1997

From left: "The Letter", "The Contact", "Beat", "Green Fish"

Looking back now at 1997, we can see the early signs of a rebirth in Korean commercial cinema. For the first time since 1993, two Korean films broke the 600,000 admissions mark: melodrama The Letter and urban love story The Contact. Of the two, it was The Contact which struck young viewers as something new and different, with its slick visuals and use of the internet as a plot device. Two other popular films from 1997 have also turned into cult hits, having a strong influence on the future development of Korean cinema. Beat by Kim Sung-soo established its young leads Jung Woo-sung and Ko So-young as major stars, while also demonstrating the potential of youth-oriented films. No. 3 is the forerunner of today's gangster comedies, and it introduced such major comic actors as Song Kang-ho and Park Sang-myun.

On the artistic side, despite comparatively weaker offerings by directors like Im Kwon-taek and Kim Ki-duk, 1997 will be remembered for the debut of Lee Chang-dong, who has developed into one of Korea's undisputed top directors. Other highlights include Park Chul-soo's manic ob/gyn drama Push! Push!, Byun Young-ju's documentary Habitual Sadness and Jang Sun-woo's hard-hitting Timeless, Bottomless, Bad Movie.

Reviewed below: Green Fish (Feb 7) -- Beat (May 10) -- Bad Movie (Aug 2) -- No. 3 (Aug 2) -- The Contact (Sep 13) -- Chang (Sep 13) -- Motel Cactus (Oct 25).

| Korean Films | Seoul Admissions | Release Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Letter | 724,474* | Nov 22 |

| 2 | The Contact | 674,933 | Sep 13 |

| 3 | Chang (Downfall) | 411,591 | Sep 13 |

| 4 | Beat | 349,781 | May 10 |

| 5 | Hallelujah | 310,920 | Aug 9 |

| 6 | No. 3 | 297,617 | Jul 10 |

| 7 | Change | 167,235 | Jan 18 |

| 8 | Green Fish | 163,655 | Feb 7 |

| 9 | Mister Condom | 157,032 | Mar 1 |

| 10 | The Hole | 141,717 | Nov 1 |

| All Films | Seoul Admissions | Release Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Lost World (US) | 1,001,279 | Jun 14 |

| 2 | Con Air (US) | 979,100 | Jun 28 |

| 3 | The Fifth Element (Fr/US) | 857,752 | Jul 16 |

| 4 | The Letter (Korea) | 724,727* | Nov 22 |

| 5 | Face/Off (US) | 716,107 | Aug 9 |

| 6 | The Contact (Korea) | 674,933 | Sep 13 |

| 7 | Air Force One (US) | 663,415 | Sep 13 |

| 8 | Men In Black (US) | 662,106 | Jul 12 |

| 9 | Jerry Macguire (US) | 448,393 | Feb 1 |

| 10 | Downfall (Korea) | 411,591 | Sep 13 |

* Includes tickets sold in 1998.

Market share: Korean 25.5%, Imports 74.5% (nationwide)

Films released: Korean 59, Imported 380

Total attendance: 47.5m admissions

Number of screens: 497 (nationwide)

Exchange rate (1997): 1016 won/US dollar

Average ticket price: 5,017 won (=US$4.94)

Exports to other countries: US$492,000

Average budget: 1.1bn won + 0.2bn p&a costs

Source: Korean Film Council (KOFIC).

Short Reviews

These are some reviews of the features released in 1997 that have generated the most discussion and interest among film critics and/or the general public. They are listed in the order of their release.

The year 1997 saw the debut of a major filmmaking talent in Lee Chang-dong, a novelist who first became involved in the film industry as co-writer of two films by Park Kwang-su, To the Starry Island (1993) and A Single Spark (1996). These works deal with various aspects of 20th-century Korean history, but Lee's debut film Green Fish is a very contemporary story set in the rapidly-developing outskirts of Seoul. The film's stark mood and controlled filmmaking made an immediate impression on local critics, and it also won the Dragons & Tigers Award for new Asian directors at the 1997 Vancouver International Film Festival.

The film's hero Makdong (meaning "youngest sibling") returns to his hometown after completing his compulsory two-year military service. He tries to find work to help support his family, which seems on the edge of disintegration, but with the area overrun by new apartments, little is available. Ultimately he takes a trip into Seoul and finds lucrative but dangerous work in organized crime.

The film's hero Makdong (meaning "youngest sibling") returns to his hometown after completing his compulsory two-year military service. He tries to find work to help support his family, which seems on the edge of disintegration, but with the area overrun by new apartments, little is available. Ultimately he takes a trip into Seoul and finds lucrative but dangerous work in organized crime.

