2004 Pusan International Film Festival Report

by Darcy Paquet and Kyu Hyun Kim

Opening Film 2046, dir Wong Kar-Wai

For cinephiles living in Korea, the PIFF has become a fixture on the yearly calendar: both something to look forward to, and an event to mark the passage of time, rather like Christmas. Each year, large numbers of filmmakers, journalists, producers, and other members of the international film community descend on the city to gather together, watch new Asian films and to do film-related work. At the same time, crowds of young Koreans with a surprising passion for world cinema fill the streets and theaters, making for a lively, festive atmosphere. Like any big event, PIFF has its share of problems or annoyances, but in general, both guests and regular attendees seem to hold extraordinarily warm feelings for the festival. Mostly I mark this down to the mood created by Koreans' intellectual curiosity and enthusiasm, one of the most admirable aspects of its culture.

This festival report is a collection of personal experiences and journalistic observances by Darcy and Kyu Hyun during the 9th PIFF, which ran from October 7-15, 2004.

Kyu Hyun Kim: October 7, 2004 / Opening Ceremony

As I was boarding the KTX "bullet" train headed for Pusan, I was full of trepidations. After all, this is the first time I am attending the Pusan International Film Festival (and it is my first visit to Pusan in more than fifteen years). Now in its 9th year, the PIFF promises to pull off its biggest and best-attended pageantry ever. The festival has scheduled 264 films from 63 nations, with its ambitious program encompassing a wide range of available cinematic formats, political viewpoints and commercial accessibility. Quirky and personal short films, political documentaries, experimental animations, abstract and dry artistic statements and out-and-out commercial blockbusters vie for the audience's attention.

It must be stated at the outset that the selection for this year's PIFF choice of Korean films was somewhat disappointing, for the simple, selfish reason that some of my personal wishes were not fulfilled. The Cannes winner Old Boy and the Venice winner 3-Iron lead the pack of thirteen films in the "Korean Panorama" section, half of which are already available as DVDs as of October 2004, with the yet-to-be-released films So Cute, This Charming Girl, and My Generation (pictured left) assigned to "New Currents" section. Shin Sung-il Is Missing is the sole Korean entry among "Critic's Choice" selections, while the popular Repatriation and A State of Mind, a fresh look at North Korea, are just two among the robustly represented documentaries. The Closing Film is Han Suk-kyu's new thriller The Scarlet Letter. MIA are the films from late Summer and Fall seasons that I had hoped would make the list: Spider Forest, Hypnotized, Doll Master, To Catch a Virgin Ghost, The Family, S Diaries and of course Some. But no matter, what is available is already more than I could properly cover even if I run around like an Energizer Bunny without sleep and skipping lunch. And of course there are 230-plus non-Korean films, an impressive chunk of which are world premieres, especially the latest works from renowned Japanese, Chinese and Hong Kong directors.

It must be stated at the outset that the selection for this year's PIFF choice of Korean films was somewhat disappointing, for the simple, selfish reason that some of my personal wishes were not fulfilled. The Cannes winner Old Boy and the Venice winner 3-Iron lead the pack of thirteen films in the "Korean Panorama" section, half of which are already available as DVDs as of October 2004, with the yet-to-be-released films So Cute, This Charming Girl, and My Generation (pictured left) assigned to "New Currents" section. Shin Sung-il Is Missing is the sole Korean entry among "Critic's Choice" selections, while the popular Repatriation and A State of Mind, a fresh look at North Korea, are just two among the robustly represented documentaries. The Closing Film is Han Suk-kyu's new thriller The Scarlet Letter. MIA are the films from late Summer and Fall seasons that I had hoped would make the list: Spider Forest, Hypnotized, Doll Master, To Catch a Virgin Ghost, The Family, S Diaries and of course Some. But no matter, what is available is already more than I could properly cover even if I run around like an Energizer Bunny without sleep and skipping lunch. And of course there are 230-plus non-Korean films, an impressive chunk of which are world premieres, especially the latest works from renowned Japanese, Chinese and Hong Kong directors.

Trying to calm down my accelerating heartbeat, I braced myself for the hectic running-back-and-forth among the PIFF headquarters and various locations for big events, as well as competitive taxicab rides between Haeundae, the beachfront resort town where most hotels are located, and Nampo-dong, the site of the movie theaters other than SfunZ (read s-fun-zeeh) Megabox (No, it's not a heavy-metal cyborg cousin of Sponge Bob, it's a medium-sized mall coupled with a good-sized multiplex literally overflowing with young film fans at this moment). Likewise, I resolved myself not to mind even when I get pushed aside, trampled, my shins kicked, or otherwise manhandled by the milling crowd of thousands. After all, this is the biggest film festival in East Asia, drawing journalists, filmmakers, buyers and distributors and serious film fans from all over the world. I had carefully picked out 27 films (with about a dozen backup choices) to be covered in a week's time, but of course I knew that this list would have all the practical utility of the label on a bag of potato chips claiming they are free of animal fat.

As the train moved into the Pusan Station, leaving me barely enough time to go through the Guest List, however, all these anxieties recede and the uncontrollable surge of euphoria began to take over. I was finally at the PIFF!

As soon as I arrived in my hotel, I was immediately whisked off by Mr. Editor, Darcy Paquet, to the Opening Ceremony and the screening of the Opening Film, Wong Kar-wai's 2046, at a huge outdoor theater set up in the Yachting Club.

Briskly walking on the red carpet with Mr. Editor, caught somewhere in the procession of the stars and VIP guests and with the puny digital camera hanging uselessly from my neck, it was impossible not to be sucked into the dazzle and glamour of the moment. For one minute or so I had a brief taste of what it is like for the film stars, to stare into hundreds of

faces, eager with desire and adoration, and especially into the cascade of blinding illumination and flashes from camera, little explosions of light that leave orange and green after-images in your eyes.

Briskly walking on the red carpet with Mr. Editor, caught somewhere in the procession of the stars and VIP guests and with the puny digital camera hanging uselessly from my neck, it was impossible not to be sucked into the dazzle and glamour of the moment. For one minute or so I had a brief taste of what it is like for the film stars, to stare into hundreds of

faces, eager with desire and adoration, and especially into the cascade of blinding illumination and flashes from camera, little explosions of light that leave orange and green after-images in your eyes.

Following a nice performance by a band mixing jazz, rock and traditional Korean instrumental music, and the Opening Ceremony m.c'd by the stars Ahn Sung-ki and Lee Young-ae, Wong Kar-wai and Tony Leung gave spirited introductions to their latest film in English, to an enthusiastic response of the audience.

2046 is ostensibly a sequel to Wong's In the Mood for Love, widely hailed as a masterpiece, in that it is the continuation of the story of the journalist-turned-novelist Chow. 2046 is, like its predecessor, beautiful and seductive, and envelops a willing viewer in the opium smoke of romantic haze. It does, however, suffer from editorial problems and feels like a penultimate version rather than a complete product. The entire Gong Li sequence, where she plays a gambler named Black Spider, takes place several beats after the film's emotional climax has been reached. Even though the special effects

were tacky and unconvincing, I felt that the futuristic sequences involving Kimura Takuya and Faye Wong were by far the most effective part of the film. Zhang Zi-yi is also stunning as a vampish "play-girl" with stiletto-like eyelashes, although her character hardly represents a radical departure from her image of an obstinate, strong-willed tart. The concept of androids suffering from the symptoms of delayed emotional response was also intriguing, even if the presentation probably could be accused of lacking in basic science fiction literacy. Alluring and lackadaisical at the same time, 2046 was an appropriate film to start off the Festival, showcasing the glamour and star wattage of the Asian cinema, before the festival turned toward the more emotionally and politically challenging fare in the coming weeks.

People at PIFF: Deborah Gabinetti, Director of Bali Film Commission

A film commission is an organization that assists filmmakers when they shoot on location in another region or country. They may provide help in arranging visas, getting film equipment through customs, finding extras, recommending locations, and many other tasks. All of their services are generally provided for free. Most film commissions are given financial support by local governments, in order to promote their region through film and to bring business to local residents. The Bali Film Commission in Indonesia, headed by Deborah Gabinetti, is a rare case of an entirely self-funded film commission, that has the approval of the Indonesian government, but no financial support. Deborah was at PIFF to take part in the launching of the Asian Film Commissions Network (AFCNet), which is a linking of film commissions throughout Asia that will encourage regional co-operation, professional development, and joint promotion of Asia as a shooting location.

