2005

From left: "The President's Last Bang", "Tale of Cinema", "Welcome to Dongmakgol", "A Bittersweet Life"

The year 2005 turned out to be somewhat of a rejuvenation after the comparatively weak offerings of 2004. Although Korean films did not win any major awards from top-ranked festivals in 2005, as they had the previous year, the films themselves provided a much broader range of quality. From large commercial releases to low-budget digital films, from action films to romantic comedies, there was more or less something for everyone in 2005, and audiences responded with strong interest and support.

Commercially, the first half of the year showed an unmistakable drop from the previous year, but a string of major box office hits followed in the second half, including Welcome to Dongmakgol, Sympathy for Lady Vengeance, Marrying the Mafia 2, You Are My Sunshine, Typhoon, and in the closing days of the year, King and the Clown. Critics seemed happy as well, with films such as Hong Sangsoo's Tale of Cinema, Im Sang-soo's The President's Last Bang, and Lee Yoon-ki's This Charming Girl providing much to talk about in addition to the above.

Some government support helped to ensure that small films got released, too. A total of 17 films with budgets of less than $1 million were released in 2005, compared to only 3 in 2004. Many of these releases were only on a single screen, and attendance tended to be light, however for many micro-budget films even a single screen can make a difference. Among critics, Yoon Jong-bin's The Unforgiven received the most notice among these smaller releases, although films such as Git, Spying Cam and Geochilmaru: The Showdown had their supporters.

Most of the big news in 2005 was taking place outside of Korea, however. A wave of popularity enjoyed by Korean entertainers throughout Asia, particularly in Japan, reached new levels of intensity. Korean films such as Windstruck, April Snow and then A Moment to Remember set box office records in Japan. Meanwhile Korean TV dramas such as Jewel in the Palace enjoyed astounding levels of success in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China. Japanese film companies paid a total of $76 million for rights to Korean films in 2005, which by itself would be enough to completely fund 28 average-sized films. The infusion of money into the film industry caused a shift in power relations, and set off some ugly public spats between producers and star management companies.

If there was bad news in 2005, it was the dawning realization that the DVD market in Korea would never emerge into a normal, healthy industry. Young Koreans show a clear preference for downloading movies off the internet -- 80% of high school students are said to have tried it -- and in the absence of any viable legal sites, illegal providers of pirated movies flourished. At the same time, however, Koreans got a glimpse of the future, with the debut of satellite and terrestrial broadcasting for mobile phones, and the promise of various new, hi-tech means of watching films set to emerge in the next few years.

Reviewed below: Git (Jan 14) -- Marathon (Jan 27) -- The President's Last Bang (Feb 3) -- This Charming Girl (Mar 10) -- Crying Fist (Apr 1) -- A Bittersweet Life (Apr 1) -- Blood Rain (May 4) -- The Bow (May 12) -- Antarctic Journal (May 19) -- Tale of Cinema (May 26) -- The Aggressives (June 2) -- Rules of Dating (June 10) -- Green Chair (June 10) -- The Red Shoes (June 30) -- Voice (July 15) -- Mokdugi Video (July 15) -- Sympathy for Lady Vengeance (July 29) -- Welcome to Dongmakgol (Aug 4) -- Murder, Take One (Aug 11) -- The Wig (Aug 11) -- Cello (Aug 18) -- April Snow (Sep 8) -- Duelist (Sep 8) -- Geochilmaru: The Showdown (Sep 15) -- Camellia Project (Sep 16) -- You Are My Sunshine (Sep 23) -- Sa-Kwa (n/a) -- All For Love (Oct 7) -- Princess Aurora (Oct 27) -- Love Talk (Nov 11) -- The Unforgiven (Nov 18) -- Wedding Campaign (Nov 23) -- When Romance Meets Destiny (Nov 23) -- Five Is Too Many (Nov 25) -- Bystanders (Dec 1) -- Love is a Crazy Thing (Dec 9) -- Typhoon (Dec 14) -- Blue Swallow (Dec 29) -- King and the Clown (Dec 29).

| Korean Films | Nationwide | Seoul | Release | Weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | King and the Clown | 12,302,831* | 3,667,849* | Dec 29 | 7 |

| 2 | Welcome to Dongmakgol | 8,008,622 | 2,435,088 | Aug 4 | 11 |

| 3 | Marrying the Mafia 2 | 5,635,266 | 1,451,468 | Sep 8 | 7 |

| 4 | Marathon | 5,148,022 | 1,552,548 | Jan 27 | 9 |

| 5 | Typhoon | 4,094,395* | 1,229,971* | Dec 14 | 6 |

| 6 | Another Public Enemy | 3,911,356 | 1,167,828 | Jan 27 | 6 |

| 7 | Sympathy for Lady Vengeance | 3,648,808 | 1,375,194 | Jul 29 | 5 |

| 8 | Mapado | 3,090,467 | 922,647 | Mar 10 | 8 |

| 9 | You Are My Sunshine | 3,051,134 | 1,063,480 | Sep 23 | 6 |

| 10 | All For Love | 2,533,103 | 902,189 | Oct 7 | 5 |

| All Films | Nationwide | Seoul | Release | Weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | King and the Clown (Korea) | 12,302,831* | 3,667,849* | Dec 29 | 7 |

| 2 | Welcome to Dongmakgol (Korea) | 8,008,622 | 2,435,088 | Aug 4 | 11 |

| 3 | Marrying the Mafia 2 (Korea) | 5,635,266 | 1,451,468 | Sep 8 | 7 |

| 4 | Marathon (Korea) | 5,148,022 | 1,552,548 | Jan 27 | 9 |

| 5 | King Kong (US-NZ) | 4,232,430* | 1,352,121* | Dec 15 | 7 |

| 6 | Typhoon (Korea) | 4,094,395* | 1,229,971* | Dec 14 | 6 |

| 7 | Another Public Enemy (Korea) | 3,911,356 | 1,167,828 | Jan 27 | 6 |

| 8 | Sympathy for Lady Vengeance (Korea) | 3,648,808 | 1,375,194 | Jul 29 | 5 |

| 9 | Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (US) | 3,615,300* | 1,239,817* | Dec 1 | 6 |

| 10 | Mr. and Mrs. Smith (US) | 3,546,900 | 1,206,120 | Jun 16 | 7 |

* Includes tickets sold in 2006. Source: nKino, Korean Film Council (KOFIC).

Seoul population: 10.32 million

Nationwide population: 48.8 million

Market share: Korean 58.7%, Imports 41.3% (nationwide)

Films released: Korean 83, Imported 213

Total admissions: 145.5 million (=$873 million)

Number of screens: 1,648 (end of 2005)

Exchange rate (2005): 1028 won/US dollar

Average ticket price: 6172 won (=US$6.00)

Exports to other countries: US$75,994,580 (Japan: 79%)

Average budget: 4.0bn won including 1.3bn p&a spend

Short Reviews

These are some reviews of the features released in 2005 that have generated the most discussion and interest among film critics and/or the general public. They are listed in the order of their release.

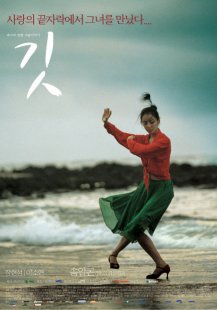

![]() Git (a.k.a. Feathers in the Wind)

Git (a.k.a. Feathers in the Wind)

Sometimes small-scale, informal projects can liberate a director. Without the pressure and weighty expectations involved in producing a major work, inspiration flows freely and the result is an even more accomplished piece of art. This may have been what happened with Git by Song Il-gon, the director of Flower Island (2001), Spider Forest (2004), and various award-winning short films including The Picnic (1999).

Git was originally commissioned as a 30-minute segment of the digital omnibus film 1.3.6. Comprising works by Jang Jin (Someone Special), Lee Young-jae (Harmonium in My Memory) and Song, 1.3.6 was intended to explore environmental themes and was slotted to open the first Green Film Festival in Seoul in late October. Alas, the festival's expectations were confounded, first in that only Lee Young-jae's work really engaged environmental issues in a direct way (the other two were merely set in rural areas), and second by the fact that Song went out and shot a 70-minute film. As an omnibus work, 1.3.6 has to be considered a failure, especially as the three films (Jang's amusing Sonagi Epilogue, Lee's poorly-received Mobius Strip, and Song's poetic Git) don't match, not just in length but in form, content, mood, style, and quality.

