Documentaries

From left: "Mudang", "Family Project: House of a Father", "Haengdang-dong People", "This is Not Seo Tae-ji"

The history of Korean independent documentaries is short -- a legacy of the film policy enforced by Korea's military government that made it illegal for non-registered producers or companies to make films. Apart from documentaries produced for television (which mostly fall outside the scope of this page), independent documentaries first began to surface only in the late 1980s. Kim Dong-won's Sanggye-dong Olympics, about the forcible relocation of slum residents during construction for the Olympics, is considered by many to represent the first major work of the Korean documentary movement.

Documentaries in the late 1980s and early 1990s, often made at the risk of arrest, mostly fell into the category of political activism. Groups of activists came together and formed documentary collectives to provide an alternative view of reality and push for social change. Often the documentaries would list no "author" or director beyond the collective itself.

Lee Hyun-jung in her essay "The 'I' in the Korean Documentarist" (published in Drowning in a Thousand and One Waves by the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival) notes that from the mid-1990s, Korean documentaries began to undergo a significant change. Directors began to refer to themselves as "I", acknowledging their role in the making of the documentary. Rather than presenting an objective "truth", directors would show clearly their role in creating the documentary and shaping/interpreting what is represented. One of the first directors to introduce this trend was Byun Young-joo in her remarkable documentaries about comfort women beginning with The Murmuring (1995).

Korean documentaries retain a strong focus on politics, with a large percentage focusing on labor issues. Nonetheless, subject matter has increasingly diversified in recent years to embrace issues like shamanism (Mudang: Reconciliation Between the Living and the Dead), gender and sexuality (Being Normal), and overseas Koreans (Sky Blue Hometown, And Thereafter). The advent of digital video has done a lot to increase the number of films being made as well.

It is rare for Korean documentaries to receive a theatrical release -- it usually only happens about once a year or two. They can most easily be viewed at local festivals such as Pusan (PIFF), Jeonju (JIFF), the Women's Film Festival in Seoul (WFFIS), or the Seoul International Documentary Film Festival (SIDFF), as well as at a special archive devoted to Korean documentaries in downtown Seoul. A small number are even coming out on DVD, hopefully heralding the day when people in any country can get easy access to the best work produced by Korea's documentarists.

Reviewed below: My Own Breathing (1999) Being Normal (2002) Mudang: Reconciliation Between the Living and the Dead (2003) Women's History Trilogy (2000-4) My Korean Cinema (2003-5) Repatriation (2004) One Day on the Road (2006) Our School (2007) Out: Smashing Homophobia Project (2007). Planet of Snail (2012). My Fair Wedding (2014) An Omnivorous Family's Dilemma (2014) Crossing Beyond (2018) In the Absence (2018) Untold (2018).

| Rank | Director | Seoul Admissions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Our School (2007) | Kim Myeong-jun | 32,154 |

| 2 | Between (2006) | Lee Chang-jae | 24,081 |

| 3 | Repatriation (2004) | Kim Dong-won | 19,202 |

| 4 | Bisang (2006) | Im Yu-cheol | 13,549 |

| 5 | Mudang (2003) | Park Ki-bok | 13,474 |

| 6 | The Murmuring (1995) | Byun Young-joo | ~10,000 |

| 7 | My Own Breathing (2000) | Byun Young-joo | ~5,000 |

| 8 | Making Sun-Dried Red Peppers (2001) | Jang Hee-sun | 550 |

| 9 | Annyoung, Sayonara (2005) | Kim Tae-il, Kato Kumiko | 550 |

| 10 | On the Road, Two (2006) | Kim Tae-yong | 479 |

This documentary by Byun Young-joo is the final chapter of a trilogy documenting the present and past lives of "comfort women" who were abducted and forced into sexual servitude by the Japanese army in World War II. Byun's efforts have lent a significant push to the women's demands for a formal apology and compensation from the Japanese government. At the same time, the films have drawn praise for their aesthetic and emotional power.

The first film in this series, entitled The Murmuring (1995), has become one of the most acclaimed documentaries in Korea's history. Byun states that when she first contacted a group of comfort women and asked if she could film them, they refused emphatically. It was only after living together with them for one year that the director gained their trust and permission to make a film. This first documentary portrays the women leading their weekly protests at the Japanese embassy and fighting to overcome the sense of shame that has been planted within them and reinforced by an uncaring public.

The first film in this series, entitled The Murmuring (1995), has become one of the most acclaimed documentaries in Korea's history. Byun states that when she first contacted a group of comfort women and asked if she could film them, they refused emphatically. It was only after living together with them for one year that the director gained their trust and permission to make a film. This first documentary portrays the women leading their weekly protests at the Japanese embassy and fighting to overcome the sense of shame that has been planted within them and reinforced by an uncaring public.

Habitual Sadness (1997) was initiated at the request of the women, who asked that Byun film the last days of a group member who had been diagnosed with cancer. In this film we see the women gaining self-confidence, eventually moving behind the camera themselves to utilize the medium of film as a means of both protest and healing.

In My Own Breathing, we are introduced to a new character who was taken forcibly into service at 14 years old. In the picture above, she is interviewed by another former comfort woman, who was shown in earlier films and who underwent many of the same experiences.

The director understands that as heart-rending as the accounts of forced prostitution may be, we can only come to understand these women by focusing on their present. Some of the most shattering moments in the film come about unexpectedly; small details that reveal the humor and personality of these women who survive years after the wreckage of their youth. In this manner the documentary leads us to see the crimes as much more than tragic abstractions; instead we witness the effect it has had on these women's lives, and we imagine the horror of such violence inflicted upon those whom we know and love. (Darcy Paquet)

My Own Breathing ("Sumgyeol - Najeun moksori 3"). 77 min., 35mm, color, optical mono. Directed by Byun Young-joo. Produced by Shin Hye-eun. Cinematography by Byun Young-joo, Han Jong-gu. Editing by Park Gok-ji. Screened at the 1999 Pusan International Film Festival. Released in Korea on March 18, 2000. Seoul admissions: 5,000.

Walking hand in hand with the rise of Korean Cinema has been a rise in the presence of sexual minorities in Korean films. For the most part, these portrayals are quite respectful of difference while still being honest about the societal pressures that still force into the closet those Koreans who don't fit snugly into heterosexual nomenclature. (I'm thinking of such films as Memento Mori, Wanee & Junah, and Road Movie when I make this statement.) Choi Hyun-jung's student project, Being Normal, continues in this tradition of Queering Korean Cinema.

Being Normal documents the friendship between Choi and her roommate and classmate, J, a Hermaphrodite. With both male and female sex organs, J's mere existence challenges the binary of male/female into which we force an immensely diverse field of human experience. As Choi gets to know J, J slowly shares his world and what it's like for him to explain himself to others who don't like their dichotomies split any further. Much of J's struggles are universal to Intersexuals, (the wider term that encompasses all those whose bodies challenge long held assumptions about biological norms), regardless of country of origin. However some aspects illuminated here are specific to South Korea, such as how J's experience almost complicated an Uncle's pursuit of a male child and the required military service for all males.

Being Normal documents the friendship between Choi and her roommate and classmate, J, a Hermaphrodite. With both male and female sex organs, J's mere existence challenges the binary of male/female into which we force an immensely diverse field of human experience. As Choi gets to know J, J slowly shares his world and what it's like for him to explain himself to others who don't like their dichotomies split any further. Much of J's struggles are universal to Intersexuals, (the wider term that encompasses all those whose bodies challenge long held assumptions about biological norms), regardless of country of origin. However some aspects illuminated here are specific to South Korea, such as how J's experience almost complicated an Uncle's pursuit of a male child and the required military service for all males.

