An Interview with Mo Ji-eun

by Paolo Bertolin

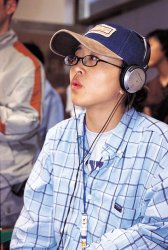

The recent vague of Korean cinema has consistently surprised international audiences and critics not only for the growing success of its commercial production and the artistic relevance of its authors' creations, but also because the national industry has bred an unprecedented generational renewal, unparalleled in any other country. Debut filmmaker Mo Ji-eun marks a further step forward in this direction, lowering once again the average age of Korean directors, as she has completed her first feature film at the age of only 26. Furthermore, as a femme director, she also represents the increasing relevance of the feminine presence in the cinematic industry of Korea. We met her last year at Udine's Far East Film Festival, where she presented the international premiere of her romantic comedy, A Perfect Match.

How did your career as a filmmaker begin? Have you attended film courses?

I graduated in cinema at Dongguk University. Then, to increase my preparation I enrolled in the Korean Academy of Film Arts. During this period I was training by making storyboards on many different film productions, some relevant ones too. While I was completing my studies I also started working on my first feature, A Perfect Match, and I graduated from the Academy just this year.

Who are the directors you most admired as a student and whose work really made you want to become a director yourself?

Well, there are lots! The first who come to mind and who really made me want to make my own films are Im Kwon-taek, Andrei Tarkovski and Ken Loach.

As a film written and directed by a woman dealing with female characters, A Perfect Match undeniably bears comparisons with Jeong Jae-eun's Take Care of My Cat, although that film's characters were slightly younger than those of yours. Has Jeong's film influenced your work in any way?

The similarities mainly rely on the fact that these two films deal with young Korean women. Nevertheless, I think this is only an apparent similarity, as there is no real connection between them. Both the narrative material and the storyline diverge and the only real common element is that they portray the situation of contemporary Korean women.

However, there is a striking similarity between the two films, at least to a Westerner's eyes, in the way they portray how young Korean women tend to gather into very close teams of friends that support one another when one is facing sentimental or existential crisis.

However, there is a striking similarity between the two films, at least to a Westerner's eyes, in the way they portray how young Korean women tend to gather into very close teams of friends that support one another when one is facing sentimental or existential crisis.

In Korea we have a proverb that is key to the understanding of our culture and the way we behave. It says that a seven year-old boy and a seven year-old girl must not sit side by side. This segregationist attitude is considered recommendable for any age, so a sort of taboo against the gathering of gender-mixed groups of friends still persists in our country. It is usually very difficult to see groups of friends made up of both sexes in Korea, even among the youngest generations.

Still, the protagonist of A Perfect Match keeps a very close friendship with a male childhood friend, who once promised her that if she reaches thirty without finding a husband, he would marry her. These one-on-one friendships can be considered as an exception to the general rule?

In general, outside of close groups of friends only made up of people of the same gender, it is instead quite common to have close friendships between a single male and a single female. In a certain way, this taboo involves the gathering of groups of friends, while it doesn't affect the relationships between single people. In any case, it remains quite inconceivable to imagine a male element to be introduced into an all-female gathering of friends, and vice versa. Those kinds of friendships can survive only outside the gender-oriented circles of friends.

At the beginning of the film, the three friends are coming out of the screening of a romantic comedy: two of them are quite annoyed by the excessive sentimentalism of the third one, who's crying like a river. What does this prologue represent for a film that actually belongs to the genre of romantic comedy?

Well, first of all you have to know that the Korean cinema industry generally considers romantic comedies as doomed to box office failure. This assumption has become a sort of superstition, and only very recently has the market proved it wrong! You can take the beginning of my film as a sort of luck-bringing lightning rod!

From a far more general perspective, you have to consider that usually we Koreans tend to keep our feelings to ourselves and not show them overtly to other people. Korean people are very discreet and also tend to abstain from physical contact. It is quite curious but in Korea when people are interviewed at the entrance of a multiplex about what choice they're going to make, they never answer that they're going to see a romantic comedy. Romanticism and sentimentalism are generally kept as private, secret and sometimes even denied. That does not mean that Koreans do not have strong feelings, but they live with them as an embarrassment and try not to confess them.

So, the tears that girl cries at the beginning of the film might be judged as a form of improper behaviour in Korea?

There is a certain dose of irony in that sequence, because any one of us knows that while watching a film it is natural to let your feelings flow, and thus even being moved to tears by a film is a totally natural experience. This girl might seem excessive in her reaction, but in the end she's just honest, she expresses her intimate feelings with honesty. Of course, for Korean audiences their emotional reactions towards romantic films are embarrassing, but this doesn't mean they don't like them. Many people prefer not to go to the theatre and maybe have to hold back from crying in public, they just rent or buy romantic films on DVD to watch them all alone at home and let their emotions flow free.

I'd like to ask you how you conceived a couple of quite inventive sequences. First, the one where you visualise the texts of the SMS's that the protagonist and one of her friends exchange when they discover that the man they're meeting is not up to their expectations. Incidentally, this is a device that was present in Take Care of My Cat too, although here words humorously travel through the frame. Secondly, the one where you insert animated figures representing the actors that the protagonist's friends describe as their ideal men.

Both these sequences came from the same necessity. In my film there are no spectacular sequences or narrative developments, so the framing and point of view in my camerawork could have been quite limited in register. Of course, this is a film much more concerned with narrative than camerawork, nevertheless, I was afraid of getting bored while shooting it and at the same time I was afraid I would bore my audiences, so I chose to include some variations. Regarding the visualisation of the SMS, I can tell you that while I was making my film, I still had not seen Take Care of My Cat; in fact, it was a friend of mine who told me that the same idea was used in that film. I think the use I make of this device is different, since in A Perfect Match it is meant to create a comic effect.

Both these sequences came from the same necessity. In my film there are no spectacular sequences or narrative developments, so the framing and point of view in my camerawork could have been quite limited in register. Of course, this is a film much more concerned with narrative than camerawork, nevertheless, I was afraid of getting bored while shooting it and at the same time I was afraid I would bore my audiences, so I chose to include some variations. Regarding the visualisation of the SMS, I can tell you that while I was making my film, I still had not seen Take Care of My Cat; in fact, it was a friend of mine who told me that the same idea was used in that film. I think the use I make of this device is different, since in A Perfect Match it is meant to create a comic effect.

Regarding the other sequence, the original concept was to reproduce images recalling TV news. If you look at that sequence, in fact, you will notice that I have framed the actresses who are talking strictly from a frontal point of view, as if they were anchorwomen, so that the animation on their sides might look like the picture or animation used to visualize the topics of breaking news. But, instead of news, here it is a matter of actors and ideal men!

Both the beginning and the end of the film, plus the sequence where the bunch of friends debate on Tell Me Something, correspond to the image we have in the West of Korea as a cinephile nation. Is it just a stereotype or does this reflect a certain truth?

Korean people from older generations are not interested in cinema and do not go to theatres very often. Younger people are instead very fond of films, both national and foreign ones, and they go to the movies very often. So they love to speak about their favourite movies and actors in their everyday life. Cinema is undoubtedly the favourite form of entertainment among Korean youths: it is a demonstrated fact that they prefer cinema even to rock music concerts!

Paolo Bertolin, UDINE April 2003