But if Song betrayed the spirit of the omnibus project, he remained true to the needs of his film. Git centers around a film director who, in the middle of starting his next screenplay, remembers a promise he'd made ten years earlier. While staying on a remote southern island off Jeju-do, he and his girlfriend of the time agreed to come back and meet at the same motel exactly ten years in the future. Now, years after breaking up, he returns to the small island named Biyang-do, wondering if his ex-girlfriend will remember their appointment. (It seems appropriate that Git's basic setup recalls Richard Linklater's Before Sunset, another film that stands out for the beauty and simplicity of its construction)

But if Song betrayed the spirit of the omnibus project, he remained true to the needs of his film. Git centers around a film director who, in the middle of starting his next screenplay, remembers a promise he'd made ten years earlier. While staying on a remote southern island off Jeju-do, he and his girlfriend of the time agreed to come back and meet at the same motel exactly ten years in the future. Now, years after breaking up, he returns to the small island named Biyang-do, wondering if his ex-girlfriend will remember their appointment. (It seems appropriate that Git's basic setup recalls Richard Linklater's Before Sunset, another film that stands out for the beauty and simplicity of its construction)

On Biyang-do, the director -- named Jang Hyun-seong, the same as the actor who portrays him -- is overpowered with both memories of the past and the beauty of the island. As he waits, the pressures of his work life start to recede, and he becomes acquainted with the young woman who runs the motel. Named Lee So-yeon (played by -- sure enough -- actress Lee So-yeon of Untold Scandal), the woman is twelve years his junior, and possesses an unusual energy and enthusiasm.

Although the general path followed by the plot is pretty straightforward, Song leads us down many odd and fascinating detours. There is So-yeon's uncle, a middle-aged man with bleached blonde hair who hasn't spoken since his wife abandoned him. A peacock appears on the island, with no clear explanation or motivation. And the tango, a very un-Korean pasttime, makes a striking appearance in the film. In Song's other works, such elements sometimes feel forced or self-consciously arty, but here they blend with the otherworldly presence of the island and add a sense of mystery.

Git (which means either a triangular flag or "feather" in Korean) is surprising in several respects. One is that such a low-budget film looks so good visually. In Flower Island, Song showed an unusual talent for the aesthetics of digital cinema, but here he takes it one step further. To capture a natural setting so well on a medium that often feels cold and sterile is an unusual accomplishment.

The relaxed, convincing performances of the actors also deserve notice. Lee So-yeon makes her slightly thin character memorable through considerable screen presence, while Jang Hyun-seong of independent films Nabi and Rewind gives the performance of his career. Whatever we feel about the character he portrays, Jang's performance is so real and natural that we can't help but be drawn to him.

In a year that has been lacking in unexpected discoveries, Git is an exciting find. At its rousing premiere at the Green Film Festival in Seoul, a prominent Korean film critic told me it may be the best romance Korea has ever produced. One hopes that it will be liberated from the other two segments of 1.3.6. and distributed on its own. At 70 minutes, it is a perfectly respectable length for a stand-alone feature film, and this is a movie that deserves to travel. (Darcy Paquet)

There was a lot going on in the world of Korean film at the beginning of 2005. The controversy of The President's Last Bang was being played out in the courtrooms and in the entertainment news. The collapse of the PiFan Film Festival was a hot topic and the hype surrounding the impending release of Another Public Enemy was overwhelming. Almost missed among all that was a quiet film directed by a virtual unknown but starring the talented Jo Seung-woo. The media found it interesting as 'a story of human triumph' but most people seemed certain that Kang Woo-suk's feature would dominate the box office. That all changed however, after Marathon had its press screening.

It was reported immediately after in numerous newspapers that the journalists in attendance applauded long and hard following the press screening and that most of them were in tears. The question and answer session with the director and lead actors that was held after the showing went on for much longer than anyone was accustomed to. Most questions had to do with how Jo Seung-woo was able to convincingly take on the role of an autistic young man.

It was reported immediately after in numerous newspapers that the journalists in attendance applauded long and hard following the press screening and that most of them were in tears. The question and answer session with the director and lead actors that was held after the showing went on for much longer than anyone was accustomed to. Most questions had to do with how Jo Seung-woo was able to convincingly take on the role of an autistic young man.

What followed next was a powerful nine-week run in the domestic box office where the film eventually went on to gather more than 5 million viewers. Although it did open in the number two seat slightly behind Another Public Enemy, word of mouth soon launched it into the number one position during its second week. More and more newspapers began to compare its success with that of another sleeper hit, The Way Home, but Marathon soon out-performed that movie as well.

Much of the credit for the success of Marathon falls squarely on the shoulders of Jo Seung-woo. His performance is worthy of the considerable praise that has been heaped on it. Jo convincingly becomes Cho-won, a young man born with autism. In his younger days, Cho-won was prone to tantrums and violence against himself, but the special school his mother enrolled him in and the different athletic activities she taught him eventually helped Cho-won to cope with the world around him. After he takes third place in a 10km marathon, his mother sets her goals for her son to run a full 40-km marathon in under four hours. However, it is uncertain whether or not Cho-won shares her dreams or if he is just doing what he is told because, as his brother puts it, he is incapable of rebelling against his mother.

Kim Mi-sook does an outstanding job as a mother spurred on to never give up on her son, through a mixture of fiercely defensive love and an enormous amount of guilt. She skillfully brings Cho-won's mother, Kyeong-sook, to life as a flawed protector of her son. Her obsession to make up for her past failings with Cho-won lead her to virtually ignore the needs of the rest of her family, which succeeds in driving them away emotionally and physically. When asked by a swimming instructor if she has any wish for herself, she replies that she wishes to die a day after Cho-won. Kyeong-suk believes if that were to happen, she would be able to take care of her son for his entire life, but her motives for saying that are later thrown back in her face, and she is accused of needing Cho-won to stay with her more than her son needs her.

Mentioned at the end of the movie is the fact that the characters of Cho-won and his mother are based on real people. Cho-won was inspired by Bae Hyeong-jin. Just 22-years old at the time of this film's release, Hyeong-jin had already participated in several marathons and a triathlon. He has since gone on to become somewhat of a celebrity, appearing on talk shows and even having a line of TV commercials with SK Telecom. Described as 'having a mind of a five-year old', Mr. Bae is an accomplished athlete and many of the events of his childhood are depicted accurately on screen. His mother involved him in many physical activities which he seemed to enjoy as a form of therapy, and had him keep a journal. It is from here that the misspelled Korean title of the movie originated. ("Mar-a-ton" should be spelled "Ma-ra-ton" -- similarly, the official way to write the film's English title is with a backwards "R")

Director Jeong Yun-cheol spent two years interviewing Bae and documenting the lives of him and his family. While he had directed a couple of short films prior to Marathon, the last being in 1999, Jeong had more recently worked as an editor for the film Three and as an art director for Wonderful Days. After this emotionally-charged runaway hit, it seems likely that we will be seeing more from him in the near future. (Tom Giammarco)

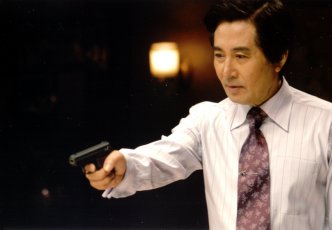

Some have referred to Im Sang-soo's The President's Last Bang as "the most political film in Korean history." Certainly, few works have stirred up the same level of heated public debate as this portrayal of the night when Park Chung-hee -- an authoritarian president who took power in a 1961 military coup and held it until 1979 -- was shot and killed by his chief of intelligence. Although Korea has changed beyond recognition in the 25 years since Kim Jae-gyu pulled the trigger, Park's legacy remains an unresolved question for much of the Korean populace. Complicating the matter, Park's daughter now leads Korea's centre-right opposition party, ensuring that the historically themed Last Bang would be read as a comment on the present as well as the past.

The film itself has got somewhat lost in the controversy surrounding its release, at which time a judge from the Seoul Central Court ordered that four minutes of documentary footage be removed, since it might "confuse" viewers as to what is fact and what is fiction. The footage -- clips of anti-government protests shown at the film's opening, and images from Park's funeral that accompany the end credits -- were important to the overall work, and the four minutes of black screen which appear in their place leave the audience with an altogether different viewing experience.

