposé of drug trade in South Korea, but, hey, it's no fault of your charcoal grill if you melt your rubber tire on it.

Believer retains the tense and morally ambivalent relationship between the main investigating officer and the criminal-turned-reluctant-partner from Drug War, but its plot and characterization in the end significantly deviate from the Hong Kong actioner. Lee unfurls his plot almost languidly, spending little effort to mount suspense in the trendy, attention-deficit way, and instead heavily relies on the great cast to carry forward the aria-like set pieces toward the film's character-oriented resolution. For starters, Kim Joo-hyuk does a compelling job with what appears at the outset the most thankless and cliché-ridden role in the film, a drug lord hopelessly addicted to his own wares, making Jin at once contemptibly hilarious and rather unsettling, a thug whose speed-addled brain might at any moment snap to attention and see through Detective Jo's masquerade. Cha Seung-won rolls out his dialogue in the speech pattern of a TV evangelist crossed with a self-help guru, a Bill Murray doing impersonation of Deepak Chopra: he beautifully conveys narcissistic rottenness of Brian Lee, a snake-oil salesman who believes in his own con, with a serpentine tongue that spits venom. Among the colorful villains that populate the film, Cha's characterization comes closest to an outright political satire, but Director Lee thankfully does not push the point, like Kim Sung-soo did with a sledgehammer in Asura: City of Madness.

At the other end of the spectrum, Cho Jin-woong firmly anchors the film, whose Detective Jo goes through some unexpected, not exactly welcome realizations about himself: the character arc that I thought was handled quite well. If I were to push the American cinema analogy further, Cho at this point of his career reminds me a bit of Jeff Bridges, in the way that he makes the viewer note his robust physical presence in every role, yet does not necessarily rely on large "acting" to make his point. However, the movie ultimately belongs to Ryu Jun-yeol, who has perhaps the most difficult job in the whole shebang, keeping Young-rak's motivations and internal conflicts carefully under the wraps but not totally opaque to the viewers. Some have registered complaints that the young hoodlum makes little sense as a character, but I think Young-rak as portrayed in a clear-eyed, frosty manner by Ryu is a good foil for the film's more operatic villains. Playing greatly off one another, Cho and Ryu more or less make the film's risky climactic sequence work, which surely would have ruined the movie if tilted ever so slightly more toward a self-consciously melodramatic-confessional direction.

The film also deserves mention for containing some interesting supporting characters, one of the Lee Hae-young specialties, such as the deaf-mute brother-and-sister team of drug processors (Kim Dong-young and Lee Joo-young) who clearly treat Young-rak as more of a family member than a co-criminal, and Jo's female cop team member So-yeon (played by the very tall model Kang Seung-hyun), who is refreshingly not used as a comic relief and has the film's bloodiest fist- (and foot-) fight showdown with a gangster.

Believer is not really a slam-bang action film, although some of the set pieces, a few involving classic shoot-'em-ups between cops and gangsters, are pretty exciting and suitably violent. DP Kim Tae-gyung and Lighting Supervisor Hong Seung-cheol (Broken) as well as Production Designer Lee Ha-joon (Okja) and the art team do excellent work, the former keeping the palette just a touch excessive, without sliding into full-blown psychedelia, yet resolutely distinct from the blue-tinted art-gallery look of the usual, post-Michael Mann crime thrillers, and the latter pulling off some borderline-kitschy assignments such as setting up a state-of-the-art drug laboratory inside the Yongsan Station, of all places.

No doubt buoyed by its star power-- with most of its impressive cast in their full-throttle mode-- Believer scored 2018's first big domestic box office success, collecting 5.06 million tickets in approximately six weeks since its theatrical release in May 22, 2018. As I stated above, fans of Johnny To in his patented economical, precision-sniper mode might not see much to like here, but for me, the Korean not-quite-a-remake worked as a sort of cinematic graphic novel (this is not a put-down, just in case you are wondering), off-kilter and perhaps even borderline daft, but with some unexpected resonant character conflicts that pay off at the end. I am happy to check score one for Lee Hae-young, a talented screenwriter whose directorial effort had trouble escaping the alleged "minor" or "quirky" sensibility, whether such designation was fair or not, until now. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