As evidenced in one of the sentences in the above paragraph, the English language presents difficulties when talking about Intersexuals. Which possessive pronouns do I use to describe J when I need to avoid grammatical gymnastics? Is "he" or "she" "he" or "she"? Will the grammar police just learn to deal with the natural state of language change and allow us to appropriate the third person plurals, "they," "their," and "them" for reasonable use here? Similar problems will be present for the viewer who knows Korean. If J is older than Choi, (which I haven't been able to confirm), is J Choi's "Oppa" or "Onni"? I've chosen to use 'he' because that's what J eventually chooses. And this brings up one of the most discomforting aspects of this film, the voyeurism. For, as J's outward appearance changes, we the viewers are privileged an opportunity to stare at J's difference and watch while he transforms into someone whose outward attire signifies someone more biologically male, although the final J shown to us conveys more of an androgynous look such as we often find in male pop-stars for the teeny-bopper set. Understandable considering the obstacles against which J must battle, for a brief time J had asked that this film not be shown, waning back and forth on his comfort level regarding the finished product.

Choi's choice to turn the camera on herself appears to be an effort to address the inherent voyeurism in this documentary. She makes herself the occasional object of her own gaze. And in so doing, we not only see J change, but Choi. One of the more interesting moments for me is when J challenges Choi's womanhood, telling her she's not a woman. Choi's reaction to this doubt in her femalehood is swift, end of discussion. Yet, it's after J's joking challenge that I began to notice Choi taking on more feminine signifiers in her appearance later in the film. Such a moment causes us to realize how often each of us engages in similar perpetrating of our own image. (That is, if we are comfortable challenging our own attachments to gender.) And, later, when rifts emerge in their friendship, it is commendable that Choi chooses to leave in the scenes where her reactions might be seen as less than exemplary.

Just as it's important not to deny the Queerness of this documentary, it's important to note how this film is also simply about friendship. Choi and J have their fun and intimate moments as well as their disagreements and betrayals. And isn't every documentary an expose on truth showing how we aren't always honest with our selves and our own personal stories? And when one does not fit in with society's arbitrary norms, it can be understandable how hesitantly or roundabout we come to our truths, if we ever come to them at all. (Adam Hartzell)

Being Normal ("Pyeongbeom-hagi"). 58 min., DV, 4:3, color, mono. Directed by Choi Hyun-jung. Produced by Park Ju-yong and Lee Min-jin. Cinematography by Choi Hyun-jung. Editing by Choi Hyun-jung and Lee Ik-sang. International sales by Film Messenger (master@filmmessenger.com). Winner of the Critics' Award at the 2002 Hong Kong IFVA.

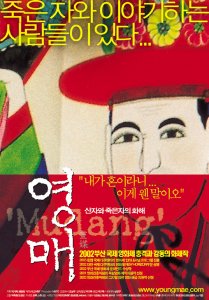

![]() Mudang: Reconciliation Between the Living and the Dead (2003)

Mudang: Reconciliation Between the Living and the Dead (2003)

Park Ki-bok's documentary Mudang: The Reconciliation of the Living and the Dead is a successful work because it provides a valuable experience for viewers from widely different backgrounds. For those new to Korean Shamanism (Mu), the basic structure of the documentary allows for easy comprehension. Forms of Korean Shamanism are, for the most part, separated by the Han River. Shamans in cities and villages to the South of the Han and East of the Taebaek Mountains, such as Jindo Island, are primarily Saseummu ("Hereditary Shamans") who have their status passed down through familial lineage where the women become shamans and the men ritual (Gut) musicians. Whereas in cities North of the Han and Central Korea, such as Seoul, Gangshinmu ("Possessed Shamans" or "Spiritual Shamans") obtain their standing after claims of possession by a master spirit have been confirmed by other Gangshinmu. Gangshinmu also engage in fortunetelling and have more recently crossed the Han River to perform their rituals in the South, but the Saseummu are not known to have traveled North. (The DVD has wonderful extras, in English along with Korean, which help viewers, such as this one, clarify the terms.)

For the viewer more well versed in Korean Shamanism, Mudang is still immensely useful. Encompassing many different rituals from many different regions, one can witness each ritual in comparison with its sister ritual from North and South of the Han. We are also privileged to share witness to personal rituals of a particular family and the relationship their Gangshinmu establishes with them.

For the viewer more well versed in Korean Shamanism, Mudang is still immensely useful. Encompassing many different rituals from many different regions, one can witness each ritual in comparison with its sister ritual from North and South of the Han. We are also privileged to share witness to personal rituals of a particular family and the relationship their Gangshinmu establishes with them.

And for those with little interest in Shamanism, the film provides wonderfully intimate moments in the life of towns and villages less prevalent in Korean Cinema. With raw footage of the everyday lives of these villagers, we are presented snapshots of how South Korea's Modernization appears to have passed some people by. Much discussion is made of the Korean-specific concept of Han, an elusive concept to non-Koreans, but roughly translated in this documentary as bitterness or sorrow across generations which it is the job of Shamans to reconcile. The documentary also allows the opportunity to hear personal philosophies and histories from several elderly Korean women with all their raw edges and humor. Considering that most Shamans are women, interesting matriarchal moments of authority arise within a primarily patriarchal culture, such as the scolding men receive during a Jinjeok Gut (ritual of a Shaman's ancestors).

Director Park appears to have come to this project with a deep respect for his subjects as if they are his teachers. His style is as warm as the tone of the voice of the narrator, Sol Kyung-gu. Enough narrative is provided of a circular sort to keep this documentary from falling into the incoherent collage of images that too many documentaries fall victim to. Having situated the frame slightly to the upper left hand corner so as to provide, on a strip of black on the right side of our field of vision, hangul-ed explanations and translations for better understanding of the words spoken by those with heavy regional dialects or voices affected by paralysis, we are asked to watch this documentary with our realities temporarily a skewed. A perfect design choice since we are stepping into a people's supernatural beliefs.

As an Agnostic myself, I do not leave this film believing any more about the supernatural than I began with. Rather than illuminate how basic Reason can challenge moments in the film that purport possession of supernatural powers, since such moments could be seen as almost horror-film-like, major plot points, let me just drop that basic knowledge of coin flips, gossip and familiarity amongst community members, and psychosomatic effects of grief can explain a lot here. However, concerning the latter, I can see the role Shamans have in helping families grieve loss and accept the truths that life brings. And I am also left with some powerful images, such as the elaborate rituals and the disturbing rites that involve animal sacrifice (yes, animals were harmed in the making of this film) or tongues "caressing" blades (yes, tongues were harmed in the making of this film, but tongues are the fastest healers of any of our organs, so less worries there). But the images that I found most impacting were those of everyone in the villages dancing, indirectly celebrating community in contrast to the worries confessed by the Shamans about the loss of their arts, the loss of their traditions. Joy and sadness are better acquaintances than we realize at times. (Adam Hartzell)

Mudang: Reconciliation Between the Living and the Dead ("Yeongmae: san jawa jugeun ja-ui hwahae"). 100 min., 35mm, 1.85:1, color/b&w, Dolby SRD. Directed by Park Ki-bok. Produced by Cho Sung-woo. Cinematography and editing by Park Ki-bok. Narrated by Sol Kyung-gu. International sales by Music & Film Creation Co., Ltd. (sungwoocho@digital-musicfilm.com). Winner of the Woonpa Award for Best Documentary at the 2002 Pusan International Film Festival (in an earlier cut). Re-cut and released in Korea on September 5, 2003. Seoul admissions: 13,474. Nationwide admissions: 15,714.

![]() Women's History Trilogy (2000-4)

Women's History Trilogy (2000-4)

Eventually, we come upon an image of two windows. Each of these panes is sectioned into four panes. All but one of the panes is white. The other reveals the action or inaction occurring outside. It is but one piece of the story, one introduction to more multi-paned lives. Since women's stories so often go overlooked, this image presents to me a wonderful summary of Kim So-young's Women's History Trilogy.

"Koryu: Southern Women/South Korea" begins with a story about Kim's own grandmother who grew up in Kosung. Kim traveled to this village to return to her grandmother's history. Her grandmother wrote eulogies for women of the village, which was a limited opening for women to write about their lives since Confucian gender constraints otherwise silenced women's voices. Kim's camera will soon slowly travel through the lives of several women who have simple stories to tell of much more complicated lives.