Green Fish features an all-star cast and crew, although many of them were not well-known at the time. The actors include Han Suk-kyu, Moon Sung-keun, Shim Hye-jin, Song Kang-ho, Jung Jin-young (Hi, Dharma), Oh Ji-hye (Waikiki Brothers), Myung Kay-nam (My Beautiful Days), and even Han Suk-gyu's brother, Han Sun-gyu. It was produced by what is now Korea's biggest film studio in Cinema Service, and executive produced by Kang Woo-suk (Two Cops). The film's producer, Yeo Kyun-dong, is both an actor (Love Bakery) and a director (La Belle) in his own right. The cinematographer, Yoo Young-kil, is Korea's most famous -- he died in 1998 shortly after finishing Christmas in August. The assistant director and co-writer, Oh Sung-wook, went on to make Kilimanjaro (2000).

Most striking about Green Fish, as with Lee's subsequent features, is its emotional force, which is expressed while abstaining from conventional melodramatic techniques. He paints a gloomy view of Korean society and the turbulent nature of its development. This can be seen perhaps most clearly in the inner conflicts and problems faced by Makdong's family. A scene towards the end of the film, in which a family picnic disintegrates into chaos, shows how unstability has kept the family from growing close, or providing each other with any emotional support.

Lee has become a stronger and more refined filmmaker over time, and his later features Peppermint Candy (2000) and Oasis (2002) carry more of his personal style than Green Fish. Nonetheless Green Fish stands well on its own, and it offers an impassioned if pessimistic view of Korea that lends depth to the genre of gangster films. (Darcy Paquet)

Beat is a film that doesn't age well. It may have been a player in 1997, as evidenced by it reaching #4 on that year's list of box office leaders, but watching it almost 20 years later I would have to recommend it with hesitations, or with provisos of the necessary context of the history of the South Korean film industry. The prime culprit for Beat falling out of fashion might be the fashion. Whan's overalls scream sartorial choices from the 90's that are best forgotten. Whan (the debut film for Im Chang-jung, Sex Is Zero 1 & 2, Twilight Gangsters) even does the let-one-loop-run-free bad idea. Then there is the dialogue as it comes across in English translation which might keep non-Korean-speakers from connecting to some of the characters on any deep level. And the efforts to affect coolness on to the characters can be over-extended at times, such as the time spent lingering on the first lighting of cigarettes between Min (Jung Woo-sung, A Moment To Remember, Cold Eyes) and Tae-soo (Yu Oh-Seong, Friend, Champion) that makes this post-fight masculine moment of shared lung cancer almost seem post-coitus.

But this was 1997, only a year after things really started to get going for South Korean Cinema, that liminal area between the Korean New Wave and New Korean Cinema. As a result, I cut this period some slack. In addition, there is so much energy palpitating through this film, and scenes where the choreography and cinematography choices work, such as the fight scenes which pulsate with vibrancy. Even the sex scene between Min and Sunny (Sa Hyeon-jin, Last Present, The Wig) has more dramatic impact because it's shown through visuals, through bodies enraptured, rather than dialogue. As Min races through the freeways of Seoul on his fancy crotch rocket, when he lets go of his handlebars you can feel that his character has let go of anything rational for everything visceral. It is these scenes where Kim Sung-soo orchestrates a Beat we all can dance to.

But this was 1997, only a year after things really started to get going for South Korean Cinema, that liminal area between the Korean New Wave and New Korean Cinema. As a result, I cut this period some slack. In addition, there is so much energy palpitating through this film, and scenes where the choreography and cinematography choices work, such as the fight scenes which pulsate with vibrancy. Even the sex scene between Min and Sunny (Sa Hyeon-jin, Last Present, The Wig) has more dramatic impact because it's shown through visuals, through bodies enraptured, rather than dialogue. As Min races through the freeways of Seoul on his fancy crotch rocket, when he lets go of his handlebars you can feel that his character has let go of anything rational for everything visceral. It is these scenes where Kim Sung-soo orchestrates a Beat we all can dance to.

If much of the dialogue was cut out and we were just allowed to watch the friendship triangle of centerpoint Min with the two lower edges of Tae-soo and Whan, and the romantic dyad of Min with Romi (Ko So-young, Love Wind, Love Song, APT), the film might be more watchable years hence. Beat might then be a fully re-watchable film like Lee Myung-se's masterpiece on movement Nowhere To Hide and his equally delightful meditation on motion Duelist. Instead, to find pleasure in a Beat repeat, I find it best to fast forward through scenes where the characters aren't moving, as if your remote control is Min's motorcycle, parking at the fight scenes, the scenes racing through Seoul, or the scenes where Romi is dissembling. But then I interrupt my impressions with the humbling fact that this film is not meant for me. It is meant for Koreans and I must always open to the autochthonous interpretations.