* Can you explain what AFCNet is, and what are its main goals?

It's going to be an association of film commissioners in Asia. We're going to pool our resources to establish a strong organization where an Asian or Western filmmaker could come to our organization and find out information on shooting in the different countries. I think some of the difficulties that people confront in Indonesia, is that they go to a tourism office perhaps, or they go to a travel agent, or someone who has no experience with film, and either they're steered in the wrong direction or they don't get an answer. If they're speaking only English they may get no response whatsoever. So if there's a Korean film trying to come to Indonesia, they could contact the local AFCNet office in Korea to get professional assistance.

It's going to be an association of film commissioners in Asia. We're going to pool our resources to establish a strong organization where an Asian or Western filmmaker could come to our organization and find out information on shooting in the different countries. I think some of the difficulties that people confront in Indonesia, is that they go to a tourism office perhaps, or they go to a travel agent, or someone who has no experience with film, and either they're steered in the wrong direction or they don't get an answer. If they're speaking only English they may get no response whatsoever. So if there's a Korean film trying to come to Indonesia, they could contact the local AFCNet office in Korea to get professional assistance.

* Can you tell me a little bit about your experiences assisting with the shooting of the Korean TV drama Something That Happened in Bali?

There were some difficulties with that. The work ethic is quite a bit different in the two countries. Also the translators the Korean crew hired were from a travel agent, so they really didn't understand anything about film, and the Korean crew spoke very little English. The Indonesian crew is generally quite good with English, but to be honest they ended up eliminating the translator completely, because film is another language in itself.

We had some issues with cultural sensitivities as well, and I'll blame some of that on our office because we were so excited about getting this project that we cut some corners in having everything clear and spelled out in advance. For example, overtime -- I did not understand that they work overtime and then they do not pay for it. I'm hearing now that this is pretty much the way that Korean crews work, but we were not made aware of that. Again, it was communication. Not just the language, but in communicating the way that they wanted things done.

The result, as you know, was fantastic. It was a #1-ranked show on SBS in Korea. But of course, people don't see the issues that may have come up during shooting. That's why I think that ACFNet could be really helpful, because when we had these problems I contacted the Busan Film Commission and asked them to help, and they did. They contacted the local production company, and spoke with them about some of the issues. (Mini-interview conducted by Darcy)

Kyu Hyun Kim: October 8, 2004 / "Emiya! I can't move my leg." "Just die. Die right now."

Arriving at the Press Center in the 3rd floor of the SfunZ mall on exactly 9:00 am, I find myself at the tail end of a long, long line that snakes around the narrow corridor leading to the elevators. The Press members are endowed with the privileges of separate industry screenings as well as four free tickets per day. But few of them are relaxing: the competitions for the tickets are fierce. With the tickets evaporating like drops of water on a lump of hot coal, soon the assigned seats for a few films high on my list are gone. Alas, The University of Laughs looks like a casualty of my foot-dragging. Adding to the competition is the newly enforced rule of absolutely no mid-screening admission. Young film fans are lined up in an even longer line extending to the opposite direction, chatting energetically, checking cell phones for text messages, calling their friends up and frantically shouting the info on ticket availability. The fresh-faced volunteers, clad in white T shirts with the PIFF logo, courteously and patiently answer our questions and direct us to the appropriate authorities.

After standing in queue for nearly one and a half hours, I finally managed

to purchase six tickets, two for today and four for October 9. It remains

to be seen how many of these I will actually get to watch.

At 1:00pm, I take up the elevator to the Megabox multiplex for the Thai thriller The Macabre Case of Prom Pi Ram (pictured left), which I had missed at the San Francisco's 4-Star Cinema this summer. It makes an interesting comparison to Memories of Murder, also about a rape-murder case in a rural town. This particular incident took place in 1977 in a dilapidated Northern Thailand village. Two policemen struggle to crack a brutal rape-murder of a seemingly mentally unstable woman. Naturally, the deeper they delve into the case, the uglier and darker it gets, until the final truth implicates the entire male community of Prom Pi Ram, draped in the miasma of moral corruption and sexual violence. Strongly sympathetic to the plight of Thai women, if not altogether feminist, Prom Pi Ram is a deliberately paced police procedural, beautifully photographed with subtle differentiations in color and tone, and well acted by the principals.

At 1:00pm, I take up the elevator to the Megabox multiplex for the Thai thriller The Macabre Case of Prom Pi Ram (pictured left), which I had missed at the San Francisco's 4-Star Cinema this summer. It makes an interesting comparison to Memories of Murder, also about a rape-murder case in a rural town. This particular incident took place in 1977 in a dilapidated Northern Thailand village. Two policemen struggle to crack a brutal rape-murder of a seemingly mentally unstable woman. Naturally, the deeper they delve into the case, the uglier and darker it gets, until the final truth implicates the entire male community of Prom Pi Ram, draped in the miasma of moral corruption and sexual violence. Strongly sympathetic to the plight of Thai women, if not altogether feminist, Prom Pi Ram is a deliberately paced police procedural, beautifully photographed with subtle differentiations in color and tone, and well acted by the principals.

The director Manop Udomdej greeted the audience in a lively Q & A session after the screening. The mostly local, young viewers fired questions at him, in between awkward giggles and stumbles, surprisingly sharp and thoughtful. One viewer wanted to know if the director inadvertently portrayed the female victim as flaunting her sexuality. Another asked about the difference between the real-life case and the film. Director Udomdej fielded these questions with obvious sincerity and candor, clearly appreciating the opportunity. Unfortunately I could not stay around until the end. I had to catch the industry screening of Blood and Bones, one of the most hotly anticipated films at this year's PIFF.

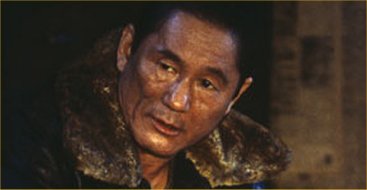

Based on an award-winning novel by the Korean-Japanese writer Yang Seog-il and directed by the veteran Sai Yoichi (Choe Yang-il), Blood and Bones (pictured right) is a brutal, unsparing chronicle of a Korean family surviving against impossible odds in the postwar Osaka. The film is not aesthetically pleasing, nor does it scale the height of stylized realism previously seen, for instance, in Imamura Shohei's Pigs and Battleship. Like an emotional hurricane, it assaults the viewer's sensibilities with scenes of unspeakable emotional and physical violence, especially toward women. Women are raped in this film. Again and again and again and again. They fight back, they rage and curse, they try to commit suicide by eating a whole can of rat poison as if they are crackers, they pray to Buddha for mercy, and then for their husbands' timely and painful deaths: none of these are ultimately effective against the great wheel of violence that keeps the Kim family in an iron grip, germinated and nurtured like maggots over rotten meat by the hellish combination of poverty, greed, ideological struggles and patriarchal beliefs. (There is simply no room in this movie for any dumb nostalgia about the Korean "roots" or the nationalistic mantra about how Japanese are to be blamed for all the Kim family's troubles) When the film has ended, you feel torn between the feeling of hopeless rage and the deep sense of grief and loss that threatens to knock you down.

At the center of this overwhelming experience is "Beat" Kitano Takeshi, playing one of the evilest and most brutal father figures in cinema history. Kim Shunpei, portrayed by Kitano in a full range of adulthood from 30s to the octagenarian old age, is a man literally incapable of expressing any emotion and thought except through violence. In a frighteningly controlled and restrained performance, Kitano gives this rabid jackal of a man three-dimensional depth. It is easy to conceive of a character, who cannot even express love and

pity without an act of destruction, on the pages of a novel, or a screenplay. How many believable portrayals of such men have we really seen in motion pictures? Kitano pulls it off here, his performance every bit as astonishing as Robert DeNiro's in Raging Bull. When Kim, after another round of stormy violence toward his family, suddenly collapses on the floor from a stroke, and in a fit of rage toward his body begins to savagely beat his leg, finally addressing his wife with a croaking plea, "Emiya (Mother of the children)! I can't move my leg," you experience an indescribable combination of emotion. You feel the desire to jump into the frame and kill the bastard with bare hands, and yet you also feel his frustration, his inarticulateness, his inability to ask for forgiveness or understanding, and are forced to confront the tragedy of it all.

