An Interview with Kim Jee-woon

by Paolo Bertolin

Kim Ji-woon is among those contemporary Korean directors who don't need an introduction. Since his debut with The Quiet Family (1998), his films have met with commercial success and admiration from domestic audiences, while garnering him a cult following among Asian films fans all over the world. His ambitious contemporary adaptation of a popular Korean folk tale in A Tale of Two Sisters (2003) was his first film to be granted theatrical release in most international markets. Last year, his most recent effort, A Bittersweet Life (2005), was invited to Cannes Film Festival, where it screened out of competition and established Kim as one of those few directors capable of registering with both audiences and critics, both at home and abroad. The following conversation with Kim took place in March 2006 at the 4th Florence Korean Film Festival, where a retrospective of his work took place.

A Bittersweet Life looks quite different from your previous films, which all fall into the genre categories of comedy and horror. What are, in your own view, the differences and elements of continuity with respect to your previous output?

It was not on purpose that I made A Bittersweet Life different from my previous films. I just wanted to explore the noir genre, tell the story of this character, and tackle the themes that you see in it. By bringing together these needs, the end result is something quite different from anything I have done before. Yet such an outcome is not due to my choosing for a departure, but just to the necessity of finding a style that better suited the genre and storytelling specificities.

Concerning the elements of continuity, I would say that irony is still present. With the word irony I refer to the ironic aspect of life that everyone experiences, and I myself experience as well. The ironic nature of life to me also comprises the problems and accidents engendered by the lack of communication between people. For example, in The Quiet Family the ironic aspect is displayed through the fact that everything goes the opposite way from what the title family desires. In The Foul King (2000) a shy and peaceful bank teller ends up becoming a wrestling sensation, and this is ironic in itself. In Two Sisters the tragic irony is represented by the fact that those memories that one would like to forget the most stick instead to the conscience like a ghost, and you really cannot get rid of them.

Concerning the elements of continuity, I would say that irony is still present. With the word irony I refer to the ironic aspect of life that everyone experiences, and I myself experience as well. The ironic nature of life to me also comprises the problems and accidents engendered by the lack of communication between people. For example, in The Quiet Family the ironic aspect is displayed through the fact that everything goes the opposite way from what the title family desires. In The Foul King (2000) a shy and peaceful bank teller ends up becoming a wrestling sensation, and this is ironic in itself. In Two Sisters the tragic irony is represented by the fact that those memories that one would like to forget the most stick instead to the conscience like a ghost, and you really cannot get rid of them.

In A Bittersweet Life a very bad reversal of fortune occurs to the protagonist. He then starts looking for the reasons behind it in external factors, eventually setting out for vengeance. In the end, only after he accomplishes his vengeance, he realizes that the real reason for his misfortune was right inside himself. Unfortunately he comes to understand that only when close to death, and this represents a very tragic irony. At the core of Bittersweet Life lies once again an example of lack of communication. In this case it is not just lack of communication between individuals, but between someone and his very self.

Regarding A Bittersweet Life, you have more than once stated that you were inspired and influenced by the works of French auteur Jean-Pierre Melville.

From Melville I think I have taken two things, one at the level of meaning, and the other at the level of expression. From the point of view of deeper meaning I think I have tried in this film to transpose into images the vanity of life, by taking a cynical and detached stance in exposing such vanity. At the level of expression, I borrowed the indirect, oblique manners of narrative in Melville. I tried to reproduce his ability to use gazes, the body language of actors, the sheer weight of atmosphere, the meaningful presence, absence and variation of light; all in all, his ability to speak without words.

The mise en scene in your films seems to reveal an utmost, almost obsessive, care for details, often resulting in stunning visual compositions. What is your approach to the conception of single sequences? Do you rely upon storyboards?

The mise en scene in your films seems to reveal an utmost, almost obsessive, care for details, often resulting in stunning visual compositions. What is your approach to the conception of single sequences? Do you rely upon storyboards?

Yes, I do use storyboards and I also work in close contact with my production designer. However, when it comes to the final visual presentation, the fashion of narrating on the screen, the result is all determined by my choices. In A Bittersweet Life this is especially true because I took great care and interest in all aspects of composition. For example, I myself have carefully designed and supervised all the choices related to the relationship between the character and space inside the frame, or all the choices related to the use of music.

Melville's declared influence aside, A Bittersweet Life displays some very recognizable visual quotes or references to other films.

I personally like very much the films of the Coen Brothers and of Quentin Tarantino because you can see that they willingly include quotes and references to other directors and other films.

The overall visual style of the film is of course indebted to Melville, yet in sequences of action, I would say that my main references were Kill Bill or Scarface, especially for the final gunfight.