Kim's intent is to extend the Sino-Korean word koryu, which primarily means a temporary abode, to embrace those who live marginalized lives, such as the no-woman's land of patriarchy. Refusing to eulogize by providing hope for her sisters, in the feminist sense, Kim later takes us to meet other woman so that they can tell snippets of their own stories. A Chinese immigrant who runs a Chinese restaurant and wishes not to impose barriers on her daughters' future, a teahouse owner whose family circumstances kept her "trapped" from pursuing music study overseas, and the aspiring director Oh Yoon-jung who is Kim's "script girl" during this project. Each of the stories portrayed are different panes of a larger window on Korean women's lives.

Kim's intent is to extend the Sino-Korean word koryu, which primarily means a temporary abode, to embrace those who live marginalized lives, such as the no-woman's land of patriarchy. Refusing to eulogize by providing hope for her sisters, in the feminist sense, Kim later takes us to meet other woman so that they can tell snippets of their own stories. A Chinese immigrant who runs a Chinese restaurant and wishes not to impose barriers on her daughters' future, a teahouse owner whose family circumstances kept her "trapped" from pursuing music study overseas, and the aspiring director Oh Yoon-jung who is Kim's "script girl" during this project. Each of the stories portrayed are different panes of a larger window on Korean women's lives.

The highlight of this trilogy for me is definitely "I'll Be Seeing Her: Women in Korean Cinema" (2002), a collage of images from films past and present. Kim is a film scholar and has written many books and articles on South Korean cinema (go check out her citations in our bibliography elsewhere on this site), and this documentary is her attempt to "translate" her books into film. So many of these films from the past are ones I desperately wait for the opportunity to see, and the images and commentary here by Kim generate even greater anticipation. We witness the first screen kiss in a Korean film, The Hand of Destiny (Han Hyung-mo, 1954), which newspapers reported caused gasps from the housewives present at screenings. This first kiss is presented to us after the coachman's hand is rejected by the woman he is courting in The Coachman (Kang Dae-jin, 1961).

This documentary is very much an audience study, specifically a study of women as spectators. Several women are interviewed throughout about how they watched movies, what was most memorable to them. Everyday moviegoers such as merchant women in Jagalchi and Kukje markets are interviewed, many finding much to say about Bitter, But Once Again (Jung So-young, 1968). Not-so-everyday movie-goers such as artist Yoon Suk-nam, actress/director Choi Eun-hee, and Night Journey actress Yun Jeong-hee are asked for their memories as well. Yun Jeong-hee has great praise for present day actresses Shim Eun-ha and Bae Doo-na. (Bae is also interviewed in this documentary. She lets us know her most memorable scene is the one where she is chased by the homeless man through the apartment in Bong Joon-ho's Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000).) Bae's stellar acting ability is underscored by Yun when she compliments her - "Bae Doo-na owns her world."

Each segment, each film clip, each commentary brings to my lips questions I wish I could ask Kim and all those involved in the making of the films presented. The only problem with this particular documentary is that so many of the topics touched on demand greater exploration. When she accuses Oasis (Lee Chang-dong, 2002) and Adada (Im Kwon-taek, 1987) of being purely male fantasy projections, she lost me somewhat. I feel both of these films are much more complicated than her brief statement alludes, particularly when looking at them from an understanding of film portrayals of disability. But that's another history that needs just as much of an opportunity to present itself. I cannot expect Kim, in such brevity, to address every angle. So I must simply sit with the thoughts she provokes, such as her interesting take on the "vanishing" of Korean women through the emergence of multiple non-Korean women portrayals, such as North Korean women in Shiri (Kang Je-gyu, 1999), the Swiss-Korean in JSA (Park Chan-wook, 2000) and the Chinese woman in Failan (Song Hae-sung, 2001). Kim ends the film touching on women who are expanding a woman's place in cinema. And this documentary definitely inspires further evidence of where it ends. That is, you cannot help but leave with greater interest in analyzing and improving the portrayals of women in cinema and opening up further venues for women to tell their stories.

The final installment, "new women: her first song" (2004), revisions the legacy of artist Na Hae-suk (1896-1948). A painter of warm, lush, impressionistic, Western-style landscapes and writer of poetry and travelogues, Na was one of the first Korean women to travel throughout Europe. While in France, she found herself entranced by the open intimacies of the French couple she stayed with. Na would later negotiate for a Western marriage and greater freedoms in her own marriage. Her life would be chronicled in Kim Su-yong's 1978 film Fire Bird, but Kim So-young here looks at her place in the feminist movement in South Korea of the past, present and future, by having other Korean artists and scholars comment on the influence of Na's art on their own work as well as their personal interpretations of feminist art. Kim also connects Na's impact to the wider ap'ure kol ("New Women" movement), or Modern women repositioning themselves away from traditional cultures, emerging throughout East Asia at the time, bringing in examples from China and Japan as well. However, Kim is also reclaiming the ap'ure kol as examples of early feminists since, as Jinsoo An has noted, the ap'ure kol, embodied in South Korean film and literature as war widows and yanggongju (prostitutes), were often positioned as "morally corrupt" to encourage women to take up the "virtuous mother" roles that Confucianism demanded and an emerging, indigenous, syncretic Christianity rearticulated. Similar to "I'll Be Seeing Her", Kim brings in well-placed film images to underscore her arguments and makes further use of cut-out animation.

The final installment, "new women: her first song" (2004), revisions the legacy of artist Na Hae-suk (1896-1948). A painter of warm, lush, impressionistic, Western-style landscapes and writer of poetry and travelogues, Na was one of the first Korean women to travel throughout Europe. While in France, she found herself entranced by the open intimacies of the French couple she stayed with. Na would later negotiate for a Western marriage and greater freedoms in her own marriage. Her life would be chronicled in Kim Su-yong's 1978 film Fire Bird, but Kim So-young here looks at her place in the feminist movement in South Korea of the past, present and future, by having other Korean artists and scholars comment on the influence of Na's art on their own work as well as their personal interpretations of feminist art. Kim also connects Na's impact to the wider ap'ure kol ("New Women" movement), or Modern women repositioning themselves away from traditional cultures, emerging throughout East Asia at the time, bringing in examples from China and Japan as well. However, Kim is also reclaiming the ap'ure kol as examples of early feminists since, as Jinsoo An has noted, the ap'ure kol, embodied in South Korean film and literature as war widows and yanggongju (prostitutes), were often positioned as "morally corrupt" to encourage women to take up the "virtuous mother" roles that Confucianism demanded and an emerging, indigenous, syncretic Christianity rearticulated. Similar to "I'll Be Seeing Her", Kim brings in well-placed film images to underscore her arguments and makes further use of cut-out animation.

Kim's trilogy is a throught-provoking investigation into the lives of Korean women. From artists to images to oral histories, we are introduced to Korean women's history, we are motivated to demand more complex images of women from our films, and we begin to wonder if woman is the future of film. (Adam Hartzell)

Women's History Trilogy includes the documentaries Koryu: Southern Women, South Korea ("Georyu," 2000, 83min.), I'll Be Seeing Her ("Hwangholgyeong", 2002, 50min.), and new women: her first song ("Jiljuhwansang," 2004, 50min.). DV/digibeta, color/b&w. Directed by Kim So-young. Released on DVD in 2005 with support from the Korea Foundation.

Kim Hong-joon might prefer that My Korean Cinema not be here in the Documentary section of Koreanfilm.org. Kim sees a "documentary" as an objective observation of an event. And Kim could hardly be objective in this personal essay about the Korean film industry since the greater part of his life has been devoted to the industry in one capacity or another. This man, whom Korean film scholar Kyung Hyun Kim has called a "Renaissance Man," has been, among many positions, a director (La Vie En Rose, 1994; Jungle Story, 1996), a scholar (a professor at the Korea National University of Arts and author of a book of film criticism), a host of a TV show on classic Korean cinema, the founder of the Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival, a member of the Korean Film Council, and even an extra with an accidental speaking part in Fly High, Run Far, Kaebyok (1991) and Low Life (2004), both by Im Kwon-taek. But the documentary takes many forms and can never be totally objective anyway, so I'm comfortable with including it here, but I will use a term closer to Kim's liking to describe this project -- 'personal video diary.'