At the center of this overwhelming experience is "Beat" Kitano Takeshi, playing one of the evilest and most brutal father figures in cinema history. Kim Shunpei, portrayed by Kitano in a full range of adulthood from 30s to the octagenarian old age, is a man literally incapable of expressing any emotion and thought except through violence. In a frighteningly controlled and restrained performance, Kitano gives this rabid jackal of a man three-dimensional depth. It is easy to conceive of a character, who cannot even express love and

pity without an act of destruction, on the pages of a novel, or a screenplay. How many believable portrayals of such men have we really seen in motion pictures? Kitano pulls it off here, his performance every bit as astonishing as Robert DeNiro's in Raging Bull. When Kim, after another round of stormy violence toward his family, suddenly collapses on the floor from a stroke, and in a fit of rage toward his body begins to savagely beat his leg, finally addressing his wife with a croaking plea, "Emiya (Mother of the children)! I can't move my leg," you experience an indescribable combination of emotion. You feel the desire to jump into the frame and kill the bastard with bare hands, and yet you also feel his frustration, his inarticulateness, his inability to ask for forgiveness or understanding, and are forced to confront the tragedy of it all.

The most amazing thing about Kitano's portrayal is that he forces us Koreans to recognize our own fathers in this horrid monster. Kitano's performance in Blood and Bones is undoubtedly his best since Violent Cop, or possibly Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. It is a magnificent achievement that deserves all the accolades it will no doubt receive, and confirms his true genius as an actor.

Darcy Paquet: Documentaries Silent Forest and A State of Mind

I saw two documentaries at this year's PIFF: Hwang Yun's Silent Forest, about a trip by the filmmaker to China to search out traces of the Siberian Tiger (long since extinct in Korea); and A State of Mind, a film by British documentarist Stuart Gordon about two North Korean schoolgirls preparing to take part in the Mass Games, a huge spectacle of dance, gymnastics and acrobatics. Both films were enlightening; A State of Mind in particular is remarkable in showing the everyday lives of North Koreans, something that no other film in or outside North Korea is able to do in such informal depth.

Silent Forest, by the director of Farewell (which won the best Korean documentary award at PIFF 2001), is a loosely structured account of several conservationists who go to China after hearing year-old reports of tiger sightings at a remote village. Although more common in Russia, tigers and leopards are gravely depleted in China and in danger of disappearing completely. After talking to the villagers (whose feelings towards the animals were ambivalent at best, after several of their cattle were killed), the documentary goes on to look at the Chinese government's conservation policies, habitat destruction on Baekdu-san (a famous mountain along the Chinese-North Korean border popular with South Korean tourists), and finally the black market in animal products like bear's gall, that has spurned an industry of frightening scope (again, largely driven by the shopping habits of South Korean tourists). Though at times the documentary feels a bit disorganized, the manner in which it shows one issue's link with the next, and the next, is an appropriate way to illustrate a problem (endangered animals) that emerges from a long chain of causes and effects. Unfortunately, the film goes on after its emotional climax to dwell a bit too long on the personal feelings of the people who traveled with the director. It might have been much stronger if it had simply ended fifteen minutes sooner.

Silent Forest, by the director of Farewell (which won the best Korean documentary award at PIFF 2001), is a loosely structured account of several conservationists who go to China after hearing year-old reports of tiger sightings at a remote village. Although more common in Russia, tigers and leopards are gravely depleted in China and in danger of disappearing completely. After talking to the villagers (whose feelings towards the animals were ambivalent at best, after several of their cattle were killed), the documentary goes on to look at the Chinese government's conservation policies, habitat destruction on Baekdu-san (a famous mountain along the Chinese-North Korean border popular with South Korean tourists), and finally the black market in animal products like bear's gall, that has spurned an industry of frightening scope (again, largely driven by the shopping habits of South Korean tourists). Though at times the documentary feels a bit disorganized, the manner in which it shows one issue's link with the next, and the next, is an appropriate way to illustrate a problem (endangered animals) that emerges from a long chain of causes and effects. Unfortunately, the film goes on after its emotional climax to dwell a bit too long on the personal feelings of the people who traveled with the director. It might have been much stronger if it had simply ended fifteen minutes sooner.

A State of Mind is, in many ways, Stuart Gordon's reward for making the documentary The Game of Their Lives in 2002. A look at the past and present lives of the North Korean soccer players who reached the quarterfinals in the 1966 World Cup in Britain, the documentary was screened around the world but was particularly beloved in North Korea. "It's been shown something like ten times on North Korean TV," said Gordon at the Q&A session after the screening, "and there's only one TV station, so we had 100% ratings." The film's widespread fame in the country meant that Gordon had almost unrestricted access for his next film. "There were people who would accompany us, but never once did they try to stop us from shooting anything or influence the people we talked to," he said.

A State of Mind follows the training of two girls named Park Hyon Sun, 13, and Song Yon, 11, as they rehearse for their performance in the Mass Games. Extensive interviews with the girls and their families, footage of their practicing in unheated gymnasiums, and general shots of everyday life in North Korea make up the bulk of the film. At the end we get a spirited presentation of the Mass Games themselves, cut together in an extended, spirited montage to fast-tempoed (Western) music that captures well the spirit if not the letter of the games.

A State of Mind follows the training of two girls named Park Hyon Sun, 13, and Song Yon, 11, as they rehearse for their performance in the Mass Games. Extensive interviews with the girls and their families, footage of their practicing in unheated gymnasiums, and general shots of everyday life in North Korea make up the bulk of the film. At the end we get a spirited presentation of the Mass Games themselves, cut together in an extended, spirited montage to fast-tempoed (Western) music that captures well the spirit if not the letter of the games.

Moreso than the amazing performances in the Mass Games, it is the images of daily life in an ordinary Pyongyang family (which is to say, a quite privileged family compared to those in rural areas) that stick the longest. The words and actions of the girls and their families seem quite sincere. Their devotion to the country's leader Kim Jong-il is apparent, as is the North Korean people's deep distrust and fear of the U.S. government.

During screenings of the documentary at the Pyongyang Film Festival in September, the director was stunned to hear wild laughter from the audience at ordinary images like a faded North Korean flag painted on the side of a boat, or one of the frequent blackouts in the family's apartment. Later it was explained to him that North Koreans have never before seen their lives presented so plainly onscreen. An outside perspective, without the obligatory heroic tone of state TV and movies, had shown the viewers a radically different view of their lives.

In the West, virtually all of the information and images that we get of North Korea come filtered through competing ideologies and suspicions that run deep on both sides. A State of Mind is not meant to provide us with any answers to the North Korean "problem" (however you choose to phrase it), but instead to give a face to the ordinary people of the country. From watching this film, it's apparent that they live more than a world apart from the fast-paced, competitive society of South Korea.

Kyu Hyun Kim: October 9, 2004 / The Cannes Winners Open Talk / "My dream always ends here."

One of the wonderful things about the PIFF is the accommodation's proximity to the beach and the great seafood you can sample. Unfortunately, the seafood provided by the restaurants lining up the beachfront is pretty expensive, aside from abalone gruel. Fresh abalone is a pricey commodity everywhere, so $10 per each dish is not too bad. It is nice to have salt-smelling breeze and an open sea, albeit green-gray reflecting a cloudy sky, available to you for only a few minutes of walk from the madding crowd.

In the backyard of the posh Paradise Hotel the second Open Talk session was staged. Participating this time were three directors who scored prizes at this year's Cannes: Israel's Keren Yedaya, whose Or examines with an almost clinical eye the degradations visited on a mother and a daughter living in the working-class neighborhood in Tel Aviv, Thailand's Apitchapong Weerasethakul, the mastermind behind the controversial Tropical Malady, and Korea's Pak Chan-wook. The prepared seats were very quickly taken over not only by the early-bird film fans, but also by the members of the press who soon began to use the seats as footholds, blocking the views of the hapless latecomers. The eyes of the camera are as ubiquitous in the Paradise Hotel as in Dr. Mabuse's Hotel Luxor.