Many have viewed Last Bang as a bit of character assassination aimed at the late President Park. An observant reader on the Koreanfilm.org discussion board noted that this was more or less equivalent to making a movie about George Bush snorting cocaine and driving drunk in his youth. The most offensive bits may actually sneak past the radar of many foreign viewers: the tendency of Park and his advisors to speak in Japanese, his portrayed fondness for Japanese enka songs, his habit of holding late night drinking parties with young girls, and his cowardice in the face of danger (well, the latter two are easy to catch). Just why Park's fondness for things Japanese should be so controversial requires a short history lesson, but suffice it to say that he is being portrayed as being associated and aligned with Korea's former colonizers.

Many have viewed Last Bang as a bit of character assassination aimed at the late President Park. An observant reader on the Koreanfilm.org discussion board noted that this was more or less equivalent to making a movie about George Bush snorting cocaine and driving drunk in his youth. The most offensive bits may actually sneak past the radar of many foreign viewers: the tendency of Park and his advisors to speak in Japanese, his portrayed fondness for Japanese enka songs, his habit of holding late night drinking parties with young girls, and his cowardice in the face of danger (well, the latter two are easy to catch). Just why Park's fondness for things Japanese should be so controversial requires a short history lesson, but suffice it to say that he is being portrayed as being associated and aligned with Korea's former colonizers.

Personally, I love the George Bush analogy and I agree that director Im was out to settle a few scores with the many admirers of the former president. However I can't accept that this is the film's key purpose. If that were the case, there would be no reason to structure the film in the unusual way it is put together. Namely, the emotional climax -- Kim blowing Park's brains out -- occurs not at the end, but halfway through the film. As much of the plot is devoted to what happens after the event, as to what comes before.

Few filmmakers adopt such a strategy, though Atom Egoyan's The Sweet Hereafter (1997) comes to mind as another example of a film with its emotional climax in the middle, rather than the end. The unusual structure has opened Last Bang up to criticism, with many maintaining that the work loses its energy or focus in the second half. The result for me, however, is to make it much more of a thinking film than an emotional film. And I maintain that there is enough going on here to justify it as an object of study. (I should also note here in fairness to the director that the documentary footage that is meant to be screened over the end credits does pack a complex emotional punch. Without it, the film's ending is emotionally monotone.)

I read Last Bang as a film about history. Of course, it covers a specific historical incident, and also tries to capture the mindset of an authoritarian nation (the press kit calls it a film about "when a military society turns the gun on itself"). But most of all, this is a film about a small group of individuals who consciously decide to change history. To what extent can an individual, or a small group of people, really do that? This is what I think the movie is asking.

The process of unleashing change is portrayed as being unexpectedly simple. Im Sang-soo brings the events of this famous night down to a very human level, through evocative details concerning the many personalities involved, and through his liberal use of black humor (a perfect antidote to the chest-thumping heroism we see in other Korean films based on history). Thus, the final act that brings down the Park era comes across as being quite matter-of-fact.

Yet in the chaos that follows the shooting, we gradually realize that Kim Jae-gyu's ambition to transform Korean history is up against forces more powerful than the slain dictator. An individual can set loose the forces of history, but cannot control them. Those who are familiar with Korean history will know that Park may have made his exit on that night, but the oppressive military dictatorship lived on in another form.

In this sense the character of Kim Jae-gyu, portrayed masterfully by Baek Yoon-shik (Save the Green Planet), may be Im Sang-soo's greatest creation. Every sentence uttered by Baek resonates beyond its immediate context, and his actions embody a prototype that reappears in many guises throughout history. True, the entire ensemble cast is nothing short of fantastic, including a career-reviving performance by Han Suk-kyu, but everything in the film boils down to Baek's character.

Three cheers to Im Sang-soo. In making this leap from sex (a preoccupation of his previous films Girls Night Out, Tears and A Good Lawyer's Wife) to politics -- perhaps not such a long leap after all? -- he has given Korean cinema a much-needed shot in the arm. Now, the only work remaining is to get this film back from its censors. Unlike decisions made by the ratings board, the court's ruling applies internationally as well as in Korea, so it is illegal to screen the uncut version of the film anywhere in the world. Godspeed to the appeals process. (Darcy Paquet)

Jeong-hye (Kim Ji-soo) is a twenty-something single woman working at a post office. She lives alone in a cheap-looking apartment building, politely answering her aunt's irritating phone calls, purchasing meals, even packets of kimchi, through mail-order service, and taking care of plants. Jeong-hye is neither autistic nor misanthropic: she enjoys drinking beer and chatting with her co-workers, for one. It is only that she is perfectly happy with remaining in the background of the hustle-bustle of Korean city life. Nonetheless, Jeong-hye's life is beginning to show signs of change. She adopts a lovely kitten. She invites an equally shy and very absent-minded writer (Hwang Jeong-min, A Bittersweet Life, A Good Lawyer's Wife) to a dinner at her place. Finally, a chance encounter with a troubled young man (Seo Dong-won) leads her toward an attempt to address a long-repressed trauma.

Winner of the Best Film Prize at the 2004 Pusan Film Festival's New Currents Section, This Charming Girl is a quietly effective character study, made in cinema verite style but nearly completely devoid of the kind of pretensions and self-importance that plague many first-time features. Director Lee Yoon-ki shows a commendable discipline in keeping his hands largely invisible. It is no mean feat to capture the characters in intimate, unguarded moments with handheld camera but to keep the stance non-intrusive, which is what Lee accomplishes here. When the film slides from objective reality into Jeong-hye's subjective vision (limited to the daydream visitations of her mother, played by veteran actress Kim Hye-ok [Green Chair, Our Twisted Hero]), the transition is so natural that we do not even question whether she is experiencing a flashback, visualizing a wish, or seeing a ghost.

Winner of the Best Film Prize at the 2004 Pusan Film Festival's New Currents Section, This Charming Girl is a quietly effective character study, made in cinema verite style but nearly completely devoid of the kind of pretensions and self-importance that plague many first-time features. Director Lee Yoon-ki shows a commendable discipline in keeping his hands largely invisible. It is no mean feat to capture the characters in intimate, unguarded moments with handheld camera but to keep the stance non-intrusive, which is what Lee accomplishes here. When the film slides from objective reality into Jeong-hye's subjective vision (limited to the daydream visitations of her mother, played by veteran actress Kim Hye-ok [Green Chair, Our Twisted Hero]), the transition is so natural that we do not even question whether she is experiencing a flashback, visualizing a wish, or seeing a ghost.

Much of the film's strength must be attributed to the brilliant casting of Kim Ji-soo in the role of Jeong-hye. When I first saw the film, I pegged Kim to be a newcomer with only a theatrical background: in other words, I assumed that her utter lack of affectation in front of the lens was due to her (fortuitous) lack of familiarity with the moviemaking process. I was therefore stunned to find out later that Kim was a well-known figure in TV drama, most recently featured in MBC's The Age of Heroes (2004), with more than ten years of experience in front of the camera. Not only does she not break the rhythm of her performance against extreme long takes and close ups, that reveal minute abrasions and scars in her face, she also makes Jeong-hye absolutely believable in her hesitation and withdrawal, without making her neurotic or eccentric. It is an eye-opening performance the likes of which has seldom been seen in Korean cinema, especially melodramas that often push the actor's emotive capacity to maximum overdrive.

Part of the film's attraction comes from the thrill of anticipating when Jeong-hye will break from her routine and reveal her inner turmoil. When it does happen, the "revelation" is inevitably disappointing in its predictability. The plot development leading to Jeong-hye's confrontation with the source of her trauma is one of the film's few obvious weaknesses, even though the sequence in question features another terrific performance by Lee Dae-yeon (Camel(s), the psychiatrist in A Tale of Two Sisters) and a breathtaking long take inside a lady's restroom, showcasing Kim's tour de force performance.