Kim, like many involved in the Korean film industry of his generation, wanted to rediscover the cinematic history that South Korea had forgotten. When conveying his ideas regarding this project to director Hong Sangsoo, Hong accused Kim's initially distant approach to the topic as 'not being honest.' Hong told Kim to 'open up', a point Kim emphasized when retelling the story to me by simulating the ripping off of the clothes covering his torso, as if he were Clark Kent revealing a Superman 'S' underneath his dress shirt. Hong's guidance jumpstarted Kim's project, telling Kim honesty is 'the only way you will reach people.'

Kim, like many involved in the Korean film industry of his generation, wanted to rediscover the cinematic history that South Korea had forgotten. When conveying his ideas regarding this project to director Hong Sangsoo, Hong accused Kim's initially distant approach to the topic as 'not being honest.' Hong told Kim to 'open up', a point Kim emphasized when retelling the story to me by simulating the ripping off of the clothes covering his torso, as if he were Clark Kent revealing a Superman 'S' underneath his dress shirt. Hong's guidance jumpstarted Kim's project, telling Kim honesty is 'the only way you will reach people.'

Another reason why Kim wouldn't want this review to be here has nothing to do with the section it resides in. Kim would rather not have you told about the film images contained within his personal video diary. He'd rather have you experience the images and then seek them out yourself. But artists and scholars put their work out into the world and it will rarely return as they fully intended it, and so the saga continues here on Koreanfilm.org.

The personal video essay consists of, at this writing, five episodes. Kim episoded them because the prequels of the Star Wars franchise had begun around the time he started this project. The first episode "My Chungmuro" surveys his beginnings in the film industry, looking first at his time as production assistant on Fly High, . . . where he "learned by watching and keeping an eye on what to do" and finishing with his memories of the Daehan Cinema of his youth and where it doesn't stand now. The second episode discusses the impact March of Fools (Ha Kil-jong, 1975) had on him since he was a college student at the same time as the college students portrayed in the film. He recalls how his first screening was one of disappointment, seeing the film as an over-simplification of the protest movement and the ending as overly sentimental. But when Kim saw the restored version that included all the salvageable scenes cut by the censors, he witnessed a significant shift in tone. But rather than lash out at the censors as so many might when discovering this, he found himself curious about the censors, wanting to hear their stories, wanting to hear their reasons for each stately edit. Episode three is entitled "Smoking Woman" and that is exactly what it is, images of women smoking and how such was used as shorthand for character development. This scene closes with what should stand as the greatest filmic representation of Magritte's masterpiece of painted epistemology, This Is Not a Pipe, a scene from a film by Kim Ki-deok that none of the Korean film scholars at the screening I attended could recall. Episode four "KINO 99" has Kim showing up at the offices of Kino magazine while the employees put the finishing touches on the final issue, #99. But don't expect a sad tale of the end of an era, Kim shows us that things can just as easily get started at the end. Episode five "Geum-soon!" is a juxtaposition of aural and filmic images from different times, but a similar place, that will have you rushing to your nearest Korean film-loving ajumma or ajeossi to help you understand the wonderful collage you just witnessed. (Pictured below is Han Hyeong-mo's Double Curve of Youth (1956), which figures prominently)

For those of us with strong interests in Korean cinema and its history, Kim's professional-is-personal project is an utterly delightful viewing experience. You will find yourself even more anxious to see even more classic Korean films than you already have itemized on your own personal list of must-sees. Particularly powerful for me are episode two and five, the former for what the juxtaposition of cut and uncut scenes illuminates about Ha's original intent and the power all states of censorship have to remove a film's potency, and the latter for its experimental 'what-the-hell-is-this?' moment that simply triggers your curiosity like an intellectual elixir. However, Kim's insistence to not go back and touch-up these episodes will limit its reach. Many will find the production job shoddy considering what they expect from Korean cinema these days, particular Episode 4 at Kino's office. This personal video diary is really a secondary source of primary texts for those with a strong scholarly interest in Korean cinema and for those whom the video diary is just as personal. That is, those from the times and places discussed for whom such moments resonate as strongly as they do for Kim.

For those of us with strong interests in Korean cinema and its history, Kim's professional-is-personal project is an utterly delightful viewing experience. You will find yourself even more anxious to see even more classic Korean films than you already have itemized on your own personal list of must-sees. Particularly powerful for me are episode two and five, the former for what the juxtaposition of cut and uncut scenes illuminates about Ha's original intent and the power all states of censorship have to remove a film's potency, and the latter for its experimental 'what-the-hell-is-this?' moment that simply triggers your curiosity like an intellectual elixir. However, Kim's insistence to not go back and touch-up these episodes will limit its reach. Many will find the production job shoddy considering what they expect from Korean cinema these days, particular Episode 4 at Kino's office. This personal video diary is really a secondary source of primary texts for those with a strong scholarly interest in Korean cinema and for those whom the video diary is just as personal. That is, those from the times and places discussed for whom such moments resonate as strongly as they do for Kim.

Finally, there is one last reason why this project should not be reviewed in any section of Koreanfilm.org. The project is not done. Kim plans to complete 3-5 more episodes this year alone and he doesn't plan to stop there. But just like Kim, I'll document his document as it continues, awaiting the episodes to come just as I await opportunities to see the classic Korean films contained within. (Adam Hartzell)

My Korean Cinema ("Na-ui hangung-yeonghwa"). 5 episodes, DV/video, color/b&w. Directed and narrated by Kim Hong-joon. Screened at 2003 Vancouver International Film Festival and 2004 International Film Festival Rotterdam.

Viewers who have watched Hong Ki-seon's The Road Taken (2003), Jang Sun-woo's Passage to Buddha (1993), or Park Kwang-su's Chilsu and Mansu (1988) will have seen references to Korea's long-term prisoners of conscience. Jailed for their Communist beliefs, and refusing to renounce their ideology despite torture and intimidation, many of these men spent decades (up to 45 years) in South Korean prisons. Only in the 1990s, with pressure applied from Amnesty International and against the backdrop of democratic reforms, did large numbers of unconverted prisoners gain their freedom.

The films mentioned above, to no surprise, are primarily concerned with the time that the prisoners of conscience spent in jail. However Repatriation begins as the men are released from prison, focusing on their efforts to adapt to South Korean society and their campaign to be repatriated to North Korea. By starting his documentary at a time when most news agencies were switching off their cameras, director Kim Dong-won gives us a rare insight into the complete story of these men and how their lives have been shaped by their convictions.

The films mentioned above, to no surprise, are primarily concerned with the time that the prisoners of conscience spent in jail. However Repatriation begins as the men are released from prison, focusing on their efforts to adapt to South Korean society and their campaign to be repatriated to North Korea. By starting his documentary at a time when most news agencies were switching off their cameras, director Kim Dong-won gives us a rare insight into the complete story of these men and how their lives have been shaped by their convictions.

Repatriation is anything but a dispassionate, neutrally-observed recording of events (if it's even possible to make such a documentary). After getting over the initial awkwardness of their encounters, Kim starts to develop a close friendship with several of the ex-prisoners, particularly a man named Cho Chang-son who served 30 years after being captured as a spy. Although ideology sometimes leads to friction between the two, Cho and Kim come to trust each other, each one learning a great deal from the other's experience. As they take part in a movement to campaign for repatriation, the police start to crack down and the director is even arrested on charges of violating Korea's draconian National Security Law.

Throughout this and the events to follow, Kim's soft-spoken but forthright narration serves as an anchor for all that the documentary shows us. By describing his own feelings and his personal involvement in the events that we see, we are given a more complete and honest portrait of the men and their lives, making the dramatic events of the film particularly moving.

Director Kim Dong-won is one of Korea's top documentary filmmakers, and a hugely influential figure in the independent film sector. Kim's Sanggye-dong Olympics is seen as a key early milestone in the independent documentary movement in Korea. With Repatriation, a project that took him many years and much effort to produce, he won over an unusual amount of attention from local media and critics. After debuting at the 2003 Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival in Japan, the film won the Freedom of Expression award at Sundance in the US. When it was released in Korea in March 2004, it became the best-selling local documentary ever.