In the backyard of the posh Paradise Hotel the second Open Talk session was staged. Participating this time were three directors who scored prizes at this year's Cannes: Israel's Keren Yedaya, whose Or examines with an almost clinical eye the degradations visited on a mother and a daughter living in the working-class neighborhood in Tel Aviv, Thailand's Apitchapong Weerasethakul, the mastermind behind the controversial Tropical Malady, and Korea's Pak Chan-wook. The prepared seats were very quickly taken over not only by the early-bird film fans, but also by the members of the press who soon began to use the seats as footholds, blocking the views of the hapless latecomers. The eyes of the camera are as ubiquitous in the Paradise Hotel as in Dr. Mabuse's Hotel Luxor.

Moderator Kim Young-jin (Film 2.0) started off the discussion by confessing that the works of these three directors had very little in common. He raised the question of how "mainstream" the directors thought of their works. The director's answers to the question indeed underscored their differences in approach to cinematic art. Pak acknowledged that his films, featuring major stars and financed by large distribution companies, could be construed as "mainstream," even though he preferred to think of himself as operating in the "border" regions. Yedaya gave a thoughtful answer in which she distinguished between what makes Or difficult to approach stylistically (static camera, virtually no cut in a sequence) and what makes it politically marginalized. However, she evinced a strong desire to have her future films more accessible to as many viewers as possible. On the other hand, Weerasethakul insisted that his films are already "mainstream," since many people in Cannes, and now in Pusan, are interested in talking about them.

At this point Pak inquired Weerasethakul about the relationship between fine art and cinema. The latter turns out to be a well-known figure in the contemporary visual art scene, responsible for many renowned works of installation art. Weerasethakul's answer gave me the impression that, for him, cinema was a means to access emotional truths not readily available from other types of visual arts. Pak also asked Yedaya about the tears she shed upon receiving the Camera d'Or prize, eliciting a frank response from her about the difficulties of representing Israel as a filmmaker in a foreign setting. Yedaya sounded impressively sincere even when she asserted that her tears were really for those in Israel (by implication including Palestinians) who were still not free, still living under the shadows of oppression.

The oppression of the male authorities as well as scars of the past inflicted by them on a personalized scale were also explored in the New Currents presentation of That Charming Girl, the debut film by Director Lee Yun-gi. TV actress Kim Ji-soo plays Jeong-hye, a post-office worker who is a remarkable figure in terms of Korean cinema, one who does not seem to possess any desire, and responds to life's disappointments and irritations by... not responding to them. Filmed almost entirely with handheld camera and natural lighting and set in drab, ugly apartment buildings, That Charming Girl is sedate but hardly boring. Part of the film's attraction come from the thrill of anticipating when Jeong-hye will break the routine and reveal her inner turmoil, and from watching Kim's brave performance, withstanding extreme close-ups revealing the minute abrasions and scars on her face. When the "revelation" does come, it is inevitably disappointing in its predictability. I rather wish the film did not explain away the origins of Jeong-hye's quirky approach to life, but in any case, That Charming Girl, like its protagonist, is a shy but courageous film.

The oppression of the male authorities as well as scars of the past inflicted by them on a personalized scale were also explored in the New Currents presentation of That Charming Girl, the debut film by Director Lee Yun-gi. TV actress Kim Ji-soo plays Jeong-hye, a post-office worker who is a remarkable figure in terms of Korean cinema, one who does not seem to possess any desire, and responds to life's disappointments and irritations by... not responding to them. Filmed almost entirely with handheld camera and natural lighting and set in drab, ugly apartment buildings, That Charming Girl is sedate but hardly boring. Part of the film's attraction come from the thrill of anticipating when Jeong-hye will break the routine and reveal her inner turmoil, and from watching Kim's brave performance, withstanding extreme close-ups revealing the minute abrasions and scars on her face. When the "revelation" does come, it is inevitably disappointing in its predictability. I rather wish the film did not explain away the origins of Jeong-hye's quirky approach to life, but in any case, That Charming Girl, like its protagonist, is a shy but courageous film.

Three... Extremes, the second installment in the multicultural horror anthology series Three, was another hot item among the foreign press. From what I have observed after the screening, though, their response was more of a "huh?" than an unbridled enthusiasm. The three short films that constitute Three... Extremes are in their own ways as aggressively "artistic" as they are, indeed, extreme in content.

Fruit Chan's "Dumplings" takes a familiar subject matter for the Hong Kong horror film, explored with gusto in the notorious Untold Story, and couples it with another jaw-dropping taboo topic, that's sure to make a certain sector of Americans lose their lunch all over the theater seats. Chan's innovation is not a stylistic or visual one. It is rather a matter of attitude. Chan approaches this horrendous narrative with deep compassion for its female characters, including the "evil" rich woman (Pauline Lau) whose desire for surface beauty draws her to the "special dumplings" made by a mysterious Chinese expatriate living in a Hong Kong slum (Bai Ling). Filmed in soft hues and overlaid with gentle music score, "Dumplings" openly sides with the "monstrous" women who commit "unspeakable" acts in order to survive in the barbaric world designed and ruled by men.

Pak Chan-wook's "Cut" is a feverish, insane Neo-Gothic Theater of the Absurd, a nightmare collaboration between Jane Campion and Dario Argento adapting a rediscovered stage play by Jean Genet. Lee Byung-heon plays a handsome and wealthy film director whose life is overturned by an intruder (Im Won-hee) who will chop off his pianist wife's (Kang Hye-jung) fingers one by one with a hand-axe, unless the director proves that he is capable of doing something evil... such as strangling a kidnapped child to death. Even though "Cut" does showcase Pak's amazing mastery of the camera, production design and other aspects of the film medium, I was somewhat left cold by the film's content. It appears that Pak had the time to simply make one point, or wield just one finely-ground-axe, about the "vampiric" consumption of the underclass by the bourgeoisie. In films such as Old Boy and Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, Pak has maintained a fine balance between the absurd on one hand and the sincere on the other. In "Cut," he slips and tilts the balance decisively toward the absurd, weakening the film's impact in the process.

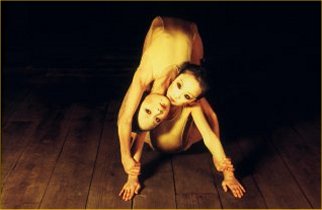

Miike Takashi's "Box," snowbound and desolate, is the work of the "quiet" Miike, the helmer of Audition and One Missed Call. "Box" confirms my view that the "quiet" Miike is five times the director of the "loud" Miike of the Shinjuku Yakuza trilogy, Ichi the Killer and Gozu. The beautiful Hasekawa Kyoko plays a writer of children's stories who keeps having the same nightmares over and over, of being wrapped up in plastic and squeezed into an impossibly small box, and then buried alive. Virtually dialogue-less and, in some key scenes, entirely soundless, the cumulative effect of "Box" is difficult to describe in words. The film is at once unabashedly poetic, deeply sad, unnervingly perverse: running through it all is the sense of absolute dread, held taut like a piano wire, the feeling that would be familiar to those who have seen Audition. But instead of the rampant sadism of Audition's ending, "Box" ends with one static shot that reveals the secret about the protagonist and her contortionist sister. It works beautifully either as a purely poetic image, another piece of the nightmare perhaps derived from the protagonist's subconscious, or as a key that opens all the doors to the mysteries we have previously witnessed.

Miike Takashi's "Box," snowbound and desolate, is the work of the "quiet" Miike, the helmer of Audition and One Missed Call. "Box" confirms my view that the "quiet" Miike is five times the director of the "loud" Miike of the Shinjuku Yakuza trilogy, Ichi the Killer and Gozu. The beautiful Hasekawa Kyoko plays a writer of children's stories who keeps having the same nightmares over and over, of being wrapped up in plastic and squeezed into an impossibly small box, and then buried alive. Virtually dialogue-less and, in some key scenes, entirely soundless, the cumulative effect of "Box" is difficult to describe in words. The film is at once unabashedly poetic, deeply sad, unnervingly perverse: running through it all is the sense of absolute dread, held taut like a piano wire, the feeling that would be familiar to those who have seen Audition. But instead of the rampant sadism of Audition's ending, "Box" ends with one static shot that reveals the secret about the protagonist and her contortionist sister. It works beautifully either as a purely poetic image, another piece of the nightmare perhaps derived from the protagonist's subconscious, or as a key that opens all the doors to the mysteries we have previously witnessed.