The Korean Peninsula, 2029 C.E.: The North and South Korean governments have set up a five-year plan for reunification, against objections of surrounding nations, plunging the South Korean society into an economic and political chaos. Im Joong-kyung (Kang Dong-won, Vanishing Time), a member of the elite Special Weapons Unit created within the police force, mired in controversy due to their accidental massacre of female high school students. Traumatized by the experience, Im hesitates before dispatching a teenage courier working for the armed rebel group known as the Sect. The girl commits suicide by triggering a bomb, but Im is given a memento of the dead girl by his Metropolitan Police Security Division friend Han Sang-woo (Kim Mu-yeol, Forgotten), to be delivered to the girl's sister Lee Yoon-hee (Han Hyo-joo, Cold Eyes). However, this was a ploy to set Im up as a fall guy. He and Lee become embroiled in a political struggle among the Special Weapons Unit, spearheaded by the battle-scarred Jang Jin-tae (Jung Woo-sung, Asura: The City of Madness), the Security Police and the Sect, all of whom are ready to resort to back-stabbing deceptions and cold-blooded murders to get what they want.

Financed by Warner Brothers Korea with a large budget (around twenty million dollars), Illang: The Wolf Brigade, adapted from the Japanese animation auteur Oshii Mamoru's multimedia "Kerberos Panzer Cop" series, especially the animated prequel Jin-roh: The Wolf Brigade (2009, directed by Okiura Hiroyuki based on Oshii's screenplay), has been one of the most highly anticipated Korean films of the year. The designated helmer, Kim Jee-woon (The Age of Shadows), is well known for his deep love for Japanese animation, and his eye for visual splendor and propensity for elaborate set pieces were considered strong assets in transporting the unique texture of the high-end Japanese animation into live-action cinema, the task at which Japanese filmmakers have not excelled over the years, to say the least. For every serviceable adaptation like Miike Takashi's Yatterman or Anno Hideaki's Cutey Honey, there are half a dozen unmitigated disasters like Gatchman, Devilman and Iron Giant No. 28, so it is not surprising that Oshii and his production company were willing to place a bet on an internationally recognized Korean cineaste.

Financed by Warner Brothers Korea with a large budget (around twenty million dollars), Illang: The Wolf Brigade, adapted from the Japanese animation auteur Oshii Mamoru's multimedia "Kerberos Panzer Cop" series, especially the animated prequel Jin-roh: The Wolf Brigade (2009, directed by Okiura Hiroyuki based on Oshii's screenplay), has been one of the most highly anticipated Korean films of the year. The designated helmer, Kim Jee-woon (The Age of Shadows), is well known for his deep love for Japanese animation, and his eye for visual splendor and propensity for elaborate set pieces were considered strong assets in transporting the unique texture of the high-end Japanese animation into live-action cinema, the task at which Japanese filmmakers have not excelled over the years, to say the least. For every serviceable adaptation like Miike Takashi's Yatterman or Anno Hideaki's Cutey Honey, there are half a dozen unmitigated disasters like Gatchman, Devilman and Iron Giant No. 28, so it is not surprising that Oshii and his production company were willing to place a bet on an internationally recognized Korean cineaste.

On the other hand, there were legitimate concerns about whether Oshii's highly idiosyncratic, intellectually sophisticated, some might call pretentious, approach to the medium of anime could be turned into the kind of crowd-pleasing summer blockbuster that Warners Korea was obviously hoping for. Jin-roh is well known for its deep-dish critique of the complacency of postwar Japanese democracy (Oshii set his manga/animation/live-action film series in an alternative universe in which Japan had been a part of Allied Powers and became occupied by the victorious Nazi Germany instead of the U.S. after 1945) as well as its notoriously downbeat resolution, its message being dehumanization of a decent person in a militarized society constantly beset by baroque political struggles. To make things worse, the Hollywood remake of Oshii's magnum opus, Ghost in the Shell (2017), did not exactly inspire confidence in the Illang project. The U.S. version jettisons the entire philosophical contents of the original animation film and replaces it with a turgid, "humanistic" storyline that could be read as a bizarre quasi-apologia for corporate whitewashing of the Japanese animation in the form of casting Scarlett Johansson in the lead.