Repatriation is equally effective in portraying the experiences of some noteworthy participants in history, and giving insight into the situation faced by Korea as an ideologically divided nation. From Kim's recollections of watching anti-communist films as a kid to his heartbreaking interviews with prisoners who did convert under the pain of torture, this film has opened many eyes and challenged many preconceptions. For anyone seeking clarity about the complex and largely misunderstood relations between South and North Koreans, Repatriation is essential viewing. (Darcy Paquet)

Repatriation ("Songhwan"). 148 min., mini DV, color. Directed and narrated by Kim Dong-won. Produced by PURN Productions. Cinematography by Kim Dong-won, Kim Tae-il, Jung Chang-young, Jang Young-il, Byun Young-ju, Moon Jung-hyun, and Kong Eun-ju. Edited by Kim Dong-won. International sales by Indiestory. Winner of the Freedom of Expression Award at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival. Released in Korea on March 19, 2004. Seoul admissions: 19,202. Nationwide admissions: 23,159.

A documentary on roadkill? Such an obscure, dare I be ironic and say pristine, topic was a must-see for me during one of my trips to the Busan International Film Festival. I assumed this was the first documentary ever on roadkill. Yet when I got a chance to talk to One Day on the Road director Hwang Yun after the screening, she informed me she was aware of at least one other screened at festivals. With the topic still a rare one explored, the general theme Hwang sifts from this road refuse is not. Hwang shows us how the carcasses on the side of the road are signs of the trade-offs we make for 'progress.'

The documentary follows the work of ecologist Taeyoung and his team as they study roadkill through research funded by the South Korean Ministry of Environment. Cars, trucks, buses rush past Taeyoung and his crew, giving the viewer an eerie premonition of the deathly results we will see of various species. With each marking on the road and ledger, the animal death toll builds up on screen. We are introduced to the network of carnage, how dead insects attract birds whose hunger leads them to their own death on the road, what is termed "secondary roadkill". We hear of other temptations, such as how heat absorbing asphalt encourages reptiles to lie down on them for easy smooshing. We witness the physics of how the wind from speeding cars can pull animals into the flow of deadly traffic. And we eventually learn that where there are roads, there are roadkill. This is regardless of conditions. Clear vistas result in roadkill just as obscure vistas do. Although slower speeds might help bird species, amphibians and reptiles will still find death at any speed.

The documentary follows the work of ecologist Taeyoung and his team as they study roadkill through research funded by the South Korean Ministry of Environment. Cars, trucks, buses rush past Taeyoung and his crew, giving the viewer an eerie premonition of the deathly results we will see of various species. With each marking on the road and ledger, the animal death toll builds up on screen. We are introduced to the network of carnage, how dead insects attract birds whose hunger leads them to their own death on the road, what is termed "secondary roadkill". We hear of other temptations, such as how heat absorbing asphalt encourages reptiles to lie down on them for easy smooshing. We witness the physics of how the wind from speeding cars can pull animals into the flow of deadly traffic. And we eventually learn that where there are roads, there are roadkill. This is regardless of conditions. Clear vistas result in roadkill just as obscure vistas do. Although slower speeds might help bird species, amphibians and reptiles will still find death at any speed.

Hwang clearly has compassion for all animal species. You can tell she does not consider insects insignificant casualties and Hwang has sympathy for snakes. Still, during my recent viewing of the DVD, I found Hwang's tactic of anthopomorphizing the animals while simultaneously 'zoomorphizing' cars in her 'Road Rules' segment to be distancing rather than establishing greater connection with the animals which appears to be the intent. The documentary genre may allow for greater telling, but the old adage of showing instead could have been more helpful here.

In laying out the problems animals run into on roads, such as fences and trenches making escape difficult, I found myself thinking about the ingenious animals who have been able to use roads to their advantage. Consider the popular YouTube video of crows in Japan figuring out how to use the hardness of the road to crack nuts they've dropped from wires, then waiting for the lights to signal pedestrian crossing, making it safe for a crow to swoop down to eat the nuts. (Kristine Samuelson & John Haptas' Tokyo Waka about Japanese crows and their relationship to Tokyo is a good primer on the genius in these creatures.) But as is mentioned in the Hwang's documentary, most species cannot adapt fast enough to meet the challenges humans placed between their habitats. Guardrails may keep drivers safe but they also keep many animals trapped on these deadly roads. The roads can turn habitats into islands, separated by a vast ocean of asphalt. Why'd the leopard cat cross the road? Because she can't sleep, mate, and hunt in the same habitat.

I returned to this documentary because Hwang's latest, An Omnivorous Family's Dilemma was screening at the San Francisco Green Film Festival in 2015. Since I watched this documentary for the first time, I have come around to the benefits of living without a car and being critical of car-first urban planning. I now see how focusing transportation initiatives on the unobstructed rapid movement of cars dehumanizes our cities, making it more dangerous for folks traveling at more human speeds to traverse them. The heavily, publicly subsidized storage of private vehicles, otherwise known as side street parking, makes a city an unpleasant place to live. It is frustrating to have to wait forever at stoplights across long uninteresting blocks of nothingness in order to access the shopping strip or mall. So much space is set aside for parking and the streets you must cross often feel more like freeways. By designing cities around cars, you make it more dangerous to step outside of vehicles. Hwang's documentary demonstrates that with roads comes roadkill. But it's not just our four-legged or feathered or slithering or buzzing friends. People die too.

South Korea had the second highest traffic fatality rate and the highest for children for any OECD country in 2014. (My country, the US, is not much better, coming in right behind South Korea.) In an article entitled "Road Safety in Korea" (23rd May 2013) on Nikola Medimorec's wonderful website focused on South Korean urban infrastructure called Kojects, Medimorec found that the most vulnerable group of people from traffic collisions are pedestrians. This horrible road record came to greater attention in a video (posted on May 27, 2015) by the popular Canadian couple Simon and Martina of Eat Your Kimchi after a dear friend of theirs was struck by a drunk-driver. For South Korean cinephiles, we remember the horrible news on the 19th of February 2013 when director Park Chul-soo (301/302 & Green Chair) was struck on the sidewalk, also by a drunk-driver. (Drunk driving is a culprit, and Simon details in that video how South Korean laws regarding drunk-driving exacerbate the problem, but those who study traffic fatalities also argue for reducing speed limits in city streets down to 30 kmh where drivers colliding with pedestrians can do less damage.) These are two personal tragedies that are a small sample of many more human deaths on our roads. Considering the human toll, we might wonder from watching Hwang's One Day on the Road, are the kestrels on the road the canaries in the coalmine warning us of the car carnage that comes with the auto dependency public policy has wrought? (Adam Hartzell)

One Day on the Road (Eoneunal geu gil-eseo). 97 min., color. Directed by Hwang Yun. Produced by Studio DUMA. Distributed by Jinjin Pictures. Screened at 2006 Jeongdongjin Independent Film Festival, 2006 Green Film Festival in Seoul, 2006 Busan International Film Festival, 2006 Seoul Independent DOcumentary Film & Video Festival, 2006 Seoul Independent Film Festival. Released in Korea on March 7, 2008. Seoul admissions: 2,884. Nationwide admissions: 3,380.

Our School may not seem at first glance to be a particularly eye-catching documentary. Centered on a K-12 school for Korean students in Hokkaido, Japan, the film contains few dramatic twists and for the most part just observes the students at school interacting with each other and expressing their thoughts. Nonetheless the film achieved remarkable popular success within the realm of independent cinema, attracting more than 70,000 viewers over four months, partly by promoting community screenings in provincial cities throughout Korea. At the time of this writing it is the most succussful Korean documentary of all time.

What made this film so popular? South Koreans will obviously view it differently from people of other nationalities, in that it touches so much on issues of Korean identity. Set in a country where discrimination against Koreans exists on both a personal and an institutional level, the film shows how Korean culture and language serve to create a unique, close-knit community for these strikingly idealistic kids. As one student puts it, "It's a different matter to maintain your national identity in South Korea, your homeland, compared to Japan. In South Korea, you can keep it passively, you don't need to exhibit it, but for Korean residents in Japan, if you don't demonstrate it, it will fade away."