The segment "Box" is one of the few successful combinations of the poetic and the horrific I have seen, a mode with venerable predecessors including Jean Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast, Georges Franju's Eyes Without a Face and Carl Dreyer's Vampyr, working on the viewers almost subliminally. The 40 minute-"Box" may possibly be the best thing I have seen in the PIFF so far.

People at PIFF: Taro Goto, Assistant Festival Director of San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival

The San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival is North America's largest festival devoted exclusively to Asian American and Asian films. Launched in 1982, it is presented by a non-profit media arts organization called NAATA (National Asian American Telecommunications Association), and in its most recent edition it drew 27,000 admissions (up from 13,500 in 2001). Korean films screened at last year's festival include A Good Lawyer's Wife, Invisible Light and the documentary Being Normal. Taro was in Pusan to scout out new Asian films, and we caught up with him at the Pascucci cafe in the SfunZ building.

* Why did you decide to come to Pusan?

Pusan has really kind of developed in the last few years into the largest and most important Asian film festival. Although we typically visit Toronto and Vancouver to find the latest Asian films, we found that Pusan may be optimal in the sense that the works that appear at here are a lot fresher, and there are many premieres. That, coupled with the fact that a lot of the industry is here, and it's a great way to network with Asian film companies and other film programmers. And personally, I had never been to Korea. This is my first time.

Pusan has really kind of developed in the last few years into the largest and most important Asian film festival. Although we typically visit Toronto and Vancouver to find the latest Asian films, we found that Pusan may be optimal in the sense that the works that appear at here are a lot fresher, and there are many premieres. That, coupled with the fact that a lot of the industry is here, and it's a great way to network with Asian film companies and other film programmers. And personally, I had never been to Korea. This is my first time.

* How do you think the festival could improve?

I think the most frustrating thing, which a lot of people have already expressed, is the great difficulty in procuring tickets as an industry member. Even for screenings that are not sold out for the general audience, there seems to be a very small allocation for the pass holders. And for those of us who travel thousands of miles to this festival, to see as many films as we can in a short amount of time, that's proved to be extremely challenging. We end up not being able to get tickets for the shows we want to see, and then we go to the video room in hopes of being able to catch a few of these on tape, and they tend to be booked completely every day too, due to high demand. So I haven't been able to see as many films as I typically do at a film festival. But I think that the festival has probably already heard of these concerns from the guests, and that they'll do something to fix it. Other than that it's been a great festival. I've seen some good films.

* What's your favorite among the films you've seen here?

One was a pleasant surprise called University of Laughs. The description didn't appeal to me too much, but it was one of the few films I was able to get tickets to, so I went and saw it. It was a hilarious film, that reminded me a lot of the way the novel Catch 22 was able to make people laugh, but then precisely because it could make you laugh, also break your heart at the end too. It was a great performance by Koji Yakusho. Also, A State of Mind was an interesting documentary. We showed Game of Their Lives at last year's festival, so this new documentary is another possibility for us. (Mini-interview conducted by Darcy)

Kyu Hyun Kim: October 10, 2004 / "To exist is to have to seek forgiveness from others."

It's Sunday and the big events, parties and press coverage are reaching the fever pitch, as the Festival itself passes the midpoint and the weekend visitors to Pusan are nearing the endpoint of their sojourn.

I had requested for an interview with Pak Hae-il, the star of My Mother The Mermaid, but unfortunately the PIFF would not arrange for Korean stars and filmmakers to be interviewed by the press. The interviews with them must be set up separately via direct contact with their agents and representatives. Whew, as if I know how to get about doing that! I had to derive some satisfaction in seeing Pak's signature prominently displayed at the restaurant where I had dinner with Mr. Editor (Hey, I ate at the same restaurant Pak did!). I suppose any type of arrangement like this would be an additional nightmare for the organizers, but it is a missed opportunity and I stew for a while in my own juices of frustration.

I had requested for an interview with Pak Hae-il, the star of My Mother The Mermaid, but unfortunately the PIFF would not arrange for Korean stars and filmmakers to be interviewed by the press. The interviews with them must be set up separately via direct contact with their agents and representatives. Whew, as if I know how to get about doing that! I had to derive some satisfaction in seeing Pak's signature prominently displayed at the restaurant where I had dinner with Mr. Editor (Hey, I ate at the same restaurant Pak did!). I suppose any type of arrangement like this would be an additional nightmare for the organizers, but it is a missed opportunity and I stew for a while in my own juices of frustration.

In the evening I set out to the outdoor theater in the Yachting Club again, to watch the much-discussed but seldom-seen Japanese film Casshern. I quite liked the outdoor theater experience. The theater is basically a rock-and-roll stage that can accommodate more than 5,000 people with a huge, sail-like movie screen, slightly tilted toward the rows of folding chairs, flanked by towering speakers. There were some reporters and industry folks in the outdoor theater but the experience clearly belonged to the regular filmgoers, especially local residents of Pusan. The row in front of my seat was taken over by an extended family having a cinema night-out. On my right was a middle-aged gentleman with a female companion, draped in a blanket against the night chills. He seemed to understand Japanese, and I briefly wondered what is his backstory. Behind me was a group of chattering female students. None of them appeared to know what kind of film Casshern was. When the titles began to flash, the paterfamilias sitting in front of me was heard muttering, "Oh, it's a Japanese movie."

There was a pleasant piano concert that lasted 30 minutes, playing film scores from Il Postino, The Piano and other well-known and not-so-well-known films. A camera crew suddenly appeared out of nowhere and shone the harsh sodium light on the faces of the viewers. The gentleman to my right loudly protested, "Hey, can't you see we are in the middle of a concert?", supported by murmurs of assent. The volunteers soon arrived and politely and firmly asked the crew to beat it. I let out a small sigh of relief, seeing the Omnipresent Eye blinded, if only temporarily.

Casshern is a live-action remake of a 70s Japanese anime series, Shinzo ningen kyashan, mostly remembered for the slick, round design scheme and the extremely short miniskirt worn by the female protagonist, Luna, and not much else. The new film, directed by Kiriya Kazuaki, the former music video director and Utada Hikaru's husband, is a solid fantasy that remains, for better or worse, faithful to the kind of world-view and philosophy familiar to the Japanese anime. Bold and challenging in its looks and structure, Casshern uses a possibly confusing stream-of-consciousness modality to carry forward its epic plot, and creating astounding scenes of beauty and wonder, in its eclectic merging of 30s-style "steampunk" modernism (All flying vehicles are powered by propellers. The government agents carry around their own bulky, ugly version of cell phones), the painterly static scenery characterized by bright, Impressionist colors and the kaleiodscopic, high-contrast video images. It is also explicitly political, in its open evocation of the war against Iraq, Japan's Greater Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere and George Orwell's 1984 ("Eurasian Alliance").

Casshern is a live-action remake of a 70s Japanese anime series, Shinzo ningen kyashan, mostly remembered for the slick, round design scheme and the extremely short miniskirt worn by the female protagonist, Luna, and not much else. The new film, directed by Kiriya Kazuaki, the former music video director and Utada Hikaru's husband, is a solid fantasy that remains, for better or worse, faithful to the kind of world-view and philosophy familiar to the Japanese anime. Bold and challenging in its looks and structure, Casshern uses a possibly confusing stream-of-consciousness modality to carry forward its epic plot, and creating astounding scenes of beauty and wonder, in its eclectic merging of 30s-style "steampunk" modernism (All flying vehicles are powered by propellers. The government agents carry around their own bulky, ugly version of cell phones), the painterly static scenery characterized by bright, Impressionist colors and the kaleiodscopic, high-contrast video images. It is also explicitly political, in its open evocation of the war against Iraq, Japan's Greater Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere and George Orwell's 1984 ("Eurasian Alliance").

Casshern is the first film that I have seen that takes the peculiar, streamlined aesthetic of a video game and successfully infuses it into the film medium. The stunning sequence in which the "neo-sapiens" Tetsuya, a.k.a Casshern, single-handedly destroys a phalanx of about five hundred robots could have looked ludicrous but instead drew exclamations of "Wow!" and applause from the young viewers. The film's potential problems include the kind of verbose, over-directed non-ending typical of the epic anime (see Neon Genesis Evangelion or Akira) that will drive some viewers up the wall. Director Kiriya also behaves like a first-timer from a commercials and music video background, breaking up the rhythms of the narrative by wrapping it around the admittedly powerful set pieces. Overall, though, Casshern turns out to be anything but a dull blockbuster. While embracing its anime origins, the film manages to push the envelope in terms of what is possible as visual representation of the otherworldly on the cinematic medium.