We live in a world where cinema verite takes of sweaty, gymnastic sex or of characters languorously inhaling cigarettes with vacant eyes automatically cue us that they are meant to be serious "art" films. This Charming Girl, on the other hand, is like an entire film devoted to one of the "extra" figures appearing for a minute or so in these movies, say, a post-office clerk who processes the protagonist's Sturm und Drang letter to her divorced husband, and immediately exits the movie. Director Lee Yoon-ki and the filmmakers, adapting Woo Ae-ryung's novel, deliberately focus on such a seemingly boring and inconsequential character, and restore her integrity as a personage: she is revealed to have an inner world just as mysterious and absorbing as those of the conventional "art" film characters. In the end, it is the film's unwavering gaze, close and proximate, yet deeply compassionate and respectful, that renders This Charming Girl so powerful, and, in collaboration with Kim Ji-soo's superb portrayal, makes Jeong-hye one of the most fascinating characters in recent Korean cinema. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

When director Ryoo Seung-wan made his debut in 2000 with the independent feature Die Bad, Korean critics could hardly contain their enthusiasm. Here, they said, was a uniquely talented director with a hard-edged, innovative style who could breathe new life into the aesthetics of independent-minded cinema. Few people listened to Ryoo's protests that he was, at heart, a genre filmmaker. He pointed to his goofy internet short Dazimawa Lee as much more in keeping with his innate style. Sure enough, his next two features, No Blood No Tears (2002) and Arahan (2004) were more obviously structured around genre cinema, though he dissected and blended genre archetypes in fascinating ways. Critics, their expectations confounded, were unimpressed, particularly with Arahan. When will you stop fooling around and make something serious, they seemed to be asking.

Though not really a submission to the critics' wishes, the gritty and at times shocking Crying Fist represents a synthesis of the harsh realism Ryoo displayed in Die Bad and the commercial elements of his later work. Much of the film concentrates on the day-to-day experiences of two unrelated men, and contains almost nothing in the way of genre elements. The movie's resolution then plays out along the lines of the boxing film, but with one key difference that turns the genre completely on its head.

Though not really a submission to the critics' wishes, the gritty and at times shocking Crying Fist represents a synthesis of the harsh realism Ryoo displayed in Die Bad and the commercial elements of his later work. Much of the film concentrates on the day-to-day experiences of two unrelated men, and contains almost nothing in the way of genre elements. The movie's resolution then plays out along the lines of the boxing film, but with one key difference that turns the genre completely on its head.

Kang Tae-shik (Choi Min-shik) is a former Asian Games silver medallist whose life is at a dead end. His past glory worth almost nothing in the present day, he has found a creative but strenuous way to earn money: he becomes a human punching bag. In the meantime, his disintegrating marriage places great strain on both wife and husband, not to mention their young son.

Yu Sang-hwan (Ryoo Seung-beom) is a delinquent from a crumbling neighborhood who gets by on committing petty theft and harassing students. His relationship with his father, younger brother and grandmother is tenuous at best. One day his life is turned upside down, and like Tae-shik, he reaches the nadir of his existence. More out of frustration than anything else, he takes up boxing.

In Korea this film has drawn interest for pairing an acclaimed veteran actor with perhaps the most talented of the younger generation stars. All the more interesting, then, that Ryoo Seung-beom, the director's younger brother, should end up outshining the lead from Oldboy. Ryoo's portrayal of Sang-hwan (which incidentally is the same name of the characters he played in Arahan and Die Bad) is a perfect embodiment of caged fury. He speaks very little, but his body language radiates deep-seated anger and pain. Put simply, Ryoo's performance is mesmerizing, and watching him is one of the film's biggest pleasures. (Those who saw him in Arahan will find him completely unrecognizable.) Meanwhile Choi Min-shik also gives an excellent performance, but since he portays a character whose spirit has essentially been snuffed out, it's harder to relate to him. We get a strong sense of the aimlessness and desperation he feels, but this also makes the middle sections of the film somewhat tiring to watch.

The viewer's patience is rewarded by the end, however, in a resolution that is emotionally moving on the level of Failan, and backhandedly subversive in its construction. Think of virtually any boxing movie, and you envision a likeable central character (underdog) fighting at high stakes against a formidable opponent. As viewers, our emotional energy is funneled into the main character, almost to the point where we're the ones throwing the punches. Unspoken nationalistic or prejudicial feelings sometimes creep unawares into our minds. "Kill that German whore!" we scream while watching Million Dollar Baby.

Now imagine a boxing movie where two men who desperately need a break in life, who we both empathize with so much that it hurts, step into the ring against each other. Who do we cheer for? It's such a simple variation on the standard formula, but it causes the whole generic structure of viewer loyalties and triumph-against-odds expectations to crash down like a house of cards. Watching this film's gripping resolution play out, we have no idea what will happen, and we hardly even know what to wish for. (Darcy Paquet)

A Bittersweet Life opens with a gorgeous black and white image of a willow tree tossing in the breeze. As color slowly starts to bleed into the frame, we hear a voiceover by the main character Sun-woo: "On a clear spring day, a disciple looked at some branches blowing in the wind, and asked, 'Master, is it the branches that are moving, or the wind?' Without even looking to where his pupil was pointing, the teacher smiled and said, 'That which moves is neither the branches nor the wind, it is your heart and mind.'"

Sun-woo (Lee Byung-heon) is a man whose heart and mind remain closed to wind, rain, or disruptive emotions. For the past seven years he has served his gangster boss with unflinching exactitude. He manages an upscale bar called La Dolce Vita (which echoes the film's original Korean title), and he despatches people who get in the boss's way with skill and efficiency. The boss (Kim Young-cheol) trusts him so much that he asks Sun-woo to look after his mistress (Shin Min-ah), and to kill her if she is being unfaithful.

Sun-woo (Lee Byung-heon) is a man whose heart and mind remain closed to wind, rain, or disruptive emotions. For the past seven years he has served his gangster boss with unflinching exactitude. He manages an upscale bar called La Dolce Vita (which echoes the film's original Korean title), and he despatches people who get in the boss's way with skill and efficiency. The boss (Kim Young-cheol) trusts him so much that he asks Sun-woo to look after his mistress (Shin Min-ah), and to kill her if she is being unfaithful.

A Bittersweet Life posits what might happen if, after all those years, a frozen pysche such as Sun-woo's should suddenly start to melt. This would seem at first to be an overly romantic notion to throw into a Korean-style noir film, where the violence is gut-wrenching and the hero feels no qualms about putting his gun to a man's forehead and pulling the trigger. But the emotions that seep into Sun-woo's mind unleash a recklessness in him, that will later transform into fury once he senses that he has been betrayed.

The familiar stylistic traits of director Kim Jee-woon, seen before in A Tale of Two Sisters (2003), The Foul King (2000), and The Quiet Family (1998), can be spotted here in abundance, and yet he has never made a movie quite like this one. It feels nihilistic at times, and as in Oldboy -- which will surely be compared to this film countless times -- the violence is strong and innovative enough to become a topic of conversation. Mixed in with the cruelty is a bit of absurd, black humor in the middle reels, but not enough to lessen the heavy feel of the work as a whole. The end result is a visually stylish, cool film that is both very commercial (even though it underperformed in both Korea and Japan), and also complex enough to make it hard to pin down.

One way to approach this film is to simply revel in the details. I love the way Lee Byung-heon savors the last bites of his dessert before going downstairs to beat the pulp out of some rival gangsters who have wondered onto his turf. Perhaps in defiance of Korean critics who, after watching A Tale of Two Sisters, accused Kim of having a foot fetish, the director introduces his striking lead actress Shin Min-ah with a huge shot of her bare feet. I love the way Shin Min-ah's home is decorated (production designer Ryu Seong-hee is Korea's most famous; she also worked on Memories of Murder and Oldboy). And finally, I love the ending, even if I can't speak about it here. If the ending of A Tale of Two Sisters disappoints, the final shots of this film make up a sweet, indelible set of images. (Darcy Paquet)

Blood Rain, set in 1808, takes place on a small island with a technologically advanced (for its time) paper mill. The presence of the mill has spawned a bustling village, and given its townspeople a certain degree of wealth. With climate and trees perfectly suited for papermaking -- and a location remote enough to ensure both privacy and secrecy -- the island has established a profitable business in high quality paper, with trade routes stretching as far away as China.

It is on this isolated and largely self-autonomous island that a string of gruesome murders start to take place. It's not just the growing number of dead bodies, but the sickly innovative cruelty of the killing that breeds apprehension in Won-gyu (Cha Seung-won), a government investigator sent from the mainland to solve the case. Soon he discovers that the murders are linked to an incident seven years in the past, in which the former owner of the mill was executed for practicing Catholicism. The townspeople, for their part, are convinced that the dead man's ghost has come back for revenge.