What can you say about the emblematic composition where Sun-woo and his boss face each other in front of the writing La Dolce Vita ? [A reference to Federico Fellini's classic, winner of Cannes' Palme d'Or in 1960 -- the title translates in English as The Sweet Life, just as Dalkomhan Insaeng, the original Korean title of A Bittersweet Life]

What can you say about the emblematic composition where Sun-woo and his boss face each other in front of the writing La Dolce Vita ? [A reference to Federico Fellini's classic, winner of Cannes' Palme d'Or in 1960 -- the title translates in English as The Sweet Life, just as Dalkomhan Insaeng, the original Korean title of A Bittersweet Life]

It is clearly intended as an ironic touch. It is a blatant irony that in between these two people, who are perhaps at the most dramatic and unfortunate point in their lives, there stands writing saying La Dolce Vita or the sweet life. Of course, life is not sweet at all, and the effect created by the juxtaposition of the characters and the writing in this peculiar situation is one of distancing, perhaps of cynicism highlighting the incongruity.

There is a big paradox lying behind the narrative curve of A Bittersweet Life. Not only does Sun-woo never consummate his love for Hee-soo, he never even pronounces it! Yet, he undergoes a disproportionate punishment, facing tremendous consequences for something that only stayed within his mind.

The character of Sun-woo is a mirror reflection of what really happens in life. Sometimes you suffer from love pains, and eventually discover that you lost your love just because of some small, silly reason. It often happens in life that big tragedies originate in something really small. Most people tend to look for explanations only in bigger, visible events, while overlooking smaller, apparently insignificant happenings. To counter this common sense I have intentionally conceived a character who experiences a tragic fate just because of a small mistake.

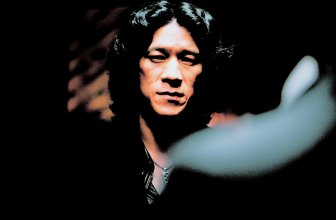

In A Bittersweet Life I also wanted to talk about love, love that remains unexpressed, love that looks and suffers in silence. This depiction of love is reminiscent of a quote from Jacques Derrida saying that even the love that only looks suffers. In order to effectively portray a character loving from afar and never expressing his innermost feelings, I needed an actor capable of expressing himself through small details, leaving most on the inside, and that is why I cast Lee Byung-hun and relied a lot on his performance.

In its second half, A Bittersweet Life veers into a chronicle of vengeance. This motif of vengeance has been at the centre of a much discussed trilogy by Park Chan-wook. Do you think there are differences in the approach to this theme between Park's films and yours?

In its second half, A Bittersweet Life veers into a chronicle of vengeance. This motif of vengeance has been at the centre of a much discussed trilogy by Park Chan-wook. Do you think there are differences in the approach to this theme between Park's films and yours?

In Park Chan-wook's Sympathy for Lady Vengeance the protagonist is able to accomplish her vengeance and thus experiences some sort of catharsis. In my film too the protagonist accomplishes his vengeance. Yet, this process is voided of any consequence since, as soon as he brings the vengeance to completion, the avenger himself dies. Vengeance thus proves to be useless. The main point here is that, while pursuing his vengeance, Sun-woo realizes that his real problem was inside himself. The pursuit of vengeance is eventually instrumental to this process of self-awakening, a tool to understand the truth about oneself.

What can you say about the two Buddhist parables opening and closing the film?

As for the one at the beginning, I intended to open A Bittersweet Life with some narration in voice over. I thought this parable on the wind and the tree could perfectly fit with the main theme of the film, so I chose it. The one at the ending came up as a perfect conclusion while making the film. I mean that it was not meant to be there from the beginning; it just came up as the perfect answer to the questions I was asking myself when I started the film.

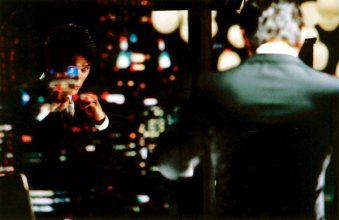

What about the very final shot, where Lee Byung-hun boxes against his own reflection?

What about the very final shot, where Lee Byung-hun boxes against his own reflection?

That is the key sequence expressing the essence of the character. It is an effective manner of projecting the character's inner self to the exterior. Sun-woo is a character whose idea of himself is entirely determined by the ideas others have of him. He thinks of himself only as reflected in other people's view of him, and he believes to be like that. He is a character who has never questioned himself before.

In the last scene, when Sun-woo boxes against his reflection, I wanted to convey the idea that, in the battle against himself, he lost. If you look carefully at the ending, you will notice that his reflection disappears first, leaving only the glass and outside panorama before the credits.

Paolo Bertolin, FLORENCE March 2005