Kyu Hyun Kim: October 11, 2004 / "Those who enter this area will never return to their homes."

One of the chronic problems with the PIFF is its awkward geographical split between two major sections of Pusan City, Haeundae, the beachfront resort, and Nampo-dong, the downtown. Even though a variety of transportation options are available (bus, subway, railway and taxicab), it still takes 45 minutes to one hour to move from one section of the city to another. This makes it impossible for anyone to, say, catch an 11 am screening of a feature film in Nampo-dong and then a 2 pm screening of another one at Haeundae Megabox, which is precisely why I had to miss out on Kore-eda Hirokazu's Nobody Knows.

Nampo-dong, right next to the famous Jagalchi fisherman's wharf, is as fully committed to the PIFF as it can. This afternoon, two stand-up comics were pelting a young film fan with quizzes about the festival in a mobile stage set up in the "PIFF Square." "Question! What is the opening film for the 9th PIFF?" "2046." "Excellent! Everybody give him a big hand! (Wah~)" "Get the answer to the next question right and you win the big prize!" "Okay here goes... what is the closing film for this year's festival?" "Um... Scarlet Letter." "HE'S GOT IT!" The gentleman is awarded with a brand-new digital camera and I can hear envious squeals mixed in the laughter and applause from the audience. In the PIFF Square leading to the open booths set up for production companies, advertising agencies, various associations and educational programs are the bronze "handprints" of the luminaries who had visited the Festival in previous years. Surprisingly, a large number of them are directors, not stars. The Greek cineaste Theo Angelopoulos, the subject of a special retrospective, will leave his imprint on the PIFF Square this year. I linger over Yu Hyeon-mok's handprints and take a picture (left). I also stop over at the Jeonju International Film Festival booth, tempted to buy its elegantly designed T-shirt. Instead I end up purchasing a book collection of interviews about independent Korean cinema. More weight to be added to the already heavyset suitcase: academic habits die hard.

Nampo-dong, right next to the famous Jagalchi fisherman's wharf, is as fully committed to the PIFF as it can. This afternoon, two stand-up comics were pelting a young film fan with quizzes about the festival in a mobile stage set up in the "PIFF Square." "Question! What is the opening film for the 9th PIFF?" "2046." "Excellent! Everybody give him a big hand! (Wah~)" "Get the answer to the next question right and you win the big prize!" "Okay here goes... what is the closing film for this year's festival?" "Um... Scarlet Letter." "HE'S GOT IT!" The gentleman is awarded with a brand-new digital camera and I can hear envious squeals mixed in the laughter and applause from the audience. In the PIFF Square leading to the open booths set up for production companies, advertising agencies, various associations and educational programs are the bronze "handprints" of the luminaries who had visited the Festival in previous years. Surprisingly, a large number of them are directors, not stars. The Greek cineaste Theo Angelopoulos, the subject of a special retrospective, will leave his imprint on the PIFF Square this year. I linger over Yu Hyeon-mok's handprints and take a picture (left). I also stop over at the Jeonju International Film Festival booth, tempted to buy its elegantly designed T-shirt. Instead I end up purchasing a book collection of interviews about independent Korean cinema. More weight to be added to the already heavyset suitcase: academic habits die hard.

Nampo-dong's historical Daeyoung Cinema was the site for the screening of the Viet Nam-themed horror film R-Point and the Q & A session with its director Kong Su-chang, also the screenwriter for Tell Me Something, The Ring Virus and another Viet Nam War-themed film White Badge. R-Point is a straightforward supernatural horror that does not rely on "clever" plot twists (No need to worry that it will replicate the then-already overused surprise ending from Jacob's Ladder) to ensnare the viewers. Its chief strength lies in an excellent ensemble cast led by Kam Woo-seong (Marriage Is a Crazy Thing) as the cynical captain and Son Byeong-ho (Oasis, Mokpo The Gangster's Paradise) as the tough second-in-command. Although nothing special as a horror film, R-Point is best appreciated as an almost theatrical drama of moral corruption and political critique, in which the "situational imperatives" of being in a war gradually undermine the characters' compassion and capacity for reasoning.

The Q & A session for Director Kong was, as per such sessions go during the PIFF, intense and critical. There was a question about the location, done mostly in Kampuchea under less than perfect conditions. Kong revealed an ironic fact that the abandoned old French colonial hotel, effectively used as the cursed Vietnamese temple in the film (see photo, right), was designated by UNESCO as a cultural monument to be protected. There was an unexpectedly poignant moment when, speaking of the young (teenage) Korean soldiers killed in action and whose bodies were never shipped to Korea, Director Kong began to weep. Undaunted, the predominantly female questioners continued to throw tough questions, including one on continuity gaffes and errors in editing. I asked Kong about the directorial devices used to film the powerful climactic sequence, a sort of cranked-up version of Reservoir Dogs' Mexican stand-off. He said the sequence was extensively rehearsed, and was filmed twice, first with the static cameras and one more time with the Steadycam. Finally, Kong acknowledged that the film he really wants to make is a Bildungsroman, and that he is not particularly interested in genre cinema.

The Q & A session for Director Kong was, as per such sessions go during the PIFF, intense and critical. There was a question about the location, done mostly in Kampuchea under less than perfect conditions. Kong revealed an ironic fact that the abandoned old French colonial hotel, effectively used as the cursed Vietnamese temple in the film (see photo, right), was designated by UNESCO as a cultural monument to be protected. There was an unexpectedly poignant moment when, speaking of the young (teenage) Korean soldiers killed in action and whose bodies were never shipped to Korea, Director Kong began to weep. Undaunted, the predominantly female questioners continued to throw tough questions, including one on continuity gaffes and errors in editing. I asked Kong about the directorial devices used to film the powerful climactic sequence, a sort of cranked-up version of Reservoir Dogs' Mexican stand-off. He said the sequence was extensively rehearsed, and was filmed twice, first with the static cameras and one more time with the Steadycam. Finally, Kong acknowledged that the film he really wants to make is a Bildungsroman, and that he is not particularly interested in genre cinema.

Rare for the Korean Panorama section at the PIFF is a sophomore effort by an up-and-coming director. My Mother The Mermaid, directed by Park Heung-shik (I Wish I Had a Wife), is a disarming, gentle drama that manages to transcend its hoary Back to the Future premise but cannot quite inoculate itself against the outbreak of cute-itis. Above all else, it is a star vehicle for Jeon Do-yeon, who deftly essays a dual role that includes truly impressive split-screen interactions. Perhaps too self-consciously "heart-warming," the film is nonetheless worth seeing just for Jeon's incredible star performance, although the veteran actress Go Doo-sim's portrayal of the crude, obstinate mother is perhaps equally remarkable.

Kyu Hyun Kim: October 12, 2004 / Director Lee Yoon-ki mini-interview / "Yes, of course we accept Choco-pies."

After catching the old Korean-Hong Kong co-production Schoolmistress at 10 am, I rushed toward the Paradise Hotel where the directors of the New Currents selections were being introduced to the press. Twelve low-budget Asian films competed in this section, mostly debut features from young directors springing from intriguingly diverse backgrounds (from commercials, journalism, acting, even engineering science). The films and filmmakers are:

Sanctuary |

The Cat Leaves Home (Japan), dir. Iguchi Nami |

It was heartening to see that these filmmakers, some of whom had made their debut films under excruciatingly difficult circumstances (one of the selections was submitted on a Betamax videotape), received a good deal of press coverage. I certainly hope that their films and by extension their future careers get much exposure and boost by their participation in the PIFF. Promoting the new cinematic talent of Asia is something the PIFF can truly excel at like no other film festival in the world.

Even though I had arrived late, I managed to mix in with a coterie of reporters surrounding director Lee Yoon-ki and peppering him with questions about This Charming Girl (see the October 10 Report for a take on the film itself). The following is a compressed version of the questions and answers with Director Lee from myself and other reporters.

*Where did you get the inspiration for the character of Jeong-hye? Is there any particular message or meaning behind your film?