Beat introduces us to young thugs Min and Tae-soo as they wreak havoc on local gangs. Hoping for something beyond pugilism for her son, Min's mom (prominent South Korean marijuana legalization advocate Kim Bu-seon, To You, From Me, Monster) moves Min to another school, severing these best of buddies. At the new school, Min meets the class glue-sniffer Whan and they become fast pals. Whan can't fight like Min, but he fights for Min's loyalty. It is through Whan's selling of Min at auction to be a 'slave date' that Min meets the high-class Romi. Taking this slave date seriously, Romi gives Min a beeper to be at her beck and call to which Min gladly obliges. Anxious to maintain her class privilege, Romi urges Min to improve his studies to win her undying love and likely that of her parents. But Min can't keep up with those expectations. And it turns out Romi can't either. After Min tries different ways to go legit with Whan through a restaurant venture and with Romi through a shared apartment, eventually Min finds himself having to reconsider Tae-soo's multiple offers to join him in working for a bigger gang boss.

Besides reminding us of the beeper culture that was so popular in South Korea in the 90's, the awkward scenes at the nightclub will remind you that South Korea wasn't always the epitome of Korean Wave cool. The hip hop dance skills we expect of KPop now came later after intense practice. Much of the soundtrack is full of imitative punk, heavy metal, and hair band varieties to underscore the energy of youth on display. (I did like the brief appearance of a tune from Roo'ra during a karaoke scene.) The fashion and the music seems copied rather than authentically expressed, the style choices are ones folks cringe at when reminiscing through pictures of their past selves. (Although that yellow jacket Romi rocks in one bar scene wouldn't be out of place on any of the young ladies of 2NE1.)

In the end, it is the energy on display in Beat that stays with me. Those scenes are not awkward. They are vibrant, full of life even when the characters are engaging in actions that could easily bring about their death. Beat provides glimpses of the masculine archetypes actors Jung and Yu would continue to bring to the screen in later roles. The film often fails to hit that perfect beat, boy, but the film is a wonderful precursor of what is to come in masculine comedies like Attack the Gas Station and violent dramas like Friend where South Korean cinema hit its stride of glocalization, captivating global audiences while still remaining tied to local culture. Beat fails to keep a constant successful rhythm, but it is the potential that matters where this film is concerned. (Adam Hartzell)

"I'm bored." This is the announcement made by one of the young women 'characters' of Bad Movie while in a dance club she and her female friends have trespassed outside of business hours. She makes this statement just as she begins to violently throw the bar stools off from the tabletops on which they reside. In an interview in 1993 (found in Seoul Stirrings: 5 Korean Directors), director Jang Sun-woo told Tony Rayns, ". . . I feel a strong impulse to make a film about the young generation now, about what makes them different" (p33). Bad Movie is that film. Thankfully, Jang shows us that the young generation (at the time he made the film) is more than just "bored". Because that wouldn't make them any different from any other generation.

As is occassionally the case with Jang, this film refuses to follow a narrative that will allow for easy processing of the goings on within the film. The title of the film is "Bad Movie" after all. (In the United States, the film is known as Timeless, Bottomless, Bad Movie.) In the introduction of the film where we would expect to find the credits, we are presented with what can be called "Anti-credits". "No fixed script", "No fixed actors", "No fixed photography", etc., take their place on the screen to let us know that the screen is about to be filled with real life individuals-cum-characters that spawn from the lives they live as bad kids breaking through South Korea's "economic miracle" facade just like the IMF crisis that began the year before this film was released. Due to its portrayal of violent and obnoxious resistance to authority and disregard for basic human decency, standard film narrative, and high production quality, (this latter aspect cannot be excused for lack of funds since Jang had a considerable budget for this film), one can see justification in Kyung Hyun Kim's claim that "The film is quite possibly the most controversial and ruptured film text in the history of Korea" (The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema, p.187).

As is occassionally the case with Jang, this film refuses to follow a narrative that will allow for easy processing of the goings on within the film. The title of the film is "Bad Movie" after all. (In the United States, the film is known as Timeless, Bottomless, Bad Movie.) In the introduction of the film where we would expect to find the credits, we are presented with what can be called "Anti-credits". "No fixed script", "No fixed actors", "No fixed photography", etc., take their place on the screen to let us know that the screen is about to be filled with real life individuals-cum-characters that spawn from the lives they live as bad kids breaking through South Korea's "economic miracle" facade just like the IMF crisis that began the year before this film was released. Due to its portrayal of violent and obnoxious resistance to authority and disregard for basic human decency, standard film narrative, and high production quality, (this latter aspect cannot be excused for lack of funds since Jang had a considerable budget for this film), one can see justification in Kyung Hyun Kim's claim that "The film is quite possibly the most controversial and ruptured film text in the history of Korea" (The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema, p.187).