It is on this isolated and largely self-autonomous island that a string of gruesome murders start to take place. It's not just the growing number of dead bodies, but the sickly innovative cruelty of the killing that breeds apprehension in Won-gyu (Cha Seung-won), a government investigator sent from the mainland to solve the case. Soon he discovers that the murders are linked to an incident seven years in the past, in which the former owner of the mill was executed for practicing Catholicism. The townspeople, for their part, are convinced that the dead man's ghost has come back for revenge.

Blood Rain (no relation to the famous Korean novel of the same title) is the odd fusion of a labyrinthine, complex narrative that calls for one's deepest concentration, and heaps of medieval, gory violence to sicken one's stomach. Straight-on shots of skulls being crushed and men being torn limb from limb are interspersed with ruminations on class relations in Confucian society, and applications of Western and Eastern science as a means of solving the film's central mystery. The end result is certainly unique and memorable, but sadly its central concept seems to work much better as ideas in a screenplay, than as images on celluloid.

This is not to say that the film isn't beautiful. The colors and cinematography, not to mention the rugged setting and elaborate set design, may indeed be the film's strongest element. But despite the fact that Lee Won-jae and Kim Seong-jae's screenplay has won praise within the local film community, the completed work struggles to hold all of the material contained within it. Major plot points are revealed by voiceover, rather than onscreen action, and to accomodate the film's two-hour running time, many ideas are simply thrown at the viewer, rather than being fully expressed. Partly as a result, much of the gory violence feels like compensation for a lack of drama.

It's a shame, because this project seemed to hold so much potential. It is the second feature of Kim Dae-seung (Bungee Jumping Of Their Own), who had previous experience in period filmmaking as an assistant director to Im Kwon-taek. Kim does have talent, and he employs some creative transitions in moving from scene to scene. Unconventional casting was also used in putting Cha Seung-won in the lead role, for his first non-comic effort since Libera Me (2000). However, lower marks go to the musical score by Jo Young-wook (Oldboy, Silmido), which features a distracting reworking of Rakhmaninov that manages to snuff out much of the film's poetry.

Speaking of snuff... please forgive me if I end this review with some comments about the chickens. According to traditional shamanist beliefs, chicken blood is supposed to provide some protection against malevolent spirits. Towards the end of the film, we are shown the depths of the villagers' panic in a scene where at least five real-life chickens get their heads chopped off in gory closeups (no time to close your eyes -- it's upon you in an instant). Clearly there was no CG imagery at work here. I imagine the crew simply cooked them up for lunch after the scene was shot, which makes you think: is there anything fundamentally different between this scene and a shot of a teenager munching down a chicken burger? But philosophical issues aside, the shots are so viscerally disturbing that they distract from a major plot twist that occurs just moments before, and it gives moralizing film critics (like myself?) something to latch onto instead of discussing the film itself. After all the ink spilled in newspapers worldwide over the fish in The Isle and the octopus in Oldboy, Korea is probably now going to become known as that country that likes to rip apart live animals in front of the camera. It's perhaps fortunate for the makers of Blood Rain that in the same month as its debut, Danish filmmaker Lars von Trier premieres his Manderlay at Cannes with a scene featuring a live donkey slaughtered on set. "If Lars can slice up a donkey," they might reasonably ask, "then what's wrong with a few chickens?" (Darcy Paquet)

(Addendum: a reader has now informed me that Von Trier elected not to include the scene with the donkey in his final cut, as he feared it might be too distracting)

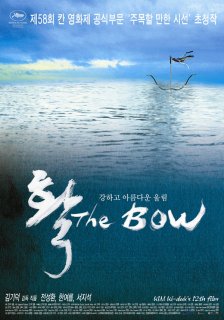

I should admit before starting this review that I've always had a hard time connecting on an emotional level with the films of Kim Ki-duk. People don't judge movies purely by objective criteria; they are also drawn to particular works because it says something to them personally. For me, the only films by Kim that have been able to do that are Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter and Spring (2003) and Samaritan Girl (2004).

The Bow, I'm sad to say, was an even tougher slog for me than usual, and a critical consensus seems to have emerged that it is not up to the level of Kim's other recent work. Manohla Dargis of the New York Times went so far as to call it "risibly bad", which is about as nasty a term as I can think of. So what went wrong with The Bow, anyway?

The story centers around a man in his sixties who has been raising a young girl since childhood on a ship that floats unanchored off Korea's western coast. Though the borders of her world are obviously quite limited, she seems happy, and the old man plans to marry her the day she reaches legal age. The two make their living by hosting fishermen aboard the boat, and also tell fortunes in a rather bizarre and dangerous fashion, by shooting arrows whizzing past the girl's head into a Buddhist painting on the side of the boat. (This method of fortune-telling appears to have been invented by Kim, though possibly inspired by the common practice of dropping a dart onto a spinning disc)

The story centers around a man in his sixties who has been raising a young girl since childhood on a ship that floats unanchored off Korea's western coast. Though the borders of her world are obviously quite limited, she seems happy, and the old man plans to marry her the day she reaches legal age. The two make their living by hosting fishermen aboard the boat, and also tell fortunes in a rather bizarre and dangerous fashion, by shooting arrows whizzing past the girl's head into a Buddhist painting on the side of the boat. (This method of fortune-telling appears to have been invented by Kim, though possibly inspired by the common practice of dropping a dart onto a spinning disc)

The film opens in striking fashion with a shot of the weapon that inspired the film's title. When fitted with an additional piece, the bow becomes a stringed instrument. Sadly, however, the instrument doesn't fit into the film's plot beyond providing for occasional mood music. The bow is utilized more often as a means of fending off lecherous fisherman from the young girl, who braves the dead of winter in a flimsy dress, and who (like all the women in Kim's films) is pretty gorgeous. Soon, however, a sensitive male college student shows up on board, and the old man discovers he's going to need more than a bow if he wants to keep the delectable young thing for himself.

One of Kim's most common approaches to storytelling is to set up an isolated or marginalized world (usually a physical space, but sometimes a way of life like in 3-Iron) that operates by its own elaborate set of rules and customs. Examples include the red-light district in Bad Guy, the lake in The Isle, the motel in Birdcage Inn, or the floating temple in Spring, Summer, etc... Part of the pleasure in watching his films comes in exploring and coming to understand these worlds and how they operate. For example, in The Bow we are shown how the girl and the old man defend themselves in a series of repeated scenes. First we are shown the man's skill with the bow, then we see how the girl's spatial knowledge of the boat and archery skills can serve as a second layer of defense. These scenes don't really add much depth to the human characters, but they characterize the "society" of the boat itself.

One of the problems with The Bow is that the basic setup is quite simple, compared to his previous films. The world of the floating temple in Spring, Summer... is just as artificially constructed as the boat in The Bow, but it contains more material, and gives us plenty to think about. The set of attitudes and customs which Kim presents in the film may not be "genuine" Buddhism, but they are worthy of notice in themselves.

In The Bow, however, once the ground rules are established, Kim has little left to fall back upon. The protagonists remain rather one-dimensional, and so the characters' psychology cannot properly sustain the narrative. Also, outside of the girl (Han Yeo-reum, having changed her screen name since appearing in Samaritan Girl) and the old man (Jeon Seong-hwan from Ogu), the acting is horrendous. Working with actors does not seem to be Kim's forte. He can give inherently talented actors space so that they excel (like Suh Jung in The Isle, Jo Jae-hyun in Bad Guy, or Kwak Ji-min and Lee Eol in Samaritan Girl), but he is unable to elevate the work of a less gifted cast such as we have here.

This is compounded by the fact that the two main characters do not speak to each other. It's true that one of Kim's strengths is to be able to tell stories using very little dialogue. The lack of dialogue between the leads in The Isle and 3-Iron worked well because these couples could communicate with each other emotionally, and the absence of words only accentuated their strange bond. However, in The Bow the old man and the girl spend much of the film growing emotionally more detached. Since they don't talk, the only way left for them to communicate is to trade angry stares, which they do, over and over and over again. In this way, the lack of dialogue comes across feeling more like a gimmick than an integral part of the film.

Despite all these weaknesses, the film probably could have been saved with decent music. However the score is sappy, not particularly melodic, and repetitive enough to make this 90-minute film a very frustrating experience. After three straight "hits", I think Kim has to file this in the "miss" category. (Darcy Paquet)

An expedition team led by Choe Do-hyung (Song Kang-ho) marches on toward the Antarctic Point of Inaccessibility, one of the most difficult places to reach on the planet Earth, and trodden upon only once by a Soviet team in 1958. Min-jae (Yu Ji-tae), formally trained in mountain climbing at Switzerland and in awe of the charismatic Do-hyung, is joined by the bookish navigator Young-min (Park Hee-soon), the rather thuggish but sharp communications expert Seong-hoon (Yun Je-moon), the genial cook Geun-chan (Kim Kyung-ik) and the electronics specialist Jae-kyung (Choe Deok-moon). When Min-jae discovers an old journal left by a British expedition 80 years ago, he begins to notice odd parallels between the journal entries and his team's experience.