A good part of Jeong-hye's character has been developed in the original short story [note: by Woo Ae-ryung]. Some more thought went into building the backstory of the character, what to take out for the film version, and what to add.

As for any "message" behind this film, I thought it was important not to obsess over specific themes or messages. In fact, I attempted to avoid the elements that can be reduced into feminist or social criticism, or any trace of pedantic preaching. That also meant not reaching for an easy reconciliation or forgiveness at the end of the film.

*The extended close-ups used for the main actress must have been difficult to film. There are also shots that go on for long time.

Yes, it was a tough call for her [Kim Ji-soo]. I believe she did a great job, though.

These shots are not necessarily done in such a way due to aesthetic principles or calculations. We valued, more than anything else, the moment a character is contemplating something inside, and we are not sure where she would choose to take it. Preserving that moment's tension was a priority. Some viewers apparently felt that these shots sort of tested their patience.

*Is there a plan for a general release?

We are thinking of a March 2005 release. We believe this represents a good window of opportunity, although a lot can happen between now and then.

*This is a bit of a strange question, but do you love cats? I also thought that the film could be titled "Invisible Cat."

Yes, I love cats. Ah, Invisible Cat sounds nice, but you know, there was another movie called Take Care of My Cat and the cat as a sign for an independent and on-her-own female character has become a sort of cliche, so I wouldn't have used that title.

After the interview I had a few more minutes of discussion with Director Lee. He revealed that his dream project was the kind of historical drama hitherto never attempted in Korean cinema. It would have to be a big-budget production with assistance or collaboration from foreign filmmakers. Here's hoping that Director Lee, whose film was awarded the New Currents Award by the unanimous decision of the jury, will get funding and support needed to realize his dream project.

In the early evening was an impressively well-attended screening of the sole Korean film included in Critic's Choice section, Shin Sung-il Is Missing. Filmed mostly in black and white digital video, Shin Sung-il is a minor-league Bunuellian horror-fantasy that combines droll, deadpan humor and overt surrealism. One has to come equipped with a certain level of tolerance for "arthouse" aesthetics, such as in-your-face religious symbolism, quasi-Brechtian devices that call attention to themselves and the lack of narrative resolution, to properly appreciate this film.

In the early evening was an impressively well-attended screening of the sole Korean film included in Critic's Choice section, Shin Sung-il Is Missing. Filmed mostly in black and white digital video, Shin Sung-il is a minor-league Bunuellian horror-fantasy that combines droll, deadpan humor and overt surrealism. One has to come equipped with a certain level of tolerance for "arthouse" aesthetics, such as in-your-face religious symbolism, quasi-Brechtian devices that call attention to themselves and the lack of narrative resolution, to properly appreciate this film.

I quite liked its sense of humor and the cutely sincere performance by the child actors, but watching this film I could not shake the feeling: 1) that it is bound to be read as an allegory for North Korea (although Director Shin Jae-in denied any consciousness on her part about the parallel, and I believe her), and 2) that the kind of frightening Christian fundamentalist cult depicted in the film, I am sure, not only exists in real-life in Korea (and in the United States) but also is probably taking children's lives away at this very moment. For these reasons, I could not quite embrace the intellectually satirical tone of the film.

There is no question that Director Shin is a talent to watch out for, although I hope she is not entirely serious about making Shin Sung-il Is Missing Part 2: Kim Kap-soo Is Doomed (?!) as her follow-up project.

Kyu Hyun Kim: PIFF Retrospective

For this year's retrospective screenings, the PIFF expanded upon last year's theme. Chung Chang-hwa, the focus of the 8th PIFF Korean Cinema Retrospective, was a Korean director who spent a large part of his career making martial arts films in Hong Kong. This year's nine selections are all movies co-produced by Hong Kong and Korea between the mid-60s and early 80s. A few of these films, such as the epic The Last Woman of Shang and the ultra-exploitative The Bamboo House of Dolls, belong to the digitally cleaned-up Show Brothers collections, now owned by Celestial Pictures. Other films such as When Taekwondo Strikes are appreciated by the cognoscenti of the kung fu cinema for their kitschy attributes, wildly incongruent elements or exotic settings. These are the kind of works Quentin Tarantino would quote in one of his movies, and then some North American fans would scramble to track them down in gray market video copies, based on that "reputation." Yet others are completely obscure and presumably survive only as Korean-dubbed prints preserved in the Korean Film Archive. The titles are as follows:

The Last Woman of Shang |

The Bamboo House of Dolls (1973) |

Like Mr. Editor last year, I had planned to see all of the retrospective films but of course that turned out to be a complete impossibility. I could not even schedule my itinerary to grab the films in the order of historical importance, which should have put the pre-Yushin-dictatorship-Korea and early-Shaw Brothers-Hong Kong co-production The Last Woman of Shang and The Goddess of Mercy on the top of my list. Naturally, these two were the ones I missed. Sigh.

[Darcy interjects at Kyu Hyun's request to write his thoughts on The Goddess of Mercy. This is a big budget film that was made by Shaw Brothers and Shin Sang-ok's leading production company Shin Films. It features not only a famous cast, elaborate costumes, and impressive location shooting, but also some nifty special effects that had the audience chuckling. Two versions of this film were made: the scenes with the lead actress were shot twice, once with Hong Kong actress Li Lihua and again with Korean actress Choi Eun-hee. Sadly, the Korean version has been lost, and so the Hong Kong version was screened here. The film tells the story of a King's daughter who converts to Buddhism and eventually rebels outright against her tyrannical father, leading a group of prisoners to a new land. For people familiar with the stars of 1960s Korean cinema it was interesting to see them perform in a different setting, dubbed into Mandarin Chinese. Like most of the films in the retrospective it was hard to call it a real discovery, however. The story of how it was made is more interesting than the film itself]

Sammo Hung was a special guest star at this year's PIFF, partly to receive recognition as a major contributor to the Korean-Hong Kong co-production, looking dapper and exuding the confident air of a senior statesman of Asian genre cinema. It is a pretty well known fact that Jackie Chan also worked as an extra in his salad days in Korean action films and can speak rudimentary Korean largely for that reason.

Young Sammo Hung (characteristically cast as a villain, complete with a set of false teeth), Jackie Chan and Yuen Biao (you blink and you miss him) are cast in supporting roles in Hand of Death (pictured left), co-directed by John Woo and Kim Chung-yong. It is hands-down the best martial arts film in the retrospective. Its power owes much to John Woo's brisk and no-nonsense direction. Woo does not waste any time with dumb comic relief or extended scenes of characters spewing forth monologues about their undying loyalty to the Ming dynasty, and just go for the (Hung-choreographed) action. Another factor contributing to the film's success is its brilliant cast. Even though the taekwondo expert Dam Do-ryang (Tan Tiao-ling, or Dorian Tan) is the nominal hero, the film is more or less taken over by James Tien (forever cast as Bruce Lee's second banana in the latter's vehicles, here able to show off his formally-trained kung fu moves) as the charismatic Manchu villain. Even John Woo's own cameo appearance is handled intelligently.

Young Sammo Hung (characteristically cast as a villain, complete with a set of false teeth), Jackie Chan and Yuen Biao (you blink and you miss him) are cast in supporting roles in Hand of Death (pictured left), co-directed by John Woo and Kim Chung-yong. It is hands-down the best martial arts film in the retrospective. Its power owes much to John Woo's brisk and no-nonsense direction. Woo does not waste any time with dumb comic relief or extended scenes of characters spewing forth monologues about their undying loyalty to the Ming dynasty, and just go for the (Hung-choreographed) action. Another factor contributing to the film's success is its brilliant cast. Even though the taekwondo expert Dam Do-ryang (Tan Tiao-ling, or Dorian Tan) is the nominal hero, the film is more or less taken over by James Tien (forever cast as Bruce Lee's second banana in the latter's vehicles, here able to show off his formally-trained kung fu moves) as the charismatic Manchu villain. Even John Woo's own cameo appearance is handled intelligently.

South Korean locations, especially Buddhist temples, are extensively used in both Hand of Death and Duel to Death. The technically spectacular climax of Duel, the debut feature of Ching Siu-ting (Chinese Ghost Story), is shot in the so-called Suicide Rock found in Taejongdae, Pusan (see the two photos below). For some reason, Korean locations add a sense of desolation and a flavor of Daoist renunciation of the ordinary life to these films, which is a bit odd for someone who grew up in the country, like myself.