As Kim notes, the presumed violence and nihilism of wayward youth are a staple for the bad boys of national cinemas like Jang. Still Kim elucidates that "there is an inherent resistance against barbarism that lurks around the violent impulses of the youth . . ." (p188) that keeps Bad Movie from fully validating the initial reactions one is likely to have with this film. Jang wasn't simply trying to make a lot of money here or "boost" his festival cred. (In fact, Kim argues, in an argument difficult to summarize here in such limited space, Jang was seeking to shatter his own iconicity.) The scene that most resonates with the "inherent resistance against barbarism" is the B-Boy stance that breaks down in the film. These kids demonstrate the considerable Hip Hop dance skills that KPop will exploit throughout Asia in the 00's as these emerging men call each other to the dance floor to represent their cultural capital. However, something deeper is going on. One of these boys is reluctant to drop his kinesthetic knowledge. He is obviously struggling with something unvoiced. His friends notice their friend is troubled and they proceed to show their concern by motioning to get their friend to toss his cares off with a few well-orchestrated pops and locks and windmills. Eventually he brings his careful choreography to the dance floor. But the weight within still remains despite the efforts of his friends. We will follow this young man into the restroom as he engages in a patient, Matthew-Barney-esque ritual to kill himself. This ritual is disrupted by a friend's actions and that weird demand masculinity makes that boys and men show they care about fellow males through ridicule. Jang shows here better than anywhere else in this film, and perhaps in most other films about youth's penchant to destroy itself, that something lurks underneath the surface of the nihilism, violence and supidity of youth just as much as something lurks underneath the joy, playfulness, and creativity. Yet Jang refuses to let us know anything more than that something is lurking. He won't tell us what is lurking. Perhaps this is what is most damning about this film in the minds of its critics, (which, at times, I include myself among, going back and forth in my feelings about this film). Professor Kim again - such refusal upsets "the moral conventions of feature films" (p188).

The young adults that zoom around this film - literally in the sense of the purposely sped up film that occurs at points - are not the only people followed. Jang also spends time with "street sleepers" or homeless people who reside in Seoul Station, providing a connection to the wasting and fulfilling lives of the youths and the lives of these older men. (Song Kang-ho fans will have to add Bad Movie to their online DVD rental queues, since Song makes an appearance as a fellow "street sleeper" taking a group of proselytizers up on their offers to clap your hands if you love Jesus.)

Bad Movie is one of many South Korean films that generates so many questions I would love a real-time forum in which to ask. Since much is made about the film being motivated by real lives of these non-actors acting, the audience might have understandable questions about what is real and not real, about what is right and not right. This is valuable on a philosophical level helping us return to "documentaries" better aware that the observer cannot help but impact that which she or he observes. But these questions are also on an ethical level regarding concerns about these young adults revisiting some horrifying events from their alluded real lives without knowledge of the tactics that professional actors learn to utilize to protect their emotional selves when playing such characters. Plus, many of the homeless followed appear to be what mental health workers call "dual-diagnosed", that is, mentally ill along with being alcoholics. This brings up serious ethical issues regarding their ability to consent to their being filmed.

Bad Movie, like most of Jang's oeuvre, makes me very uncomfortable. Well aware that the unexamined life is the comfortable one, I think his films are worth living through regardless of how icky they might make me feel and as much as, (or because), I might require multiple conversations with other viewers and my ethical head to ever fully comprehend what Jang and his co-creators have realized here. (Adam Hartzell)

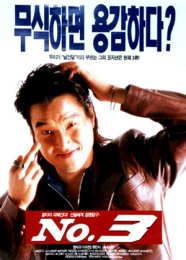

Similar in tone and attitude to Scorsese's Goodfellas or John Huston's Prizzi's Honor, No. 3 does not quite scale the same height of greatness that these mobster "comedies" attain, but is a unique and fascinating film nonetheless, well deserving of its cult reputation. A terrific showcase for its ensemble cast, many of whom have since become top stars, No.3 is a great example in support of the thesis, "when a movie is well cast, half the job is done."

Director Song Neung-han takes an approach somewhat unusual for a Korean film: instead of having a complex plot or situational setups drive forward the narrative, he focuses on character portrayal. And what characters! Tae-joo, played by Han Suk-kyu, is a long-haired, scowling SOB with a serious case of inferiority complex. Choi Min-shik as the prosecuting attorney Ma Dong-pal, is far more foul-mouthed and mean-tempered than the gangsters he deals with, an obvious parody of Choi Min-soo's role in the ever-popular miniseries Hourglass. Park Sang-myun is "Ashtray," a porcine thug with the brainpower of a lab mouse, carrying a sun-burst-design crystal ashtray in his pants... as a weapon of deadly assault. Lee Mi-yeon plays Virginia Woolf-quoting Tae-joo's wife, who unexpectedly obtains literary success, in the course of having an affair with a chipmunk-like poet nicknamed Rimbeaud. And finally, Song Kang-ho is indescribably hilarious as the psychotic Jopil, a third-rate assassin who keeps botching up his job at the critical moment. (The scene where he punishes his long-suffering underlings for talking back to him is one of the funniest moments in Korean film history, although the English subtitles can hardly convey what makes Song Kang-ho's delivery of lines so comical)