What made this film so popular? South Koreans will obviously view it differently from people of other nationalities, in that it touches so much on issues of Korean identity. Set in a country where discrimination against Koreans exists on both a personal and an institutional level, the film shows how Korean culture and language serve to create a unique, close-knit community for these strikingly idealistic kids. As one student puts it, "It's a different matter to maintain your national identity in South Korea, your homeland, compared to Japan. In South Korea, you can keep it passively, you don't need to exhibit it, but for Korean residents in Japan, if you don't demonstrate it, it will fade away."

There is also the issue of language. Non-Koreans watching this film will in one sense be experiencing it in black-and-white, in not being able to hear the distinctive Korean dialect that is a product of the students' upbringing. In this and other respects, I imagine that Korean viewers find in this film a fascinating mixture of the familiar and the unfamiliar.

Director Kim Myung-jun narrates Our School with simple, straightforward observations, and as viewers we can sense the personal warmth he feels for the students. However he is somewhat coy, at least initially, in presenting the political dimensions to his story. Only after a thorough introduction to the school, the teachers, the students, and various school programs does he mention that the school was founded with support from North Korea. Most of the students also seem to feel a stronger bond with the North than the South, though they are in no way hostile to the latter. Later on, the oldest students in the school take a trip to the North, which they find tremendously inspiring, even as it further alienates them in Japan, where anti-North Korean feeling is rising.

Perhaps the most surpising aspect of this documentary is the sincerity, values and passion that you find in the words of these teenagers. They represent perhaps a unusual case of being schooled in socialist ideals while growing up within a capitalist system. The contrast with teenagers from contemporary South Korea could not be more striking.

Yet in many ways the students' lifestyle is in danger of disappearing. The school faces declining enrollment, both due to the shrinking population of Hokkaido and to the fact that many parents are nervous about depriving their children of an education in Japanese schools. Institutional discrimination doesn't help: the government has designated it a vocational school, making it more difficult for the students to attend university. Parents had to fight even to get the street in front of the building declared a school zone.

In some ways director Kim avoids asking the hard questions in this documentary. Issued related to North Korea, for example, or the even more blasphemous question: would it really matter if these students were to lose their Korean identity, and fully assimilate into Japanese society? Though I suppose to a certain extent these questions can be found within the documentary itself, in the students' passion and the conviction of their beliefs.

For me personally, Our School was intriguing, but not nearly as involving and thought-provoking as Kim Dong-won's Repatriation, to name another local documentary that became a theatrical hit. I also found myself being more drawn in by another recent documentary that examined the relationship between Japan and Korea: Kim Deok-cheol's People Crossing the River (despite that film's structural faults). Maybe it was Our School's fascination with Korean collective identity that left me, as a non-Korean, feeling left on the outside. Nonetheless, I learned a lot over the film's 131 minute running time, and anyone with a special interest in this area will find it a worthwhile viewing. (Darcy Paquet)

Our School ("Uri-hakkyo"). 131 min., DV, color. Directed and narrated by Kim Myeong-jun. Produced by Studio Nurinbo. Edited by Kim Myeong-jun and Park So-hyun. Distributed by Jinjin Pictures. Co-winner of Woonpa Fund Award for Best Documentary at 2006 Pusan International Film Festival. Released in Korea on March 29, 2007. Seoul admissions: 19,202. Seoul admissions: 32,154. Nationwide admissions: 55,815 (70,000+ including group screenings).

![]() Out: Smashing Homophobia Project (2007)

Out: Smashing Homophobia Project (2007)

Korean media outlets have perfected the art of concealment. On TV, identities are doubly disguised with mosaics blurring faces into pixelated squares and voices cranked through digital modifiers to resemble a helium addict's vocal range. Suspected criminals, unwed mothers, even infants put up for adoption all have their identities masked. But in July 2005, a MBC news program chose to air untouched hidden camera footage of lesbian bars -- effectively outing anyone who wandered past the camera lens.

The Feminist Video Activism WOM collective, in their documentary triptych Out: Smashing Homophobia, succeeds in protecting each girl's identity while ushering the audience into the triple lives of Korean lesbian teenagers.

Filmed as three separate self-documentaries by Chunjae, Choi, and Koma -- with on-screen and off-screen editing intervention by Lee Young, a WOM member -- Out invents ways to reveal self without having to reveal faces. Having eschewed digital mosaics or voice masking, each adolescent concocts her own tray of tricks. One student trains the camera on puppy shaped slippers while she talks. Silhouettes against a freeway, a pair of feet, an empty classroom, all are synedoches for self. The girls become their voices and what their camera sees. Slim slices of physicality are allowed to slip in as well -- a firmly curved mouth or a baby fat cheek.

Filmed as three separate self-documentaries by Chunjae, Choi, and Koma -- with on-screen and off-screen editing intervention by Lee Young, a WOM member -- Out invents ways to reveal self without having to reveal faces. Having eschewed digital mosaics or voice masking, each adolescent concocts her own tray of tricks. One student trains the camera on puppy shaped slippers while she talks. Silhouettes against a freeway, a pair of feet, an empty classroom, all are synedoches for self. The girls become their voices and what their camera sees. Slim slices of physicality are allowed to slip in as well -- a firmly curved mouth or a baby fat cheek.

Out succeeds in capturing their individuality. These are no anonymous computer-masked personas. Chunjae jokes about her girl-chasing bravado in Out's most hilarious sequence. A blank white circle and a series of yellow post-it notes, with squiggles to denote arched eyebrows or pursed lips, becomes an anime-generation girl's way of expressing her crush on a fellow bus rider. By choosing not to disguise voices, the filmmakers let us hear Choi's giggling coyness, Koma's calmness. The risk of exposure is there, the girls admit in a Q&A session at the 9th Women's Film Festival in Seoul, but "we trust you the audience. We wanted you to get to know us."

"The biggest change is that I went to high school. Not that I started dating a boy." If all three parts focus on teenagers, isn't there a danger of repetitive angst? How much could someone who has yet to grow into her feet have to say about identity and the politics of sexuality? But WOM has pruned each girl's tale to a clear narrative arc -- an inconvenient boyfriend in the first episode, "Coming Out," profound emotional ambivalence in "Outing" and family tensions in "Outsider."

Chunjae, like many queer people, finds her attraction inconveniently opposed to her identity. After a nerve-wracking middle school experience where even the most well-meaning counselors would insist she was just going through a phase, Chunjae isn't about to relinquish her lesbianness. No matter how much her patronizing boyfriend tries to insist that her love for girls is something in the past, her film gaze lavishes attention on all the mini-skirted girls.

In "Outing," Choi flounders with her feelings and sexuality, often with filmmaker Lee Young on screen as a navigator. "I'm an ordinary girl" Choi insists, "unless you think that me dropping out of school makes me special." And her shots depict just that, a 19 year old girl who does the dishes, plays with her cat, and goes to 2006 World Cup gathering with her new love interest, who just happens to be a girl. Her one-sided crushes on girls prods her to question if all she really wants is their friendship. Her process of (even if those safe and sound in their identities might groan with the familiarity of her agony) dropping the "maybe" from her sexual identity is a triumph that the audience cheers.

In any coming out story, the family reaction is often the site of maximum drama. But what if you can't come out to your parents? Though Koma's little sisters have read her diaries, threaten to out her to their parents, and even refuse to share utensils or water with her, she emerges from the three narratives as the unshakeable one. On camera, she celebrates her first year as the Korean Lesbian Counseling Center's youngest activist, and relishes her first Queer Pride Parade. But her yearning for reconnection to her family and an unreachable honesty with her friends is heart-wrenchingly raw, despite her measured poise. Alone in her room, underneath a blanket with only a flashlight Koma finally confesses, "But then again, Mother, you already knew, didn't you? Even before me..."

The footage of the defiantly joyous if rain spattered Queer Pride parade summarizes how far the queer community has already advanced. Yes. An entire subculture in San Francisco is condensed in the Korean case into one lone leather daddy and one drag queen striding down the street, but there is a public community, one with filmmakers and teenage activists and confused 19 year olds. Koma's stash of rainbow pins might be squirreled away, but she flies her six-color rainbow cellphone charm as her one public freedom.