Antarctic Journal had been a long-gestating pet project for the young director Im Pil-sung, whose short films including Baby (1999) and Souvenir (1997) received much critical kudos. I had been hearing rumors about the alleged brilliance of Im's screenplay (revised with input from director Bong Joon Ho and writer Lee Hae-joon) for several years. The big-budget production (8.5 billion won in total) set a new precedent for collaboration between Korean and New Zealand cinema industries. Despite the high expectation, however, the movie had a disappointing domestic run, contributing to the latest industry wagging about the decline of so-called star power in Korean cinema.

Antarctic Journal had been a long-gestating pet project for the young director Im Pil-sung, whose short films including Baby (1999) and Souvenir (1997) received much critical kudos. I had been hearing rumors about the alleged brilliance of Im's screenplay (revised with input from director Bong Joon Ho and writer Lee Hae-joon) for several years. The big-budget production (8.5 billion won in total) set a new precedent for collaboration between Korean and New Zealand cinema industries. Despite the high expectation, however, the movie had a disappointing domestic run, contributing to the latest industry wagging about the decline of so-called star power in Korean cinema.

Antarctic Journal has its share of problems but neither its stars nor its technical staff can really be blamed for them. While the character of Do-hyung is certainly not a stretch acting-wise for Song Kang-ho, he still does an excellent job in communicating the man's mental breakdown, mostly with subtly vacant stares and ill-timed smiles: there is no spittle-flying historionics. Yu Ji-tae presents a credible audience identification figure, whose faith in human reason and decency becomes severely tested. The rest of the team members are played by capable, theater-trained actors, making the most out of sometimes unevenly distributed dialogues and scenes.

Director Im Pil-sung, aided by DP Jeong Jeong-hoon (Sympathy for Lady Vengeance) and editor Kim Min-seon, makes striking use of the 2.35:1 scope screen. Sometimes two characters enter into a conversation while occupying extreme right and left corners of the screen, leaving a stretch of white space in the middle, signifying a distance that cannot be breached by communication. There are poetically beautiful but unnerving moments such as a beam of sunlight that pours into the makeshift tent, seemingly taking on the solidity of a pole made of golden glass. The film also includes some very impressive set pieces, most notably those involving ice crevices. Kawai Kenji's (Chaos, Ghost in the Shell) score is exceedingly effective in musically evoking the eerie atmosphere of Antarctica, simultaneously cold and intimate, and Dong-hyun's grim and relentless drive.

Regrettably, Antarctic Journal never makes up its mind about whether to stick to genre conventions or not. Is the film a new sack filled with old wine, an exotic update of true and tried horror cliches, perhaps a snowbound R-Point or a retread of John Carpenter's Thing (1982)? Or is it primarily a psychological thriller, the real horrors generated by the team members' paranoia and self-possession? Or is it a human drama, which explores the innate insanity of the "can-do" spirit that propel Korean "leaders" like Do-hyung toward his goal, with the bloody and torn bodies of his "family" strewn along the path? Antarctic Journal is a little bit of all of the above, but these elements never congeal into a coherent shape.

True, the fact that the audience does not receive sufficient "exposition" about what exactly is going on is in itself not such a serious problem. The real issue is that the film's mysteries are neither grounded in its characters nor anchored in its narrative design: we are given a lot of pieces of puzzle, which refuse to add up to a picture. To give but one example, what the heck is that white figure clearly recorded by a video camera but which no character seems to be aware of? What about the ghost from Do-hyung's past: is it really a dead spirit, or a projection of his guilty psyche? It eventually becomes tiresome to try to "figure" all these things out on your own. I can imagine many Korean viewers, expecting all the loose ends to be somehow tied up at the end, even if it involves a ridiculous deus ex machina ("It was all a dream! They never left the camp!"), groaning in frustration and getting up in a huff as the end credits roll.

Antarctic Journal contains enough impressive visuals and solid performances (not to mention Kawai's bone-chilling music score) to be worthwhile for viewers with an open mind and penchant for spectacles. Those who perhaps expect another emotionally satisfying genre hybrid in the manner of Save the Green Planet are advised to adjust your expectations lower. I personally wish Director Im had gotten rid of all the CGI "horror" effects and simply focused on Dong-hyun's character, exploring, Scorsese- or Herzog-style, his grand, foolhardy obsession and the ultimate abyss it leads into. This might have given this slick but flawed film a chance to kindle the softly glowing ashes of greatness at its core. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Every day I wallpaper my computer with a single image from a different South Korean film to help me suffer through the monotony of my day job. And I noticed something when I tile-d up my screen with the image of Hong Sangsoo's Tale of Cinema that is the left-center image at the top of this 2005 page. Because of the repetitive positioning of Hong's shot, this image creates dissonance when wallpaper-ed. Multiplied, the thick white line that divides our two characters appears to be a border, so Tong-su (Kim Sang-kyung - Memories of Murder and returning to work with Hong again after his exemplary portrayal in Turning Gate) and Yong-sil (Uhm Ji-won - Over The Rainbow, The Scarlet Letter) appear to be looking away from each other when in fact, as we know from the single image alone, they are looking at each other. (I actually brought over a colleague at my day job and asked her, 'Are the characters looking at or away from each other?'. She waffled in confusion - 'Looking away, wait, no, they're looking at each other, wait...?' - as I had with a cursory glance at my screen.) The Warholian multiples my computer affords results in an optical illusion of the 'Do you see a young or old lady?' variety. And what better way to demonstrate Hong's trope of the come-here/go-away ambivalence of his characters. Hong's characters are constantly struggling between either/or's - e.g., life/death, "clean"/"unclean", intimacy/isolation, love-me/love-me-not - that wallpaper their lives. And repetition of this single image underscores the repetition of single banal moments in Hong's films. This confusion around what constituted the border of the image highlights the tentative crossing, retrenching and re-crossing of borders, real and unreal, that Hong's characters engage in within each film and across his oeuvre.

The film begins with what we will later discover is a short film. This short film designates the first half of the larger film that is Hong's Tale of Cinema. This short film yet revealed to us as such involves a character named Sang-won (Lee Ki-woo - He Was Cool, Sad Movie) who happens upon an old classmate named Young-sil (played by the same actress as above). Sang-won's hesitation to meet up with Young-sil later eventually results in Sang-won ambivalently making a pact with Young-sil that they die together. When the second half emerges from the audience filing out of the short film we just saw along with them, we see the actress of the character in the short film, also named Young-sil, walking out and then we see Tong-su talking on his cell phone. We learn that the director of the short film, a character named Yi Hyong-su with whom Tong-su went to film school, is seriously sick in the hospital. Hyong-su's former classmates are meeting up for dinner to collect money to cover Hyong-su's hospital costs. On the way to and away from this dinner, Tong-su stalks Young-sil and repetitions of happenings "Like in the film" result.

The film begins with what we will later discover is a short film. This short film designates the first half of the larger film that is Hong's Tale of Cinema. This short film yet revealed to us as such involves a character named Sang-won (Lee Ki-woo - He Was Cool, Sad Movie) who happens upon an old classmate named Young-sil (played by the same actress as above). Sang-won's hesitation to meet up with Young-sil later eventually results in Sang-won ambivalently making a pact with Young-sil that they die together. When the second half emerges from the audience filing out of the short film we just saw along with them, we see the actress of the character in the short film, also named Young-sil, walking out and then we see Tong-su talking on his cell phone. We learn that the director of the short film, a character named Yi Hyong-su with whom Tong-su went to film school, is seriously sick in the hospital. Hyong-su's former classmates are meeting up for dinner to collect money to cover Hyong-su's hospital costs. On the way to and away from this dinner, Tong-su stalks Young-sil and repetitions of happenings "Like in the film" result.