Director Song Neung-han takes an approach somewhat unusual for a Korean film: instead of having a complex plot or situational setups drive forward the narrative, he focuses on character portrayal. And what characters! Tae-joo, played by Han Suk-kyu, is a long-haired, scowling SOB with a serious case of inferiority complex. Choi Min-shik as the prosecuting attorney Ma Dong-pal, is far more foul-mouthed and mean-tempered than the gangsters he deals with, an obvious parody of Choi Min-soo's role in the ever-popular miniseries Hourglass. Park Sang-myun is "Ashtray," a porcine thug with the brainpower of a lab mouse, carrying a sun-burst-design crystal ashtray in his pants... as a weapon of deadly assault. Lee Mi-yeon plays Virginia Woolf-quoting Tae-joo's wife, who unexpectedly obtains literary success, in the course of having an affair with a chipmunk-like poet nicknamed Rimbeaud. And finally, Song Kang-ho is indescribably hilarious as the psychotic Jopil, a third-rate assassin who keeps botching up his job at the critical moment. (The scene where he punishes his long-suffering underlings for talking back to him is one of the funniest moments in Korean film history, although the English subtitles can hardly convey what makes Song Kang-ho's delivery of lines so comical)

This brilliant cast is ably assisted by Song Neung-han's excellent screenplay (winner of multiple awards, including the 1997 Blue Dragon prize for the best screenplay). Even a conventional scene such as a bedroom spat between Tae-joo and his wife has a bite not commonly felt in other Korean films. ("Do you know why there are no children in gangster movies?") No. 3 is also replete with ingenious, quirky touches that enliven the more mundane proceedings: gigantic barcode patches are stitched to the "21st century" prisoners: "supratitles" appear above the characters, as if they are thought balloons in a cartoon, whenever they use pretentious classical Chinese phrases and proverbs.

Like many recent Korean films, No. 3 has some troubles maintaining a consistent tone. "Ashtray's" antics are way too bloody and disturbing for a predominantly comic vehicle, Han Suk-kyu's character rather unconvincingly changes his tune in the climax, and a few attempts at satirizing the obsessions and hypocrisies familiar to the Koreans, such as their ambivalent feelings toward Japanese, fall flat. Still, even when faltering, No. 3 has far more gumption and displays greater intelligence than many similarly-themed Korean films: compared to it, Attack the Gas Station is just plain silly, and Public Enemy is revealed to be a witless vigilantism drama. Finally, though, I am hesitant to recommend No. 3, as smart and savvy as it is, to anyone who is just getting curious about Korean cinema. Like a spicy cold noodle dish, it is something of an acquired taste, and requires some degree of familiarity with Korean culture on the part of a viewer to fully appreciate its tang. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

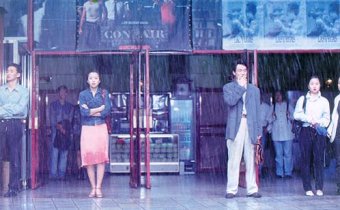

The Contact was a breakthrough hit in 1997 that catapulted Jeon Do-yeon to stardom and took many Korean viewers by surprise: they had never expected such an urbane, meticulously constructed, intelligent melodrama from Korean filmmakers. The Contact is indeed an immensely well-crafted film: it cannot be brushed off as a gimmick movie about an internet romance ("A boy and a girl chat in the internet: they fall in love: will they recognize each other when they meet offline?"), or a star vehicle for Jeon and Han Suk-kyu, wonderful as they are in their respective roles. However, even after watching the film three times, and for each time being thoroughly absorbed and entertained by it, I still find the film a bit artificial and pandering to the fantasy of its target audience, which the producer admitted was young female workers ("office ladies").