Out opens with all three protagonists rapping in a recording studio, their faces hidden behind carnival style half-masks. The film ends with the three in the same masks, posing atop a roof in Seoul for what will become the promotional poster. Hidden faces, but raised voices, each girl leans forward to tell her own story. (Annie Koh)

Out: Smashing Homophobia Project ("Out: Iban-geomyeol du beonjjae iyagi"). 110 min., DV, color. Produced, edited, shot and directed by Feminist Video Activism WOM. International sales by Sapo. Winner of the Documentary Ock Rang Award at the 2007 Women's International Film Festival in Seoul. Website: www.out.or.kr

For those who hate when people talk during a film screening, I have a solution. Let's all promote teaching our region's tactile signing in schools. This way, everyone will know their region's tactile language and can comment to their seatmates through touch, not voice. Tactile signing has many such advantages, as does a region's sign language. So, while we're at it, let's promote the teaching of a region's sign language in all schools too. As the American Sign Language promoting non-profit Language First puts it, sign languages are "language insurance". If you ever lose your voice or are in a situation where a vocal language is disadvantaged, you would have a sign language and a tactile language as a back-up.

But honestly, all I've said above are secondary reasons for learning sign and tactile languages. The main reason is for access to services and each other for our fellow folks who are Deaf or DeafBlind. (The difference between 'd' and 'D' is often used in English to denote whether someone is hard of hearing versus someone who is hard of hearing and identifies with the Deaf community. Similarly the spelling 'DeafBlind' can be used to denote a distinct culture for those who identify with that community and the Protactle movement.) Knowing these languages allows more citizens to communicate with each other. So beyond the utility to the hearing and sighted individual, teaching these languages in our school systems is the right thing to do in any fully-functioning democracy.

But honestly, all I've said above are secondary reasons for learning sign and tactile languages. The main reason is for access to services and each other for our fellow folks who are Deaf or DeafBlind. (The difference between 'd' and 'D' is often used in English to denote whether someone is hard of hearing versus someone who is hard of hearing and identifies with the Deaf community. Similarly the spelling 'DeafBlind' can be used to denote a distinct culture for those who identify with that community and the Protactle movement.) Knowing these languages allows more citizens to communicate with each other. So beyond the utility to the hearing and sighted individual, teaching these languages in our school systems is the right thing to do in any fully-functioning democracy.

Korean tactile signing is on full display in my favorite South Korean documentary of all time, Yi Seung-jun's Planet of Snail. Beyond the language's utility, there is a tremendous intimacy on display as well since the language is mediated through touch. As the subhead of Andrew O'Hehir's review of the documentary in Salon states, the story of the marriage between Young-chan and Soon-ho "is the movie romance of the year". Part of how this romance is shown and not told is through all the touching and what that touching communicates.

Eventually in the review of any documentary about disability, the disabilities on screen are explained to you. It is clear that Young-chan is both Deaf and Blind. (Yet where he falls on the spectrum of what he can and can't see and hear is not clear.) Soon-ho's disability is that of having an unorthodox body. In her case, I'm not going to explain her disability more than that. Too often, non-disabled folk expect to have disabled bodies explained to them. Someone's impairments might be explained during casual conversation on the disabled person's terms. But non-disabled folk often feel entitled to explanations. The problem is, this question of 'What is wrong with you?', (this is how it is often heard even if not spoken explicitly), can strike disabled folks just like the question 'Where are you from?' can sound to Asian and Latinx Americans. The question excludes rather than includes; the question others.

Young-chan and Soon-ho are married. They are clearly in love and it is this love that seeps throughout the film and touches the viewer through the light reflected on the screen. They are truly an enjoyable couple to watch. We witness them go about their day as a couple watched by Yi's camera. We see them do things as mundane as install a new ceiling light. We hear them hanging out with friends. We watch as Young-chan takes his Hebrew. We are casually shown the technologies that allow them accessibility, that afford greater activity in their wider community.

To Yi's credit, we are not encouraged to see these prosaic everyday activities as "inspiration porn". Coined by the late, (and awesome), Australian disability activist and comedian Stella Young, "inspiration porn" is the use of disabled folks accomplishing daily tasks as 'inspirational' for non-disabled folks to 'stop being lazy'. Regardless of one's intention, when folks post or retweet or like videos of, say, deaf children responding to amplified noise after receiving a cochlear implant, they are using the disabled person as a disembodied metaphor, not as a full human being whose wider context is lost in the posts that many keep liking. What Yi's documentary provides is greater context that is often missing from our viral videos. And as David Scott Different notes, this same "subject-hood and agency" (p 268) is missing from South Korean genre film where they "resort to familiar tropes of the disabled figure" that strip them of their humanity (p 268). ("Always, Blind, and Silenced: Disability Discourses in Contemporary South Korean Cinema" in Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies Volume 11, Issue 3, 2017 published by Liverpool University Press.) And by rarely casting disabled actors and actresses in disabled roles, (one of the few instances of actually casting someone disabled I can think of is Kim Hui-ra, a stroke survivor playing a stroke survivor in Lee Chang-dong's film Poetry), such tropes are likely to continue. The importance of is Yi's documentary is that he maintains the humanity of the subjects throughout. They are always active subjects.

My concern as a non-DeafBlind person emphasizing the intimacy of tactile signing earlier is that I am making it out to be something exotic. This is partly why I read a great deal by disabled writers to keep my ableism in check. The particular form of ableism exhibited towards DeafBlind folks has been named 'Distantism' by DeafBlind writer John Lee Clark. One can communicate via speech or sign from a certain distance. As a result, the sighted or hearing often privilege a certain distance when communicating. Until the body suits we witness in films such as Ready Player One (Steven Spielbreg, USA, 2018) become a reality, DeafBlind folk need to be close to communicate. In an excellent post entitled "Distantism" on his Tumblr blog, Clark explains how education in the DeafBlind community, unlike in the separate Deaf or Blind communities, has been controlled by non-DeafBlind individuals. As a result, whenever DeafBlind students might cluster closely to communicate, they have been separated, assigned a non-DeafBlind interpreter as the only person they may embrace. The closeness of tactile signing makes the non-DeafBlind person uncomfortable so they must "... destroy moments when we cluster and go tactile." Clark even goes so far as to consider his choice of cane so it is the least obstructive and allows him to get close at a moment's notice. He doesn't want people "... parting like the Red Sea before our rod" and has "... worked on making my bubble as thin as possible, ready to pop the instant there's an opportunity for connection."

It's that word "connection" that Clark uses that might be better than my word, "intimacy". I can argue that it's the same thing, but I look forward to reading more of Clark's, and other DeafBlind folks', writing to see if my description here is correct or representative of what I'm missing or misunderstanding. And I hope to read essays from DeafBlind folk in South Korea so I can avoid, as disability scholar Eunjung Kim writes in her book Curative Violence: Rehabilitating Disability, Gender, And Sexuality in Modern Korea (Duke University Press, 2017), "assuming the universal characteristics of disability insofar as everyone with a disability is believed to go through the same experiences wherever they are located" (230).

As I noted above, distantism and audism (Hearing prejudice towards Deaf folk) could be partially addressed if we all grew up in school systems that taught the region's sign and tactile language. Planet of Snail is a reminder that all accessibility measures allow us to communicate with each other further. And most importantly, accessibility allows us to love.

In fact, "Access Is Love", as American disability activists Sandy Ho, Mia Mingus, and Alice Wong have framed it through the organization DisVisibility. (Full disclosure: Alice Wong is a friend of mine.) Or more specifically, they write - "Access Is Love aims to help build a world where accessibility is understood as an act of love, instead of a burden or an after-thought." DisVisibility demonstrates accessibility as an act of love and Planet of Snail reminds us that access to language enables love. Planet of Snail reminds us that language can come in forms other than spoken and written. It can come through tender taps and caresses that communicate more than you may have ever dreamed of. If Yoon-chan and Soon-ho weren't given access to tactile language, they may not have become the beautiful couple in love we witness on screen. And our world would be lesser without them and this beautiful film. (Adam Hartzell)

Planet of Snail ("Dalpaeng-yi-eui byeol"). 85 min., color. Shot and directed by Yi Seung-jun. Produced by CreativeEAST and Dalpaengee. Distributed by Zoa Films. Winner of the IDFA Award for Best Feature Length Documentary at the 2011 International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam.