Although not my favorite Hong film (I still go back and forth between The Power of Kangwon Province and Turning Gate), this film will still satisfy any Hong fan and annoy any Hong detractor. His second film in a row to compete in the main competition at Cannes, (the French title is Conte de Cinema), much has been said about Hong stepping away from his stationary camera to begin zooming in and out on his characters. Yet what I found most effective was his panning. In a scene in the first section where we pan towards a theater poster at which Sang-won is gazing, when we pan back, we expect to still see Sang-won staring at the poster. But instead he's gone, highlighting the elusive positions of Hong's characters who never stay grounded but run away from what's in front of them to later stumble upon the very people, situations and emotions they tried to escape. Outside of the new techniques, ever since Jeff Reichert's essay juxtaposing Turning Gate with Garden State in the Summer 2005 issue of the online journal Reverse Shot, I've been paying closer attention to Hong's use of color in the outfits of his characters. In the same image I discussed in the beginning here, Tong-su's dark blue (almost purple) jacket compliments Young-sil's cranberry scarf, adding a dissonating pleasure to the displeasure of that scene. The film score similarly presents contradictions, such as the hopeful melody that highlights the hopeless scene that ends the first half of this film. (By the way, the xylophonic score that begins the film is absolutely lovely.) Hong's use of vibrant colors and sounds to accompany otherwise discomforting scenes underscores the pleasure in the pain that his characters seem to endlessly repeat.

What struck me during this sixth film by Hong was how so many of the lines of dialogue, such as the subtitles "Why insist when it doesn't work?", "I couldn't go on doing nothing", or the dyad "I love you"/"You're talking rubbish", although well rooted in a specific context in a particular scene, could just as easily float through any of Hong's films and find just as believable a spot elsewhere to be spoken by any of his characters at any time. This is not a negative criticism, but part of what keeps bringing me back to Hong.

And speaking of criticism, when people ask me about my writing, I tell them although I write reviews and criticism, what I write are more like essays inspired by the film. And I love how Hong's films push me to write like this. I don't expect everyone to get as much out of Hong as I do. I know that some people find his constant returning to the "same" theme over and over again monotonous and elitist. (As if speaking for those critics during the opening scene, after Sang-won exhibits the "dodging the issue" behavior so important to Hong's men, Sang-won's older brother chastises Sang-won saying "That's typical!") But I have been watching and re-watching his films often - much easier to do thanks to the Kaurismäkian length to which his last two films have shrunk down -- because of the layers upon layers that keep building a treatise that I personally can't get enough of. Regardless of how "real" events portrayed in Hong's films might seem, I think of his films as not necessarily depicting real life but something deeper than that. They depict "philosophical life". And such is a life worth living. And one worth dying for as well. (Adam Hartzell)

Whereas some may see skateboarders as merely vandals and hooligans, I see them as performance artists, athletes and guides. Their performances work from dance in how they move their bodies and from music in how they manipulate their boards in ways that arouse percussive slaps, clicks, clacks, grinds, and carves upon the metal and concrete that makes a city. They are athletes in how they exploit, to create a word working off Pierre Bourdieu's use of "social capital", their kinesthetic capital, that is, the physical resources afforded them by their youthful bodies. From our teenage years to our twenties, our bodies allow for greater physical creativity since we possess greater energy and flexibility. Also, our bodies during this age span are better able to recover from injuries that at times result from such exploits. And skateboarders are guides in how they "read" cities. As Iain Borden illuminates in his wonderful book, a book I'd been wanting someone to write for years, Skateboarding, Space and The City: Architecture and the Body, skateboarders interact with a city and its structures differently than the rest of us. They reinterpret and reclaim spaces forgotten or ignored, they re-familiarize us with spaces so ubiquitous that we've blocked them out of our minds until skateboarders thrust these spaces back into our consciousness, and they revision what uses spaces encourage. They approach modern architecture ". . . unconcerned with architecture's historical purposes" (105). They are not interested in the entire structure, but pieces of it. They do not exploit the buildings as they were initially devised, as mazes to direct us through our day. Instead, they exploit the textures of a space. "This focus on texture gives skaters a different kind of knowledge about architecture, one derived from an experience of surfaces and material tactility" (194). Since skateboarders read a city through their bodies acting upon the city, they can help us read our cities differently if we'd only bother to learn from them like Borden has.

In-line skaters of The Aggressives variety can read cities similarly to skateboarders. And this is what I was hoping for from Jeong Jae-eun's second feature. In her masterful debut, Take Care of My Cat, Jeong brought us into the lives of five girls as they crossed into womanhood while negotiating a space for themselves within the opportunities and constraints available to them as young, Korean women in their city of Inchon. Along the way, Jeong provided us with many other fascinating observations, particularly how these young woman utilized technology in their relationships. Since in-line skating is also a technology, I was expecting a similar narrative use of this mechanical technology as Jeong afforded the computerized technology of cell-phones. Sadly, what I found instead were moments of promise that were never fully mapped out, nor as expertly intersecting, as they were in her debut.

In-line skaters of The Aggressives variety can read cities similarly to skateboarders. And this is what I was hoping for from Jeong Jae-eun's second feature. In her masterful debut, Take Care of My Cat, Jeong brought us into the lives of five girls as they crossed into womanhood while negotiating a space for themselves within the opportunities and constraints available to them as young, Korean women in their city of Inchon. Along the way, Jeong provided us with many other fascinating observations, particularly how these young woman utilized technology in their relationships. Since in-line skating is also a technology, I was expecting a similar narrative use of this mechanical technology as Jeong afforded the computerized technology of cell-phones. Sadly, what I found instead were moments of promise that were never fully mapped out, nor as expertly intersecting, as they were in her debut.

The Aggressives mainly follows the life of Chun Soyo (Cheon Jeong-myeong - R U Ready?), a "loner" who is alone in not thinking he's alone, and his new found friends, a group of in-line skaters. This crew includes a stock group of characters, the lothario, the comedian, etc., along with three other characters whose lives are a little more developed in the narrative. Gabba (Lee Cheon-hee - Ice Rain, A Good Lawyer's Wife) is the father figure of the crew and works at an in-line skating park. Mogi (Kim Kang-woo - Silmido, Springtime), which is Korean for "mosquito", is the rebel who just wants to skate for fun. For those who have seen Stacy Peralta's documentary about the second-wave of skateboarding, Dogtown and Z-Boys (2002), and the fiction feature that spawned from it, Lords of Dogtown (Catherine Hardwicke, 2005), Mogi would be comparable to the skateboarding legend Jay Adams. Mogi is held in similar high esteem concerning his skills, and similar low esteem when his I-don't-give-a-f*** attitude becomes intolerable. Soyo is positioned in between the father figure and the rebel during a scene where the two other characters have a fight. Soyo will mimic the style and attitude of each of these characters in front of a mirror in the next scene, underscoring the over-arching theme of the film: that we might fall a thousand times as we try to find the ways and means to our success. As there must be a love interest for whom these characters can also fall, (but, thankfully, this is not your typical portrayal of a teen movie love interest), we also have Han-joo (Jo Yi-jin). She aspires to direct an in-line skating video, so she follows these boys with camera in hands and skates on feet, just like Spike Jonze did before he got into John Malkovich's head.

Although aspects of this subculture are touched on, the artistry and the style (which are filmed very well), the skating for fun and identity, the battles with police and the public, etc., just as there are too many characters to juggle, there are too many themes that aren't molded into a coherent whole. Yes, one could argue that, since in-line skaters experience the city through bricolage, what Eithne Quinn explains in her book Nuthin' But a "G" Thing: The Culture and Commerce of Gangsta Rap as when ". . . individuals improvise responses to their environment, to what they have nearest at hand" (53), what seems incoherent is actually in sync with the subculture's aesthetics. But that, similar to what I wrote about the inferior film Looking for Bruce Lee (Kang Lone, 2002), would seem too much like rationalizing a greater significance out of this film than is justified. And although the sound design is exquisite when the skates meet the concrete, in stark contrast to Take Care of My Cat, the soundtrack is pretty lame compared to the former film's lush, perfectly syncopated, cell-phone-like melodies. In the end, like skaters to a city, I can take bits of enjoyment from pieces of this film, but Jeong doesn't seem to have taken care of this film as well as she did her debut. Still, she's entitled to hundreds more falls since she already found artistic success with her very first effort. (Adam Hartzell)

Mun-hee, a divorcee in her early thirties, has fallen in love with Hyun, in his last year of high school. Mun-hee is arrested and sentenced to 100 hours of community service for having sex with a minor, but upon her release Hyun meets her in front of the police station and they go to a love hotel for several more days of exhausting sex. Eventually, doubts begin to creep into Mun-hee's mind, and she declares that their affair is finished. Hyun is persistent, however, and soon their relationship enters a new phase.