The film is masterfully orchestrated by Director Jang Yoon-hyun. He had studied cinema in Hungary and co-produced and edited a powerful leftist polemic Before the Strike,(1990) and yet for his own directorial films, The Contact and Tell Me Something, (1999) he chose to make big-budgeted commercial products operating within the boundaries of melodrama and horror-thriller genres. For that reason, and perhaps also due to the paucity of his directorial output (he has been more active as a producer in recent years) Jang is seldom discussed in the same breaths with such auteurs as Im Kwon-taek, Kim Ki-duk and Hong Sangsoo. However, in my opinion, Jang is one of the most visually interesting directors currently working in Korean cinema. I am always intrigued by his color schemes, (in The Contact, blues and purples contrasted to beiges and greens, for instance) that call to mind the Italian masters of 1960s and 70s, and his blockings and camera setups are interesting without calling attention to themselves (Greatly aided by his Director of Cinematography Kim Seon-bok, also responsible for Shiri [1999], JSA [2000] and My Sassy Girl [2001]). Yet, Jang is not a stylist-for-the-sake-of-style-only: his "pictures" are for the most part subordinated to the art of storytelling. Indeed, he is several miles ahead of many younger, supposedly more visually-oriented Korean directors in terms of the economy, efficiency and originality of his visual idioms.

The film is masterfully orchestrated by Director Jang Yoon-hyun. He had studied cinema in Hungary and co-produced and edited a powerful leftist polemic Before the Strike,(1990) and yet for his own directorial films, The Contact and Tell Me Something, (1999) he chose to make big-budgeted commercial products operating within the boundaries of melodrama and horror-thriller genres. For that reason, and perhaps also due to the paucity of his directorial output (he has been more active as a producer in recent years) Jang is seldom discussed in the same breaths with such auteurs as Im Kwon-taek, Kim Ki-duk and Hong Sangsoo. However, in my opinion, Jang is one of the most visually interesting directors currently working in Korean cinema. I am always intrigued by his color schemes, (in The Contact, blues and purples contrasted to beiges and greens, for instance) that call to mind the Italian masters of 1960s and 70s, and his blockings and camera setups are interesting without calling attention to themselves (Greatly aided by his Director of Cinematography Kim Seon-bok, also responsible for Shiri [1999], JSA [2000] and My Sassy Girl [2001]). Yet, Jang is not a stylist-for-the-sake-of-style-only: his "pictures" are for the most part subordinated to the art of storytelling. Indeed, he is several miles ahead of many younger, supposedly more visually-oriented Korean directors in terms of the economy, efficiency and originality of his visual idioms.

One problem I have with The Contact is its inability to transcend the melodramatic codes embedded in Korean cinema, despite its sophistication. The screenplay by Jo Myeong-joo (Love Wind Love Song [1999], Over the Rainbow [2002]) tries way too hard to make it difficult for the two leads to hit off, and once they hit off, to keep the audience at the edge of their seats in expectation of their physical encounter. The big payoff, expertly filmed and edited, is crowd-pleasing to be sure, but by then chunks of melodramatic cliches, including that overused bag of chips-on-the-shoulder known as the "trauma resulting from a friend/lover/sibling's suicide," have been mixed into the narrative. Another problem is that I cannot muster much sympathy for the character of Dong-hyeon, played by Han Suk-kyu. Yes, Han's acting skills and star charisma do strive to make Dong-hyeon appealing, but I still find the latter rather charmless, excessively moody, pedantic, and male-chauvinistic. (I admit that there is something about Han Suk-kyu lecturing women in non-honorific Korean that makes me feel like I am listening to a dentist's instrument working on a root canal... which I would like to think of as my "Dr. Bong problem") After having seen the film three times, I am still doubtful that its lead characters could have a decent chance at a romance, much less a happy marriage.

Dressed in jeans, overalls and ugly pastel-color shirts and her hair done in a decisively unflattering perm for most of the movie, Jeon Do-yeon as Su-hyeon makes a daring choice of presenting herself as a plain, homey figure, perhaps even subject to bouts of girlish delusion. Her gamble pays off handsomely, as we cannot help but be drawn to her warm, thoughtful personality. However, I must confess that I find Choo Sang-mi's character Eun-hee much more interesting than Su-hyeon. Eun-hee is an independent career woman, a go-getter who is open about the nature and direction of her sexual desire, and quite free from clinging to a done relationship. (The lead characters, in contrast, spend nearly the entire running time waffling about their "traumatic" past love affairs) An "upgraded" version of Eun-hee can be seen played by Lee Young-ae in Hur Jin-ho's exquisite One Fine Spring Day (2001).

The Contact is not quite a landmark classic of Korean cinema it is sometimes taken to be. Still, as two hours of smart, high-quality entertainment, it deserves to claim its position among the cream of the crop from Korean films of the 1990s. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

I have a confession to make: I don't much like Im Kwon-taek's films. Oh, I respect them: the old man learned his trade doing hackwork, and worked his way up to arthouse fare and international fame. He knows how to make a movie, and I'm never bored when I watch one. Between his expertise and that of his longtime cinematographer Jung Il-sung, Im delivers a product that panders both to my movie-fan's craving for visual impact (with gritty sex for seasoning), and to my pointy-headed intellectual's craving for pretension (with gritty sex to show his, um, artistic integrity).