Schoolmistress, on the other hand, is a rare example of Korean filmmakers importing a Hong Kong star and stitching a typical melodrama plot around her. In this case, Li Ching plays a half-Korean English teacher in an all-girl high school, in fact a half-sister to her favorite charge, played by An In-sook. While the male stars Shin Sung-il and Shin Young-gyun loiter around and make serious faces, the movie is dominated by two actress-stars (They share a full-blown dating montage sequence, whereas the male lead Shin and Li Ching are reduced to exchanging expository dialogues in a bar. Hmm). An, spectacularly charming, is the real heroine of the piece, cast as a precocious high school girl patronized by every adult she encounters. She carries the plot forward, transforms from a naive adolescent to a vengeful femme fatale and even has a semi-erotic undressing scene. Despite the Korean dubbing, you can also catch glimpses of intriguingly different styles of melodramatic acting by Hong Kong and Korean stars in Schoolmistress.

Unexpectedly well made is the period-piece horror Black Hair, directed by Shin Sang-okk's protege Chang Il-ho and starring Korean leads Jin Bong-jin, Nam Seok-hun and Lee Hye-suk. This story of a man who sells out his loyal wife for fame and fortune, despite some ridiculous "special" effects (the ghost of the dead wife seems to be wearing a boxer's mouthpiece if one looks closely), is an effective hybrid genre effort, with expressive lighting, atmospheric production design and solid performances from the leads. Surprisingly well preserved in spite of its obscurity, Black Hair deserves at least a DVD release with better English subtitles. (While we are at it, does the Korean Film Archive have the uncut print of Insa yeomu, the notorious Korean-Filipino co-production?)

Unexpectedly well made is the period-piece horror Black Hair, directed by Shin Sang-okk's protege Chang Il-ho and starring Korean leads Jin Bong-jin, Nam Seok-hun and Lee Hye-suk. This story of a man who sells out his loyal wife for fame and fortune, despite some ridiculous "special" effects (the ghost of the dead wife seems to be wearing a boxer's mouthpiece if one looks closely), is an effective hybrid genre effort, with expressive lighting, atmospheric production design and solid performances from the leads. Surprisingly well preserved in spite of its obscurity, Black Hair deserves at least a DVD release with better English subtitles. (While we are at it, does the Korean Film Archive have the uncut print of Insa yeomu, the notorious Korean-Filipino co-production?)

The Rescue, on the other hand, is a standard wuxia pian with little Koreanness in it. Full of the cliches expected from a historical drama of its kind, including secret passages, torture dungeons, heroes in disguises and sudden switches of allegiances ("I am a Han Chinese, too!"), The Rescue is primarily worth seeing as an early example of wire action technology and trampoline-based acrobatics. (They make us appreciate just how much Ching Siu-ting and Yuen Woo-ping have accomplished through these techniques through the '70s and '80s) It did not help that the print used for the screening was an apparently censored one, with several frames of gore snipped out from each and every action sequence.

Likewise, When Taekwondo Strikes is badly dated and more valuable as a historical artifact than as a martial arts entertainment. It is devoid of the grace and aplomb of the better films of its kind like Hand of Death. Sammo Hung, Angela Mao Ying (Bruce Lee's sister in Enter The Dragon) and the Korean expatriate Hwang In-sik gamely provide support for the rather uncharismatic lead Jhoon Rhee, who appears to be speaking English dialogue. (I still remember a jingle from the TV commercial for his Washington D.C.-based taekwondo academy. "Nobody bothers me~~.")

The Bamboo House of Dolls is simply and shamelessly exploitative, with little pretensions about the serious examination of Japanese wartime atrocities and an embarrassing chunk of blonde-white-woman fetishism.

Speaking of Japan, even though absent except as the country of origin for their cartoonish villain figures, its cinematic legacy cast a lengthy shadow over the films in the retrospective. It is pretty obvious that Black Hair, for instance, is an unacknowledged remake of The Ghost of Yotsuya, right down to the details such as the poison administered to the heroine that destroys only half of her face (with plot elements imported from the "Black Hair" episode from Kobayashi Masaki's Kwaidan), and that Duel to Death is a souped-up version of the ninja action genre developed in Japan by, among others, the novelist Yamada Futaro (the dead giveaway is the horizontal split from the head to groin!). In Duel to Death, in fact, the cynical, nihilistic samurai hero of 60s Japanese period pieces is reconceived as a Chinese sword-master (Damian Lau), fighting against pigheadedly "patriotic" Japanese who behave more like the Ming dynasty loyalists.

Speaking of Japan, even though absent except as the country of origin for their cartoonish villain figures, its cinematic legacy cast a lengthy shadow over the films in the retrospective. It is pretty obvious that Black Hair, for instance, is an unacknowledged remake of The Ghost of Yotsuya, right down to the details such as the poison administered to the heroine that destroys only half of her face (with plot elements imported from the "Black Hair" episode from Kobayashi Masaki's Kwaidan), and that Duel to Death is a souped-up version of the ninja action genre developed in Japan by, among others, the novelist Yamada Futaro (the dead giveaway is the horizontal split from the head to groin!). In Duel to Death, in fact, the cynical, nihilistic samurai hero of 60s Japanese period pieces is reconceived as a Chinese sword-master (Damian Lau), fighting against pigheadedly "patriotic" Japanese who behave more like the Ming dynasty loyalists.

Perhaps the PIFF retrospective could one day tackle the still difficult-to-breach topic of Japanese "presence," both implicit and explicit, in the Korean cinema of yesteryear.

Some presentations were marred by the bad quality of English subtitles: "Imperial Army" (hwang-gun in Korean) in Taekwondo, for instance, is rendered as "Hwang Army" at one point, and as "Yellow Army" at another (Not that the colonial-period Korea presented in Taekwondo has any semblance to real history, and yet). Next year whoever is responsible for English subs in either PIFF or Korean Film Archive should pay a bit more attention to their quality.

Awards and Final Statistics

Programming: 262 films from 63 countries

Total Audience: 166,164 tickets (84.8% seating rate)

Guests: 5,638 accredited guests (domestic + intl)

Hand Printing: Theo Angelopoulos

Seminars: "Garin & the Next Generation: New Possibility of Indonesian Cinema," "Rediscovering Asian Cinema Network: The Decades of Co-production Between Korea & Hong Kong,"

New Currents Award: This Charming Girl (Korea) by Lee Yun-ki. "The jury of New Currents section of the 9th PIFF unanimously decided to award This Charming Girl directed by LEE Yun-ki (Korea). The very restrained style captured the psychological wounds of the urban life of a charming woman." Special Mention to Sanctuary (Malaysia) by Ho Yuhang.

* Jury Members: Sergey Lavrentiev (festival director, Sochi Int'l Film Festival, Russia), Dito Tsintsadze (director, Georgia-Germany), Fruit Chan (director, Hong Kong), Apichatpong Weerasethakul (director, Thailand), Kim So-young (film scholar, Korea).

FIPRESCI Award for best new Asian film: Soap Opera (China) by Wu Er-shan. "This year's awardee is Soap Opera by WU Er-shan for its shocking ability to reflect the violence, indifference and pressures that modern urban societies mercilessly inflict upon citizens pushing them beyond their limits."

NETPAC Award for best Korean film: 3-Iron (Korea) by Kim Ki-duk. "The NETPAC (Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema) Award is presented to the best Korean feature film by the NETPAC jury. We estimate the brave interpretation of realities which open the new horizon in life-world. The narrative is also fresh and has some surprising developments. 3-Iron suggests also deep desire of human being to live in another level of the world." Special Mention to So Cute by Kim Soo-hyun.

Sunje Fund Award (10m won) for best Korean short film: (tie) Punk Eek by Song Kwang-ju. "Punk Eek is the only short film in the Wide Angle category with an experimental quality. A satire on superficiality and hypocrisy of Korean middle class expressed through intellectual montages is impressive." / Gold Fish by Park Shin-woo. "Psyche of a boy, alienated and uneasy due to his parents' feud, is expressed through images that border on reality and fantasy; detailed representation of solitude through usage of colors deserves recognition."