At first Park Chul-soo's Green Chair sounds like a fairly straightforward tale of sex and the occasional pang of guilt, but it ends up being much more interesting than that. The film's first reel is highly explicit, and will turn off a lot of viewers, but later things settle down and we get to examine all the little details of Hyun and Mun-hee's unusual relationship, from Hyun's talent for cooking to Mun-hee's preference in mattresses. The film presents such details with warmth and humor, resulting in a nuanced, touching, and subversive love story.

At first Park Chul-soo's Green Chair sounds like a fairly straightforward tale of sex and the occasional pang of guilt, but it ends up being much more interesting than that. The film's first reel is highly explicit, and will turn off a lot of viewers, but later things settle down and we get to examine all the little details of Hyun and Mun-hee's unusual relationship, from Hyun's talent for cooking to Mun-hee's preference in mattresses. The film presents such details with warmth and humor, resulting in a nuanced, touching, and subversive love story.

As in many of his previous features, such as the grisly "cooking" movie 301,302 or the ob-gyn extravaganza Push! Push! , Park's direct, non-judgmental approach can be alienating for mainstream viewers. This turned into a problem for Green Chair when its investor, Hapdong Film, decided it was too bizarre to hold any commercial potential, and shelved it. That was in 2003, and it was a year and a half before interest expressed by festivals such as Sundance and Berlin managed to rescue it from obscurity.

Apart from Park's inimitable style of directing, Green Chair draws strength from its great cast. Suh Jung, best known from Kim Ki-duk's The Isle, brings a slightly unhinged vitality to the character of Mun-hee; while newcomer Shim Ji-ho plays Hyun as passionate and self-confident beyond his years. A special treat is the appearance of ultra-cool actress Oh Yun-hong (The Power of Kangwon Province) as Mun-hee's friend -- the warmth and camaraderie the three characters share is one of the film's key strengths.

Perhaps the most interesting part of Green Chair is its bizarre cocktail party resolution. I don't want to give away the details, but Park manages to address the tension created by our unconventional couple in a way that is both matter-of-fact and completely unexpected. The scene is also a fitting reflection of how face-saving and self-interest lie just beneath the surface of society's debates over morality. Despite his status as a veteran director, Park has always shown a youthful glee in poking at society's sore spots. Green Chair represents one of his most successful efforts in doing do. (Darcy Paquet)

Gang Hye-jung (Oldboy) plays a 27-year-old practicing teacher Hong, who is hit on by the schoolteacher Yu-rim (A startling turn by Park Hae-il, Memories of Murder). Initially, Hong is polite and demure to the point of idiocy against Yu-rim's lecherous advances, which quickly runs the gamut between workplace sexual harassment to outright date rape. However, the tables are turned in an unexpected way when Yu-rim accidentally runs into Hong's personal secrets, and when the details of their "love affair" are posted on the school's internet message board.

Rules of Dating was a sleeper hit of the early summer season, raking in more than 1.6 million tickets nationwide, and also generating some interesting and confused reactions from Korean viewers and critics (One review compared this film to an old Hollywood screwball comedy. Eh?). My reaction to Rules of Dating is similar to one I had to Im Sang-soo's Good Lawyer's Wife. Both films are sexually frank, morally challenging, quite funny and moving at times and driven by great performances by male and female leads. They are also not nearly as well put together or coherent in design as their defenders make it out to be, and neither is as "progressive" or "honest" as its filmmakers (in this case screenwriter Go Yun-hui and director Han Jae-rim) probably think it is.

Rules of Dating was a sleeper hit of the early summer season, raking in more than 1.6 million tickets nationwide, and also generating some interesting and confused reactions from Korean viewers and critics (One review compared this film to an old Hollywood screwball comedy. Eh?). My reaction to Rules of Dating is similar to one I had to Im Sang-soo's Good Lawyer's Wife. Both films are sexually frank, morally challenging, quite funny and moving at times and driven by great performances by male and female leads. They are also not nearly as well put together or coherent in design as their defenders make it out to be, and neither is as "progressive" or "honest" as its filmmakers (in this case screenwriter Go Yun-hui and director Han Jae-rim) probably think it is.

Rules of Dating is an undeniably entertaining and even thoughtful film, but let me be clear about one point: it is not a heart-warming romantic comedy. The complacent thoughts that drifted into my brain in first 35 minutes about which direction this movie was likely headed were rudely betrayed (to my pleasant surprise, I must say) by what happened next. Hong's eventual fate in the story can either be interpreted as the Triumph of Evil Witch or Just Desserts for All Concerned, depending on your own perspective, and not exactly following the battle lines drawn across the gender divide either.

Gang is wonderful as Hong, looking far less like an anime shojo and comfortably inhabiting the body of a harried and stressed working woman, but it is the transformation of Park Hae-il that will draw attention among fans. It is indeed difficult to believe that this is the same actor who played the lead in Jealousy Is Middle Name. As embodied by Park, Yu-rim (ironically named perhaps, since it can also mean "Confucian scholars") is a total, irredeemable slimeball. When he approaches Hong and plays "cute," with Park's patrician voice now stickily rolling off his tongue like golf balls greased in a vat of K-Y Jelly, you will be both laughing until your sides hurt and resisting the urge to throw up. The amazing thing is that, like Hong, Park's Yu-rim is a completely believable character in the Korean context, a fascinatingly disgusting (or disgustingly fascinating, take your pick) combination of taekwondo-kicking-under-the-blanket machismo, uncommunicative obtuseness, irresponsible immaturity and, yes, boyish charm.

On the other hand, the movie suffers from a certain narrowness of horizon, both stylistically and content-wise. Director Han does a superb job with the actors but unfortunately abuses that super-trendy, nausea-inducing hand-held style (that looks as if "the cameraman is jerking off or something," as Roman Polanski reportedly once said) as well as the jump cuts that snip away in the middle of a character's action. The screenplay cried out for the kind of expressionist cinematic technique counterpointing the absurdity and nastiness of the superficially "funny" exchanges, but as it is presented, the mise en scene becomes repetitive and, eventually, tiring (I assume this attention-deficit editing style was not suggested by the veteran editor Pak Kok-ji). And the movie appears to ultimately hedge its bets regarding the possibility of a real romance brewing out of such politically and emotionally charged set-ups, involving sexual abuse, invasion of privacy and manipulation of ethics codes. When Lee Byung-woo's pleasant score accentuates the romantic mood, we are left unsure whether to take it at face value or in an ironical way, as a snickering commentary on the impossibility of true romance.

Rules of Dating is a gutsy film, very funny with nasty undertones (in that regard perhaps closer to a Hong Sangsoo film in spirit than the aforementioned Jealousy Is My Middle Name). It is best appreciated by those not easily offended and getting tired of mock-CF "rom coms" with the disease flavors of the months, and will make good fodder for post-screening discussion among friends and couples. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Here is an old Korean riddle: What is the monster that opens its mouth wide and gobbles up your foot every morning? A shoe, of course.

Sun-jae (Kim Hye-su, Hypnotized, YMCA Baseball Team), an eye-doctor-turned-housewife, finds her cold, inattentive husband (Lee Uhl, Samaritan Girl, The Addicted) cheating with a younger woman. Abandoning her affluent suburban life, she moves into a decrepit studio apartment with her six-year daughter Tae-soo (Pak Yeon-a). Preparing to resume her medical career, Sun-jae is befriended by an interior designer In-cheol (Kim Seong-su, Sweet Sex and Love). Her life, however, plunges into an abyss of paranoia and nightmare after she picks up a pair of pink shoes (Hans Christian Andersen's cruel fairy tale Red Shoes, on which the film's premise is obliquely based, has mostly been known as Pink Shoes in Korean. Don't ask me why) lying about inside a subway car. Not only have this pair of shoes apparently performed wholly unnecessary amputation surgeries on the select individuals foolish enough to don them, they also become objects of unhealthy obsession for the ballet-dancing tyke Tae-soo. Unfortunately, this obsession is shared by Sun-jae. Soon mother and daughter are screeching and pulling each other's hair over the possession of the high-heeled monstrosity, which turns out to have an awful backstory reaching back into the colonial period.