But I feel a coldness in Im's work that puts me off in the end, and I also feel him trying to prove that he's an auteur of world-class cinema like Ingmar Bergman at his worst, though on the whole I like Im better than Bergman. (No, I haven't seen all 100 of Im's movies has anyone? but I've seen enough of those that put him on the map to have formed a working opinion.) He takes an oddly detached view of Korean life, as if he were an anthropologist describing Han exotica to titillate outsiders except that the outsiders are mostly Koreans themselves.

Chang (aka Downfall) isn't one of Im's best-known films, but it's a good example of his virtues and his limitations. It's the story of an orphan girl (Shin Eun-kyung, My Wife Is A Gangster) who's abducted into prostitution in the 1970s. Her career is a microcosm of life in South Korea's bars and brothels, as she goes from house to house and city to city. For a while she runs a place of her own before tumbling back down to the bottom; by that time she's given up hope of ever getting out of the Life. She meets a studly guy who gives her pleasure for the first time (in the film, anyway), but he turns out to be just another pimp, living off her earnings to make sure she never saves enough to buy herself out. She marries a rich older man, but he treats her as his own private whore for the use of guests and business associates, and when his college-age son discovers her background, she's back where she started. (She mentions that her husband even lent her to foreigners, which is a reminder that we see no foreigners onscreen. There's more to prostitution in Korea than the women who service American soldiers.)

Chang (aka Downfall) isn't one of Im's best-known films, but it's a good example of his virtues and his limitations. It's the story of an orphan girl (Shin Eun-kyung, My Wife Is A Gangster) who's abducted into prostitution in the 1970s. Her career is a microcosm of life in South Korea's bars and brothels, as she goes from house to house and city to city. For a while she runs a place of her own before tumbling back down to the bottom; by that time she's given up hope of ever getting out of the Life. She meets a studly guy who gives her pleasure for the first time (in the film, anyway), but he turns out to be just another pimp, living off her earnings to make sure she never saves enough to buy herself out. She marries a rich older man, but he treats her as his own private whore for the use of guests and business associates, and when his college-age son discovers her background, she's back where she started. (She mentions that her husband even lent her to foreigners, which is a reminder that we see no foreigners onscreen. There's more to prostitution in Korea than the women who service American soldiers.)

Of course there's a shy, odd-looking country boy (Han Jong-hyeon) from Cholla Province, with lank shoulder-length hair, denim jacket, khaki pants, and clodhopper shoes. His name is Gil-yeong. He lets her sleep because she seems so tired, then looks at her body by matchlight; at dawn he slips out after the friend who brought him there. But later, when she's moved to a new house, she passes a machine shop where he's working, and they start seeing each other. "Are you okay?" she asks him, "Did you get a disease?" "It's almost cured now," he reassures her. They love each other, but they never seem to consider becoming a couple themselves. Gil-yeong always tracks her down, and keeps trying to find the town of Young-eun's early memories, a rural Eden that is gone forever because of the modernization and urbanization of Korea. (Gil-yeong is pulled over by the police three times in the movie for not wearing a helmet while riding his motorcycle; it's almost a running joke, maybe a tiny act of recurring resistance.)

There are other indications that Im intended Chang as an allegory of recent Korean history. Chae Young-eun's career spans two rather turbulent decades, and TVs are always on in the background. When President Park Chung-hee is assassinated, the women are blase. "Sure," comments one as Park's funeral plays on TV, "he made it easy for us to be whores." We're also told later in the film that it's hardly necessary to kidnap orphans into sex slavery anymore, with all sorts of women even respectable middle-aged ajummas voluntarily turning tricks for pin money and diversion from their boring middle-class lives.

Young-eun moves again, to a seaside town, and as Gil-yeong arrives on a rainy day, the accession of Chun Du-hwan to the Presidency is announced on TV. Young-eun is living with a taxi driver who's helping to pay off her debt. They plan to marry, and she invites Gil-yeong to come. He congratulates her; no jealousy. But her marriage fails, as does Gil-yeong's engagement to a yangban girl And so it goes, through the opening of the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, with archival footage of President Roh Tae-woo kicking off the festivities. (Once again I was struck by Roh's resemblance to George W. Bush, only with Buddha earlobes.) I enjoyed the appearance of various Korean character actors and stars to be, especially Park Sang-myeon, who would appear again with Shin Eun-kyeong in My Wife Is A Gangster. Here he's a heavy who runs a bar where Young-eun works, without the charm and humor he'd later display.

Probably the most striking aspect of Chang is Im's use of a cutaway set for the brothel, allowing him to track from room to room and peek at one john after another, their quirks and weaknesses. (It's a common feature in films about prostitution, from Lizzie Borden's Working Girls to Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho, to show the humorous fetishes of the customers, so very unlike the wholesome voyeurism of the filmmaker and audience.)