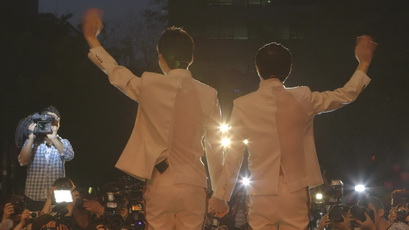

One day while I was pedaling home from work along Market Street in San Francisco, I saw two men of Asian descent in brightly colored clothes walking hand in hand. They had lanyards for some event draping from their necks. They were walking across to my right as I pedaled through the same intersection they were crossing. It was one of those moments when the recognition wasn't fast enough, in fact, I was much further along The Wiggle, (the name for the route of lowest grade going from East to West in San Francisco), when I finally realized who those two men most likely were. Putting the lanyards around their necks together with the events happening at that time, I realized it was probably South Korean director Kim Jho Gwang-soo and his partner Dave Kim who were in town for the Frameline (LGBT) Film Festival where director Kim's film Two Weddings and a Funeral was screening. As much as one can be when rushing with endorphins while pedaling home, I was deflated that I might have missed my one chance to talk w/ director Kim about one of my favorite South Korean films, one he produced, Wanee & Junah.

But thanks to CAAMFest, the Asian American film (and food and music) festival in San Francisco, I might get a second chance, because the Kims will be in town for screenings of Jang Hee-sun's documentary about their public wedding in Seoul, My Fair Wedding. Gay marriage which sanctions all the rights of straight marriage is still not established in South Korea. It's 'legal'. You can do it. You can be gay and have a partner to whom you are committed, but none of the legal rights permitted state-sanctioned husband and wives are accessible for Queer South Koreans. And most Queer South Koreans remain closeted because of the harsh social and economic discrimination they would receive if they were publicly out.

But thanks to CAAMFest, the Asian American film (and food and music) festival in San Francisco, I might get a second chance, because the Kims will be in town for screenings of Jang Hee-sun's documentary about their public wedding in Seoul, My Fair Wedding. Gay marriage which sanctions all the rights of straight marriage is still not established in South Korea. It's 'legal'. You can do it. You can be gay and have a partner to whom you are committed, but none of the legal rights permitted state-sanctioned husband and wives are accessible for Queer South Koreans. And most Queer South Koreans remain closeted because of the harsh social and economic discrimination they would receive if they were publicly out.

It is this conservative milieu that Jho Gwang-soo & Dave, both involved in the film industry, decided to put on a production for their wedding after being together for over 9 years. The event is an opportunity for them to profess their love and to advocate for eventual greater freedoms for Queer South Koreans, including marriage.

If you don't know the Korean language well, the film is really one you need to watch a few times, or when it comes out on DVD, have your remote handy, because there is a lot of text on screen and the subtitles are quick and plentiful. Even with pausing the frame on my screener, I still feel I missed a great deal. But one thing this film did have me thinking is how little I know about South Korea's legal framework. For example, can South Korea's provinces implement laws different from each other such has happened with same-sex marriage in the USA. Can Gangwon allow for same-sex marriage while South Jeolla allows for civil unions? And then there are the legal issues that likely resulted in the blurring of the faces of some of the anti-gay protesters. I mean, they were there protesting in public, so why couldn't director Jang show their faces in the documentary? As with every South Korean film I watch, especially documentaries, I still have a lot of background research to do.

My Fair Wedding does not seek to educate me on those aspect of South Korea's legal system. (These are definitely questions I will ask the Kims if I am able to interview them at CAAMFest). What it seeks to do is show us the build-up to Dave and Jho Gwang-soo's wedding, the stress that all weddings bring, but with the addition of the politics that men who fall in love with women (and vice-versa) have the privilege of ignoring. Dave and Jho Gwang-soo reveal some frustrating moments that are both personal and political. Yet not in spite of these tensions, but because of their devotion as a couple to work through these tensions, they do reach the day they've been waiting for.

Along with My Fair Wedding reminding me how much I have to learn about administrative aspects of the South Korean government and the country's laws, I am also reminded of how the path taken to achieve Gay Rights in New Zealand, Canada, the US and other Western countries is not necessarily the path that should be taken in South Korea. As much as international support is needed, the gains will never stick unless the Gay Rights movement in South Korea is autochthonous, My Fair Wedding is a wonderful document on that self-paved road towards greater possibilities for Queer South Koreans. It tells of the struggles while taking moments to relish in the beauty of testifying to ones love and offering witness and support to a friend or family member's testimony of their love. I was brought to tears when Jho Gwang-soo's mother announces her support for her son's relationship and all Queer folk in South Korea. That is the moment where all the stress of the event subsides for me, the moment of My Fair Wedding that will stay with me for some time. That and how absolutely gorgeous Dave looks in that wedding dress during the one photo shoot. (Adam Hartzell)

My Fair Wedding (Mai pe-o weo-ding). 94 min., color. Directed by Jang Hee-sun. Produced by Rainbow Factory. Distributed by Jinjin Pictures. Screened at 2014 Busan International Film Festival, 2014 Seoul Independent Film Festival and CAAMFest 2015.

![]() An Omnivorous Family's Dilemma (2014)

An Omnivorous Family's Dilemma (2014)

I had met briefly with director Hwang Yun years ago at a screening of One Day on the Road, a compelling documentary about, of all things, roadkill. Before I watched An Omnivorous Family's Dilemma in preparation for its screening at the 2015 San Francisco Green Film Festival where Hwang will be in virtual attendance via Skype, I wasn't aware this documentary was made by her. I was delighted to find out Hwang is still making documentaries that stimulate profound contemplation.

With three documentaries focusing on our relationships with animals, (her first is a documentary about a tiger referenced in the beginning of this documentary), I think it is now fair to say that Hwang's muse is other species. And she gets up close to these personable animals. She challenges herself to consider the impact her life has on the lives of animals in South Korea. Though her second documentary didn't lead her to sell her car, (it is in that documentary where Hwang discovers that where there are roads, there are roadkill), this documentary led her to choose vegetarianism, and to choose the same for her young son. (Her husband is a tad less game.) The film follows her confrontation with the realities of factory farming and the difficulty of being vegetarian in South Korea.

With three documentaries focusing on our relationships with animals, (her first is a documentary about a tiger referenced in the beginning of this documentary), I think it is now fair to say that Hwang's muse is other species. And she gets up close to these personable animals. She challenges herself to consider the impact her life has on the lives of animals in South Korea. Though her second documentary didn't lead her to sell her car, (it is in that documentary where Hwang discovers that where there are roads, there are roadkill), this documentary led her to choose vegetarianism, and to choose the same for her young son. (Her husband is a tad less game.) The film follows her confrontation with the realities of factory farming and the difficulty of being vegetarian in South Korea.

Hwang began to think more about food when she became responsible for providing sustenance for someone else, her son. One of her son's favorite foods is pork cutlet. This sent Hwang to research how the food got to her son's plate. The fact that pigs were being culled at this time in South Korea due to a hoof and mouth outbreak added to the concern. She sought out factory farms to learn about their practices, but it took her awhile before such a farm let her on site to film.

The film's title-sake is obviously Michael Pollan's An Omnivore's Dilemma. Hwang meets her own Joel Salatin from that book in the form of Mr. Wu, a farmer who has his pigs roam freer and does not inject them with chemicals to enhance growth and speed up births. On his farm, Mr. Wu lets Hwang get physically and emotionally close to a specific sow and her recent litter. It is this alternative farm where a more 'ethical' approach to meat production seems possible. But there is a powerful image later in the film in which Hwang leaves it to the audience to consider whether Mr. Wu's farm truly offers an alternative.

Telling through images represents part of what I appreciate about Hwang's film, making an often force fed topic feel less didactic. Another similar moment allows the audience to make a connection with factory farm practices and feminist concerns. Referring to the sows constrained in their cages, the farmer says 'It's a pity they were born female." We are then shown hens cooped up in a factory so humans can 'cost-effectively' enjoy the protein of their unfertilized labor.