Im's next film after Chang was his version of the Korean evergreen Chunhyang, which won lots of awards and established him definitively on the international scene. Chunhyang fits with and comments on its predecessor, contrasting the photogenic and refined kisaeng of the good old days with the degraded bar girls nowadays. But kisaeng were at the top of the sex trade in their day; there were also lower-class, cut-rate working women (and men) who weren't as glamorous. Chunhyang's Cinderella-style happy ending contrasts with the unhappy one of Young-eun, who if she's not Everywoman is much more typical of her trade. (Duncan Mitchel)

What to say about Motel Cactus, Park Ki-yong's debut film? Well, it can be summed up in one name, Christopher Doyle. As cinematographer for this film, he becomes the focus over that of the story, characters, or direction. Known to most of us through his legendary work with Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai (Chungking Express (1994), Fallen Angels (1996), Happy Together (1997), In The Mood for Love (2000)), Doyle is what, if anything, shines from within this film. He plays with shower screens, droplets of water, smoke, and mirrors that themselves are smoke and mirrors to hide the lack of a powerful story. This is an exercise in cinematography. And as a film critic, whose name I've since forgotten, once said to me, if all you can say about a film is that you liked the cinematography, you are not talking about a great film.

The story within this display of Christopher Doyle's skills consists of four separate stories all happening within the walls of Room 407 of Motel Cactus. The first concerns a mistress and her lover celebrating the mistress's birthday. The second consists of two college students making a student film. The third, for all we know, are two people who like to drink a lot. And the final couple consists of past lovers reunited after one has returned on holiday after immigrating to Canada. Each couple behaves within a come-here/go-away pattern of ambivalence about their relationship.

The story within this display of Christopher Doyle's skills consists of four separate stories all happening within the walls of Room 407 of Motel Cactus. The first concerns a mistress and her lover celebrating the mistress's birthday. The second consists of two college students making a student film. The third, for all we know, are two people who like to drink a lot. And the final couple consists of past lovers reunited after one has returned on holiday after immigrating to Canada. Each couple behaves within a come-here/go-away pattern of ambivalence about their relationship.

Outside of the two students in the second story, the characters in the other three stories, the first, third, and fourth stories, are connected by an actor/actress from a previous story. The first story features Jin Hee-kyung and Jung Woo-sung, the third Jin Hee-kyung and Park Shin-yang, and the fourth Lee Mi-yeon and Park Shin-yang. Perhaps, since played by the same actors and actresses, the characters are meant to be the same characters. But the plot, what there is of one, really doesn't present such as necessary.

Besides Doyle's pretty pictures, what can be said about this film is that it highlights a consistent presence in Korean Film: The Love Motel. Every other Korean Film, at least from what we see on the festival circuit, seems to make reference to Love Motels, or in Korean, "yogwan." With a significant number of Korean singles living at home with their families and such families often including their ever-present grandparents, the opportunities to explore the sexual realm of one's relationships are limited. In the land where I dwell, the United States, more singles live apart from their families and most colleges have coed dorms. Even before all that, the latchkey lives caused by the economic need for two-income earning parents or double-shift working single-parents allows for many opportunities away from family supervision where American youths can explore their sexual selves. In Korea, the Love Motel is the rare escape from the panopticon of eyes that Korean society can be. This being the case, the Love Motel can provide much fodder for developing characters and storylines in Korean Films such as Hong Sangsoo's Oh, Soojung! ("Virgin Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors") (2000) and Jang Sun-woo's Lies (2000).

But that almost feels like I'm forcing an importance upon Motel Cactus. Really, it's just a vehicle for Christopher Doyle. Thankfully, this was not a sign of things to come for Park Ki-yong. As Darcy has noted in his review of Park's second film, Camel(s) (2002), Park would later impress us with his ability to do more with less. (Adam Hartzell)

Other films released in 1997

3PM Bathhouse Paradise (dir. Kwak Kyung-taek), Baby Sale (dir. Kim Bon), Barricade (dir. Yoon In-ho), Blackjack (dir. Chung Ji-young), Ghost Mama (dir. Han Ji-seung), Habitual Sadness, (dir. Byun Young-ju), The Hole (dir. Kim Sung-hong), Holiday in Seoul (dir. Kim Ui-seok), The Letter (dir. Lee Jeong-guk), The Man With Flowers (dir. Hwang In-roe), Mister Condom (dir. Yang Yoon-ho), Push! Push! (dir. Park Chul-soo), Repechage (dir. Lee Kwang-hoon), Trio (dir. Park Chan-wook), Wild Animals (dir. Kim Ki-duk), Wind Echoing In My Being (dir. Jeon Soo-il).